Maquis (World War II)

Central Europe Germany Italy Spain (Spanish Civil War) Albania Austria Baltic states Belgium Bulgaria Burma China Czechia Denmark France Germany Greece Italy Japan Jewish Luxembourg Netherlands Norway Poland Romania Slovakia Spain Soviet Union Yugoslavia Germany Italy Netherlands Portugal Spain Sweden Switzerland United Kingdom United States The Maquis (French pronunciation: [maˈki] ⓘ) were rural guerrilla bands of French and Belgian Resistance fighters, called maquisards, during World War II.

[3] Originally the word came from the kind of terrain in which the armed resistance groups hid, high ground in southeastern France covered with scrub growth called maquis (scrubland).

In reaction to their weakening power, the occupiers and Vichy collaborationists began a terror campaign throughout France, enacted by German military units and the Milice.

[8] This included reprisals by SS troops against civilians living in areas where the French resistance was active, such as the Oradour-sur-Glane, the Maillé and the Tulle massacres.

[7] In French Indochina, the local resistance fighting the Japanese since 1941 was backed up by a special forces airborne commando unit created by de Gaulle in 1943, and known as the Corps Léger d'Intervention (CLI).

In 1944, an OSS agent, Robert R. Kehoe, was embedded within a group of Maquis and described the organization as "fractured",[10] observing that "the various components were quite independent, with members loyal to their own leaders and to the political forces behind them".

[11] People like Georges Loustaunau-Lacau and Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, leaders of the French Resistance group Alliance, were both questioned about their loyalty during and after the war.

For example, Maquis groups in Brittany often did not speak French and were focused on the expulsion of German forces from their region and not from France as a whole.

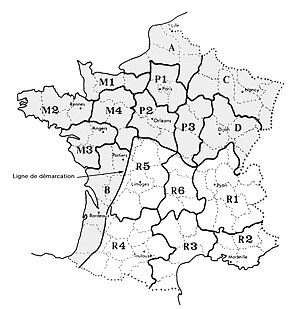

[citation needed] Prior to the inception of the Maquis, small resistance groups were created in the occupied and unoccupied zones of France.

In northern and western France, movements like Organisation civile et militaire, Libération-Nord, Ceux de la Libération, Ceux de la Résistance survived through clandestine pamphlets or newspapers, to build up a solidarity of attitudes and disparate actions and to 'taunt the Germans' (narguer les Allemands).

[15] It required young men born between 1920 and 1922 to register at their mairies (town halls), whereupon the authorities "listed several categories of workers, divided them into those who were exempt, those who would be liable for compulsory service in Germany, and those who would have to work for German industries in France".

[16] These first few months of refusal of STO, and the "embryonic camps and groupings that resulted" contributed to the eventual emergence of the mystique and discourse of le maquis.

[19] This unification was due, in part, to Michel Brault, a Parisian lawyer, who headed the organization of the resisters in April 1943, and to the drafted circulars establishing the Maquis's charter.

[19] Brault, in a report sent to London on 14 February 1944, listed the various elements available for action to the Allies and described the Maquis as "youths who have rebelled against the STO as well as men of all ages who have given up trying to live a normal life [...].

[21] The enemy would not be able to surprise the Maquis because the views from the mountains were extensive, but some enjoyed this advantage and stayed in the same sites for months, defying their own rules of mobility.

Guerrilla warfare practised by the Maquis "created a psychosis of fear within the enemy [...], giving an impression of numbers and strength which was more illusory than real".

As Allied troops advanced, the French Resistance rose against the Nazi occupation forces and their garrisons en masse.

[citation needed] When General De Gaulle dismissed resistance organizations after the liberation of Paris, many maquisards returned to their homes though many also joined the new French army.

Although the Maquis used whatever arms they could get, the groups affiliated with the Free French relied heavily on airdrops of weapons and explosives from the British SOE.

[24] SOE parachuted agents in with wireless sets (for radio communication) and dropped containers with various munitions including Sten guns, pencil detonators, plastic explosives, Welrod pistols (a silenced specialized assassination weapon favored by covert operatives) and assorted small arms such as pistols, rifles and sub-machine guns.

In leadership and the more technical aspects of leading a resistance group women were often more involved in the Maquis than men, helping the front line fighters.

[10] Lack of centralization led to groups taking action to garner attention so that more members would join and they would receive more supplies from the Allied war effort.