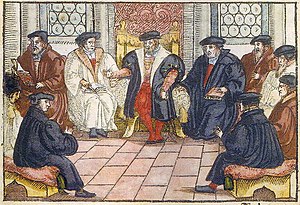

Marburg Colloquy

After the Diet of Speyer had confirmed the edict of Worms, Philip I felt the need to reconcile the diverging views of Martin Luther and Ulrich Zwingli in order to develop a unified Protestant theology.

The meeting ultimately failed to unify the Protestant movement, with Luther and Zwingli being unable to come to an agreement as to whether or not Christ's body and blood are present in the Eucharist.

Timothy George, an author and professor of Church History, summarized the incompatible views, "On this issue, they parted without having reached an agreement.

Indeed, to press the literal meaning of the text even farther, it follows that Christ would have again to suffer pain, as his body was broken again—this time by the teeth of communicants.

The same motive that had moved Zwingli so strongly to oppose images, the invocation of saints, and baptismal regeneration was present also in the struggle over the Supper: the fear of idolatry.

[4] Near the end of the colloquy when it was clear an agreement would not be reached, Philipp asked Luther to draft a list of doctrines that both sides agreed upon.

And although we have not been able to agree at this time, whether the true body and blood of Christ are corporally present in the bread and wine [of communion], each party should display towards the other Christian love, as far as each respective conscience allows, and both should persistently ask God the Almighty for guidance so that through his Spirit he might bring us to a proper understanding.The failure to find agreement resulted in strong emotions on both sides.

[8] At the later Diet of Augsburg, the Zwinglians and Lutherans again explored the same territory as that covered in the Marburg Colloquy and presented separate statements which showed the differences in opinion.