Mariano Moreno

He wrote a thesis with strong criticism of the native slavery at the mines of Potosí, influenced by the Spanish jurist Juan de Solorzano Pereira,[6] the foremost publisher of Indian Law, and Victoria Villalva, fiscal of the Audiencia of Charcas and defender of the indigenous cause.

Unlike the criollo politicians Manuel Belgrano and Juan José Castelli, he did not support viceroy Liniers or the Carlotist project, which sought the coronation of Carlota of Spain in the Americas.

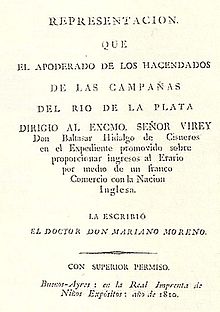

Cisneros allowed free trade as well, as instructed by the Junta of Seville, which benefited British merchants; Britain was allied with Spain in the Peninsular War.

The agents of the Consulate of Cadiz asserted that this would hurt the local economy, moral values, social usages, religious practices, and the loyalty to Spain and its monarchy.

Several authors have questioned Moreno's authorship of the paper, considering it instead an update of another, previously drafted by Manuel Belgrano, Secretary of the Commerce Consulate of Buenos Aires, written to make a similar request to the former viceroy Liniers.

He attended the May 22 open Cabildo, but according to the father of Vicente Fidel López and the father-in-law of Bartolomé Mitre (both direct witness) he stayed silent at one side and did not join the debate.

[22] The Junta faced strong opposition from the beginning: it was resisted locally by the Cabildo and the Royal Audiencia, still loyal to the absolutist factions; the nearby plazas of Montevideo and Paraguay did not recognize it, and Santiago de Liniers organized a counter-revolution at Córdoba.

He was supported by the popular leaders Domingo French and Antonio Beruti, Dupuy, Donado, Orma, and Cardozo; and priests like Grela and Aparicio.

[23] Historian Carlos Ibarguren described that Morenist youths roamed the streets preaching new ideas to each pedestrian they found, turned the "Marcos" coffee shop into a political hall, and proposed that all social classes should be illustrated.

[29] In reference to the Courts of Cádiz that would write a Constitution, he said that the Congress "may establish an absolute disposal of our beloved Ferdinand",[30] meaning that the right of self-determination would allow even that.

[43] When the counter-revolution became stronger Moreno called the Junta and, with support from Castelli and Paso, proposed that the enemy leaders should be shot as soon as they were captured instead of brought to trial.

Moreno gave harsh new instructions for it; namely: The context was not favorable: only Cochabamba and Charcas made a genuine support of the revolution, and some indigenous people hesitated in joining, fearing the consequences of a possible royalist counter-attack.

[50] The Morenist projects for Upper Peru, which included the emancipation of the indigenous peoples and the nationalization of the mines of Potosi, were resisted by the local populations that were benefiting from the system already in force.

He gave them full civil and political rights, granted lands, authorized commerce with the United Provinces, removed taxes for ten years, abolished any type of torture, and lifted restrictions on taking public or religious office.

[60] Manuel Andrés Arroyo y Pinedo, another rich man, blamed Moreno for these actions, accusing him of equaling disagreement with anti-patriotism, and felt that the ideas of egalitarianism would only cause great evils.

[61] Those measures were also criticized by moderate supporters of the revolution, such as Gregorio Funes from Córdoba, who rejected the lack of proper trials,[62] or Dámaso Uriburu, from Salta, who compared Moreno, Castelli, and Vieytes with the French Jacobins.

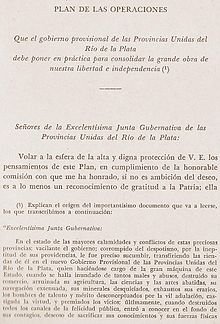

[67] The document states the need to defeat the royalist forces and therefore proposes many possible actions similar to those employed by Jacobins during the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution.

He proposed to distribute large numbers of Gazeta de Buenos Ayres newspapers, filled with libertarian ideas and translated into Portuguese,[75][76] and provide military support to the slaves if they should riot.

He considered the risk of a complete Spanish defeat in the Peninsular War or a restoration of absolutism great menaces and regarded Britain as a potential ally against them.

[citation needed] Mariano Moreno and Cornelio Saavedra had disagreements about the events of the May Revolution and the way to run the government; their disputes became public shortly after the creation of the Junta.

[99] Saavedra increased his resistance to Moreno's proposals after the victory at the Battle of Suipacha, considering that the revolution had defeated its enemies and should relax its severity in consequence.

[106][107] The Brazilian government sent Carlos José Guezzi to Buenos Aires, with the purpose of mediating in the conflict with the royalists at Montevideo and to ratify the aspirations of Carlota Joaquina to rule as regent.

His opposition to the incorporation of the deputies is seen by some historians as an initial step in the conflict between Buenos Aires and the other provinces, which dominated politics in Argentina during the following decades.

His health declined and there was no doctor on board, but the captain refused requests to sail into some ports which were positioned along the route such as in Rio de Janeiro or Cape Town.

Further points used to sustain the idea of a murder are the captain's refusal to land elsewhere, his slow sailing, his administration of the emetic in secrecy, and that he didn't return to Buenos Aires with the ship.

The son of Mariano Moreno commented to the historian Adolfo Saldías that his mother, Guadalupe Cuenca, received an anonymous gift of a mourning hand fan and handkerchief, with instructions to use them soon.

The military defeats of Castelli and Belgrano started a new political crisis, and the First Triumvirate replaced the Junta Grande as the executive power, and then closed it completely.

According to those authors, Moreno was in the employ of the British, a demagogic caudillo, a paranoid, a mere man of theoretical ideas applying European principles that failed in the local context, wrongly portrayed as the leader of the Revolution by the liberal historiography.

[132] The harsh policies are acknowledged, but not attributed specifically to Moreno, but rather to the whole Junta, and compared with similar royalist measures used to punish the Chuquisaca, the La Paz revolution, and the indigenous rebellion of Túpac Amaru II.

Carranza belonged to the mainstream line of historians who professed great admiration for Moreno, who he described as follows: "He was the soul of the government of the revolution of May, his nerve, the distinguished statesman of the group managing the ship attacked the absolutism and doubt, anxious to reach the goal of his aspirations and his destiny.