Maria Theresa

She was the sovereign of Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, Transylvania, Slavonia, Mantua, Milan, Moravia, Galicia and Lodomeria, Dalmatia, the Austrian Netherlands, Carinthia, Carniola, Gorizia and Gradisca, Lusatia, Styria and Parma.

Frederick II of Prussia (who became Maria Theresa's greatest rival for most of her reign) promptly invaded and took the affluent Habsburg province of Silesia in the eight-year conflict known as the War of the Austrian Succession.

She promulgated institutional, financial, medical, and educational reforms, with the assistance of Wenzel Anton of Kaunitz-Rietberg, Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, and Gerard van Swieten.

The second and eldest surviving child of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI and Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Archduchess Maria Theresa was born on 13 May 1717 in Vienna, six months after the death of her elder brother, Archduke Leopold Johann,[1] and was baptised on that same evening.

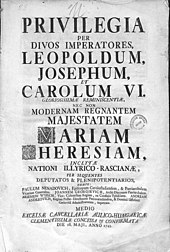

[3] It was clear that Maria Theresa would outrank them,[3] even though their grandfather, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, had his sons sign the Mutual Pact of Succession, which gave precedence to the daughters of the elder brother.

They exacted harsh terms: in the Treaty of Vienna (1731), Great Britain demanded that Austria abolish the Ostend Company in return for its recognition of the Pragmatic Sanction.

[6] In total, Great Britain, France, Saxony, United Provinces, Spain, Prussia, Russia, Denmark, Sardinia, Bavaria, and the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire recognised the sanction.

[18][19] Francis Stephen remained at the imperial court until 1729, when he ascended the throne of Lorraine,[17] but was not formally promised Maria Theresa's hand until 31 January 1736, during the War of the Polish Succession.

[20] Louis XV of France demanded that Maria Theresa's fiancé surrender his ancestral Duchy of Lorraine to accommodate his father-in-law, Stanisław I, who had been deposed as king of Poland.

Ten years later, Maria Theresa recalled in her Political Testament the circumstances under which she had ascended: "I found myself without money, without credit, without army, without experience and knowledge of my own and finally, also without any counsel because each one of them at first wanted to wait and see how things would develop.

[42] As Austria was short of experienced military commanders, Maria Theresa released Marshal Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg, who had been imprisoned by her father for his poor performance in the Turkish War.

"[54] However, she managed to show her gift for theatrical displays by holding her son and heir, Joseph, while weeping, and she dramatically consigned the future king to the defense of the "brave Hungarians".

[64] Prussia became anxious at Austrian advances on the Rhine frontier, and Frederick again invaded Bohemia, beginning a Second Silesian War; Prussian troops sacked Prague in August 1744.

[66] The wider war dragged on for another three years, with fighting in northern Italy and the Austrian Netherlands; however, the core Habsburg domains of Austria, Hungary and Bohemia remained in Maria Theresa's possession.

Thus, the efforts of Kaunitz and Starhemberg managed to pave a way for a Diplomatic Revolution; previously, France was one of Austria's archenemies together with Russia and the Ottoman Empire, but after the agreement, they were united by a common cause against Prussia.

In return, Austria would cede several towns in the Austrian Netherlands to the son-in-law of Louis XV, Philip of Parma, who in turn would grant his Italian duchies to Maria Theresa.

[73] After the defeat in Torgau on 3 November 1760, Maria Theresa realised that she could no longer reclaim Silesia without Russian support, which vanished after the death of Empress Elizabeth in early 1762.

[73] Although Silesia remained under the control of Prussia, a new balance of power was created in Europe, and Austrian position was strengthened by it thanks to its alliance with the Bourbons in Madrid, Parma and Naples.

Maria Theresa blamed herself for her daughter's death for the rest of her life because, at the time, the concept of an extended incubation period was largely unknown and it was believed that Josepha had caught smallpox from the body of the late empress.

[113] She employed Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, who modernised the empire by creating a standing army of 108,000 men, paid for with 14 million florins extracted from crown lands.

[122] After Maria Theresa recruited Gerard van Swieten from the Netherlands, he also employed a fellow Dutchman named Anton de Haen, who founded the Viennese Medicine School (Wiener Medizinische Schule).

Stollberg-Rilinger notes that the reform of the primary schools in particular was the most long-lasting success of Maria Theresa's later reign, and one of the few policy agendas in which she was not in open conflict with her son and nominal co-ruler Joseph II.

Maria Theresa thereupon wrote to her rival Frederick II of Prussia to request him to allow the Silesian school reformer Johann Ignaz von Felbiger to move to Austria.

[139] Austrian historian Karl Vocelka observed that the educational reforms enacted by Maria Theresa were "really founded on Enlightenment ideas," although the ulterior motive was still to "meet the needs of an absolutist state, as an increasingly sophisticated and complicated society and economy required new administrators, officers, diplomats and specialists in virtually every area.

Although Maria Theresa had initially been reluctant to meddle in such affairs, government interventions were made possible by the perceived need for economic power and the emergence of a functioning bureaucracy.

[149] The census of 1770–1771 gave the peasants opportunity to express their grievances directly to the royal commissioners and made evident to Maria Theresa the extent to which their poverty was the result of the extreme demands for forced labour (called "robota" in Czech) by the landlords.

In 1773, she entrusted her minister Franz Anton von Raab with a model project on the crown lands in Bohemia: he was tasked to divide up the large estates into small farms, convert the forced labour contracts into leases, and enable the farmers to pass the leaseholds onto their children.

[180] Maria Theresa understood the importance of her public persona and was able to simultaneously evoke both esteem and affection in her subjects; a notable example was how she projected dignity and simplicity to awe the people in Pressburg before she was crowned as Queen (Regnant) of Hungary.

[182] She centralised and modernised its institutions, and her reign was considered as the beginning of the era of "enlightened absolutism" in Austria, with a brand new approach toward governing: the measures undertaken by rulers became more modern and rational, and thoughts were given to the welfare of the state and the people.

"[185] Despite being among the most successful Habsburg monarchs and remarkable leaders of the 18th century, Maria Theresa has not captured the interest of contemporary historians or media, perhaps due her hardened nature.