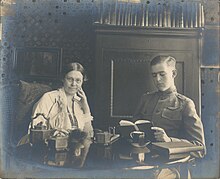

Margaret Eliza Maltby

1891 Margaret Eliza Maltby (December 10, 1860 – May 3, 1944) was an American physicist notable for her measurement of high electrolytic resistances and the conductivity of very dilute solutions.

Unusually for her time, she was able to continue her career in academia by keeping the birth a secret and later claiming the child publicly through adoption.

[9][10] Following college Maltby studied at the Art Students League of New York and taught high school in Ohio for four years.

[3] While at MIT, Maltby conducted research on acoustics with Charles R. Cross on the minimum number of vibrations necessary to determine a difference in frequency between two sounds.

Their research was in response to work by Félix Savart and Friedrich Kohlrausch who had argued that at least two cycles of a sound wave were required.

This fellowship, created largely through the efforts of Christine Ladd-Franklin, was intended to pressure foreign universities to open their doors to female students on a regular basis.

[4][failed verification] For her doctoral work Maltby studied under Walther Nernst in his physical chemistry laboratory.

Nernst was interested in the theory of ionic dissociation and early research into this topic had focused on solutions that were relatively good conductors.

[16] After she received her doctorate she worked at the newly founded Institut für Physikalische Chemie at Göttingen under Nernst.

[17][18][19] When she returned from Germany in 1896, Maltby took up a position as associate professor at Wellesley College where she substituted for Sarah Frances Whiting who was on sabbatical.

Maltby resumed her teaching career as an instructor at Lake Erie College in September 1897 where she substituted for Mary Chilton Noyes.

Maltby's involvement in administration and building up the physics department left her little time for research, although she spent a sabbatical year from 1909–1910 at the Cavendish Laboratory.

[6] While at Barnard, Maltby took an active role in college life, including participating in student groups, judging contests, and hosting afternoon teas for the faculty.

"[21] Although Maltby supported the ability of other female academics to marry, she personally did not believe that marriage would be beneficial between two scientists.

She wrote to Svante Arrhenius on the occasion of his divorce that she believed that it was inevitable that one personality would subsume the other in a marriage of two scientists, and so she herself never wanted to get married.

Although Brooks assumed she would be able to keep her position, Laura Gill, the Dean of Barnard College at the time, was strongly opposed.

Gill likely viewed marriage as a form of disloyalty by a female instructor to the college, in contrast to motherhood which was an appoved role.

[21] In 2014, Autosomal DNA tests of Meyer's two daughters through Ancestry.com showed strong links to known descendants of Maltby's mother and of her father.