Marine geophysics

Objectives of marine geophysics include determination of the depth and features of the seafloor, the seismic structure and earthquakes in the ocean basins, the mapping of gravity and magnetic anomalies over the basins and margins, the determination of heat flow through the seafloor, and electrical properties of the ocean crust and Earth's mantle.

The depth of the seafloor is measured using echo sounding, a sonar method developed during the 20th century and advanced during World War II.

When the sound or energy source is separated from the recording devices by distances of several kilometers or more, then refracted seismic waves are measured.

[6] Gravimeters using the zero-length spring technology are mounted in the most stable location on a ship; usually towards the center and low.

[7] The geothermal gradient is measured using a 2-meter long temperature probe or with thermistors attached to sediment core barrels.

[17] Data from marine seismic refraction experiments defined a thin ocean crust, approximately 6 to 8 kilometers in thickness, divided into three layers.

[21] Correlation of the anomalies to the history of Earth's magnetic field reversals allowed the age of the seafloor to be estimated.

[29][30] Swath sonar mapping has revealed the gouge tracks of ice sheets cut as they traversed polar continental shelves in the past.

[26][25] On the ridge crest, however, conductive heat flow was found to be unexpectedly low for a location where active volcanism accompanies seafloor spreading.

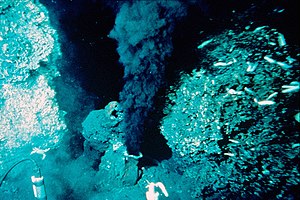

[32] This anomaly was explained by the possible heat transfer by hydrothermal venting of seawater circulating in deep fissures in the crust at the ridge crest spreading centers.

This hypothesis was borne out in the late 20th century when investigations by deep submersibles discovered hydrothermal vents at spreading centers.