Mariner 2

Original plans called for the probes to be launched on the Atlas-Centaur, but serious developmental problems with that vehicle forced a switch to the much smaller Agena B second stage.

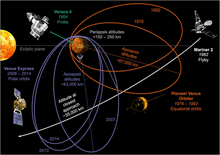

The Mariner 2 spacecraft was launched from Cape Canaveral on August 27, 1962, and passed as close as 34,773 kilometers (21,607 mi) to Venus on December 14, 1962.

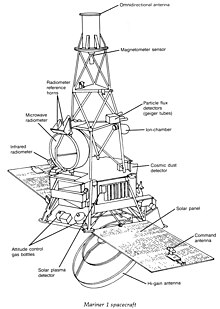

[4] The Mariner probe consisted of a 100 cm (39.4 in) diameter hexagonal bus, to which solar panels, instrument booms, and antennas were attached.

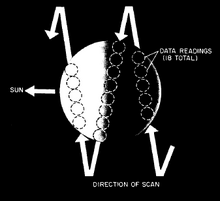

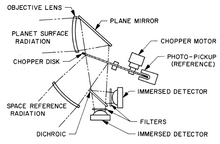

The primary mission was to receive communications from the spacecraft in the vicinity of Venus and to perform radiometric temperature measurements of the planet.

With the advent of the Cold War, the two then-superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, both initiated ambitious space programs with the intent of demonstrating military, technological, and political dominance.

The Americans followed suit with Explorer 1 on February 1, 1958, by which point the Soviets had already launched the first orbiting animal, Laika in Sputnik 2.

A plan drafted January 1959 involved two spacecraft evolved from the first Pioneer probes, one to be launched via Thor-Able rocket, the other via the yet-untested Atlas-Able.

The Thor-Able probe was repurposed as the deep space explorer Pioneer 5, which was launched March 11, 1960, and designed to maintain communications with Earth up to a distance of 20,000,000 mi (32,000,000 km) as it traveled toward the orbit of Venus.

NASA accepted the proposal, and JPL began an 11-month crash program to develop "Mariner R" (so named because it was a Ranger derivative).

The main body of the craft was hexagonal with six separate cases of electronic and electromechanical equipment: At the rear of the spacecraft, a monopropellant (anhydrous hydrazine) 225 N[17] rocket motor was mounted for course corrections.

[9]: 175–176 Temperature control was both passive, involving insulated, and highly reflective components; and active, incorporating louvers to protect the case carrying the onboard computer.

The planet's rotation rate was uncertain, though JPL scientists had concluded through radar observation that Venus rotated very slowly compared to the Earth, advancing the long-standing[18] (but later disproven[19]) hypothesis that the planet was tidally locked with respect to the Sun (as the Moon is with respect to the Earth).

[16]: 331 An on-board magnetometer and suite of charged particle detectors could determine if Venus possessed an appreciable magnetic field and an analog to Earth's Van Allen Belts.

[21] As the Mariner spacecraft would spend most of its journey to Venus in interplanetary space, the mission also offered an opportunity for long-term measurement of the solar wind of charged particles and to map the variations in the Sun's magnetosphere.

The cosmic dust detector and solar plasma spectrometer were attached to the top edges of the spacecraft base.

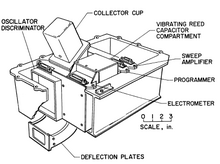

The DCS was a solid-state electronic system designed to gather information from the scientific instruments on board the spacecraft.

With payload space at a premium, project scientists considered a camera an unneeded luxury, unable to return useful scientific results.

Carl Sagan, one of the Mariner R scientists, unsuccessfully fought for their inclusion, noting that not only might there be breaks in Venus' cloud layer, but "that cameras could also answer questions that we were way too dumb to even pose".

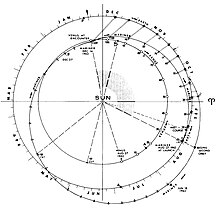

[30] The launch window for Mariner, constrained both by the orbital relationship of Earth and Venus and the limitations of the Atlas Agena, was determined to fall in the 51-day period from July 22 through September 10.

[9]: 174 The Mariner flight plan was such that the two operational spacecraft would be launched toward Venus in a 30-day period within this window, taking slightly differing paths such that they both arrived at the target planet within nine days of each other, between the December 8 and 16.

Deep space support was provided by three tracking and communications stations at Goldstone, California, Woomera, Australia, and Johannesburg, South Africa, each separated on the globe by around 120° for continuous coverage.

[16]: 231–233 On July 22, 1962, the two-stage Atlas-Agena rocket carrying Mariner 1 veered off-course during its launch due to a defective signal from the Atlas and a bug in the program equations of the ground-based guidance computer; the spacecraft was destroyed by the Range Safety Officer.

The Atlas proved troublesome to prepare for launch, and multiple serious problems with the autopilot occurred, including a complete replacement of the servoamplifier after it had suffered component damage due to shorted transistors.

The vernier started oscillating and banging against its stops, resulting in a rapid roll of the launch vehicle that came close to threatening the integrity of the stack.

The incident was traced to a loose electrical connection in the vernier feedback transducer, which was pushed back into place by the centrifugal force of the roll, which also by fortunate coincidence left the Atlas only a few degrees off from where it started and within the range of the Agena's horizontal sensor.

The NASA NDIF tracking station at Johannesburg, South Africa, acquired the spacecraft about 31 minutes after launch.

As all subsystems were performing normally, with the battery fully charged and the solar panels providing adequate power, the decision was made on August 29 to turn on cruise science experiments.

[16]: 114 Mariner 2 was the first spacecraft to successfully encounter another planet,[3] passing as close as 34,773 kilometers (21,607 mi) to Venus after 110 days of flight on December 14, 1962.

[16][44] It was also shown that in interplanetary space, the solar wind streams continuously,[32][45] confirming a prediction by Eugene Parker,[46] and the cosmic dust density is much lower than the near-Earth region.

Also, research, which was later confirmed by Earth-based radar and other explorations, suggested that Venus rotates very slowly and in a direction opposite that of the Earth.

Mariner 2 · Venus · Earth