Marriage in ancient Greece

Marriage in ancient Greece had less of a basis in personal relationships and more in social responsibility, however the available historical records on the subject focus exclusively on Athens or Sparta and primarily on the aristocratic class.

In keeping with this idea, the heroes of Homer never have more than one wife by law,[3] though they may be depicted with living with concubines, or having sexual relationships with one or more women.

In Plato's Laws, the would-be lawgiver suggests that any man who was not married by age 35 should be punished with a loss of civil rights and with financial consequences.

[4] In Ancient Sparta, the subordination of private interests and personal happiness to the good of the public was strongly encouraged by the laws of the city.

[5] These regulations were founded on the generally recognised principle that it was the duty of every citizen to raise up strong and healthy legitimate children to the state.

[8] On the same principle, and to prevent the end of the family line, Spartan King Anaxandridas II was allowed to live with two wives.

Though the code records the law, scholar Sue Blundell reminds us we should not assume that this reflects a consistently held practice.

A man would choose his wife based on three things: the dowry, which was given by the father of the bride to the groom; her presumed fertility; and her skills, such as weaving.

The exchange also showed that the girl's family was not simply selling her or rejecting her; the gifts formalized the legitimacy of a marriage.

[16] This practice was mainly confined to high status wealthy men, allowing them multiple concubines and mistresses but only one wife.

Plato mentions one of these as the duty incumbent upon every individual to provide for a continuance of representatives to succeed himself as ministers of the Divinity (toi Theoi hyperetas an' hautou paradidonai).

Another was the desire felt by almost everyone, not merely to perpetuate his own name, but also to prevent his heritage being desolate, and his name being cut off, and to leave someone who might make the customary offerings at his grave.

[20] However, proximity by blood (anchisteia), or consanguinity (syngeneia), was not, with few exceptions, a bar to marriage in any part of Greece; direct lineal descent was.

[21] Thus, brothers were permitted to marry even with sisters, if not homometrioi or born from the same mother, as Cimon did with Elpinice, though a connection of this sort appears to have been looked on with abhorrence.

[11] Under Solon's reforms couples of this nature were required to have sex a minimum of three times per month in order to conceive a male heir.

Moreover, if a father had not determined himself concerning his daughter, the king's court decided who among the privileged persons or members of the same family should marry the heiress.

The woman did not decide whom she would marry, only under very special circumstances, and she played no active role in the engysis process, which was not out of the norm for that time period.

It was made by the natural or legal guardian (kyrios) of the bride, usually her father, and attended by the relatives of both parties as witnesses.

It would seem, therefore, that the issue of a marriage without espousals would lose their heritable rights, which depended on their being born ex astes kai engyetes gynaikos, that is, from a citizen and a legally betrothed wife.

[34] Another custom peculiar to the Spartans, and a relic of ancient times, was the seizure of the bride by her intended husband (see Herodotus, vi.

[35] She was not, however, immediately domiciled in her husband's house, but cohabited with him for some time clandestinely, till he brought her, and frequently her mother also, to his home.

A similar custom appears to have prevailed in Crete, where, as we are told,[36] the young men when dismissed from the agela of their fellows were immediately married, but did not take their wives home till some time afterwards.

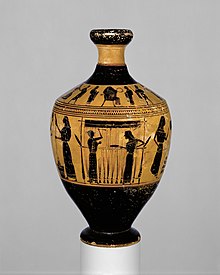

The proaulia was the time when the bride would spend her last days with her mother, female relatives, and friends preparing for her wedding.

This bath symbolized purification as well as fertility, and the water would have been delivered from a special location or type of container called the loutrophoros.

[12] The most important part was the marriage procession; a chariot driven by the groom bringing the still-veiled bride to his, and now her, home.

[11] Little is known about marriage ceremonies in ancient Gortyn, but some evidence suggests that brides may have been quite young, and would still live in their father's house until they could manage their husband's household.

Weaving and producing textiles were considered an incredibly important task for women, and they would often offer particularly fine works to the gods.

A husband would 'train' his wife to do this properly, as men could potentially be gone for long periods of time to deal with concerns of either democratic or military importance.

[2] Regardless of being married, Spartan men continued to live in the barracks until age thirty in times of both peace and war.

[2] The only goal of Spartan marriage was reproduction, and there were many cases of agreements being made for children to be conceived outside of just the husband and wife.