Marcus Garvey

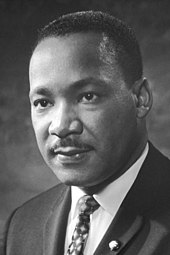

His black separatist views—and his relationship with white racists like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in the interest of advancing their shared goal of racial separatism—caused a division between Garvey and other prominent African-American civil rights activists such as W. E. B.

Some in the African diasporic community regarded him as a pretentious demagogue, and were highly critical of his collaboration with white supremacists, his violent rhetoric, and his prejudice against mixed-race people and Jews.

[39] In mid-1910, Garvey travelled to Costa Rica, where an uncle had secured him employment as a timekeeper on a large banana plantation in the Limón Province owned by the United Fruit Company (UFC).

[69] It portrayed itself not as a political organization but as a charitable club,[77] focused on work to help the poor and to ultimately establish a vocational training college modelled on Washington's Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

[82] In August 1914, Garvey attended a meeting of the Queen Street Baptist Literary and Debating Society, where he met Amy Ashwood, recently graduated from the Westwood Training College for Women.

[88] Many also felt that he was unnecessarily derogatory when describing black Jamaicans, with letters of complaint being sent into the Daily Chronicle after it published one of Garvey's speeches in which he referred to many of his people as "uncouth and vulgar".

[136] The government feared that African Americans would be encouraged toward revolutionary behavior following the October Revolution in Russia,[137] and in this context, military intelligence ordered Major Walter Loving to investigate Garvey.

The NAACP focused its attention on what it termed the "talented tenth" of the African-American population, such as doctors, lawyers, and teachers, whereas UNIA included many poorer people and Afro-Caribbean migrants in its ranks, seeking to project an image of itself as a mass organization.

[153] With an increased income coming in through UNIA, Garvey moved to a new residence at 238 West 131st Street;[143] in 1919, a young middle-class Jamaican migrant, Amy Jacques, became his personal secretary.

[154] UNIA also obtained a partly-constructed church building at 114 West 138 Street in Harlem, which Garvey named "Liberty Hall" after its namesake in Dublin, Ireland, which had been established during the Easter Rising of 1916.

[169] At the conference, UNIA delegates declared Garvey to be the Provisional President of Africa, charged with heading a government-in-exile that could take power in the continent when European colonial rule ended via decolonization.

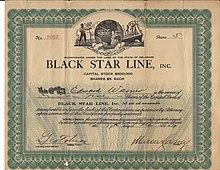

[199] He thought that the project could be launched by raising $2 million from African-American donors,[200] publicly declaring that any black person who did not buy stock in the company "will be worse than a traitor to the cause of struggling Ethiopia".

[259] Following the murder, eight prominent African Americans signed a public letter calling Garvey "an unscrupulous demagogue who has ceaselessly and assiduously sought to spread among Negroes distrust and hatred of all white people".

[290] Later examination suggested that, despite King's assurances to the UNIA team, the Liberian government had never seriously intended to allow African-American colonization, aware that it would harm relations with the British and French colonies on their borders, who feared the political tensions it could bring with it.

[294] Writing for the unanimous court, judge Charles Merrill Hough opined: "It may be true that Garvey fancied himself a Moses, if not a Messiah; that he deemed himself a man with a message to deliver, and believed that he needed ships for the deliverance of his people; but with this assumed, it remains true that if his gospel consisted in part of exhortations to buy worthless stock, accompanied by deceivingly false statements as to the worth thereof, he was guilty of a scheme or artifice to defraud, if the jury found the necessary intent about his stock scheme, no matter how uplifting, philanthropic, or altruistic his larger outlook may have been.

[336] In September 1929 he addressed a crowd of 1,500 supporters, launching the PPP's manifesto, which included land reform to benefit tenant farmers, the addition of a minimum wage to the constitution, pledges to build Jamaica's first university and opera house, and a proposed law to impeach and imprison corrupt judges.

According to Grant, while he was living in London, Garvey displayed "an amazing capacity to absorb political tracts, theories of social engineering, African history and the Western Enlightenment.

[377] In July 1919 he stated that "the time has come for the Negro race to offer up its martyrs upon the altar of liberty even as the Irish [had] given a long list from Robert Emmet to Roger Casement.

[381] In Garvey's view, "no race in the world is so just as to give others, for the asking, a square deal in things economic, political and social", but rather each racial group will favor its own interests,[382] rejecting the "melting pot" notion of much 20th century American nationalism.

[397][385] Garvey was willing to collaborate with the KKK in order to achieve his aims, and it was willing to work with him because his approach effectively acknowledged its belief that the U.S. should only be a country for white people and campaigns for advanced rights for African Americans who are living within the U.S. should be abandoned.

[398] Garvey called for collaboration between black and white separatists, stating that they shared common goals: "the purification of the races, their autonomous separation and the unbridled freedom of self-development and self-expression.

[404] While he was imprisoned, he penned an editorial for the Negro World titled "African Fundamentalism", in which he called for "the founding of a racial empire whose only natural, spiritual and political aims shall be God and Africa, at home and abroad.

[398] A proponent of the Back-to-Africa movement, Garvey called for a vanguard of educated and skilled African Americans to travel to West Africa, a journey which would be facilitated by his Black Star Line.

[391] According to the scholar of African-American studies Wilson S. Moses, the future African state which Garvey envisioned was "authoritarian, elitist, collectivist, racist, and capitalistic",[391] suggesting that it would have resembled the later Haitian government of François Duvalier.

Garvey believed in economic independence for the African diaspora and through the UNIA, he attempted to achieve it by forming ventures like the Black Star Line and the Negro Factories Corporation.

"[165] He admired Booker T. Washington's economic endeavours but criticized his focus on individualism: Garvey believed that African-American interests would best be advanced if businesses included collective decision-making and group profit-sharing.

[433] He stated that communism was "a dangerous theory of economic or political reformation because it seeks to put government in the hands of an ignorant white mass who have not been able to destroy their natural prejudices towards Negroes and other non-white people.

[454] Garvey enjoyed dressing up in military costumes,[455] and he also adored regal pomp and ceremony;[421] he believed that pageantry would stir the black masses out of their apathy, despite the accusations of buffoonery which were made by members of the African-American intelligentsia.

[482] During his lifetime, some African Americans wondered if he really understood the racial issues which were present in U.S. society because he was a foreigner,[483] and later African-American leaders frequently held the view that Garvey had failed to adequately address anti-black racism in his thought.

[492] Chapman believed that both "Garveyism and multicultural education share the desire to see students of color learning and achieving academic success",[493] and both allotted significant attention to generating racial pride.