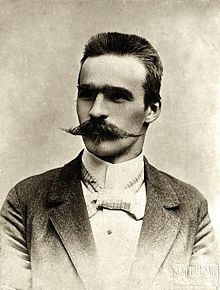

Józef Piłsudski

Although some aspects of Piłsudski's administration, such as imprisoning his political opponents at Bereza Kartuska, are controversial, he remains one of the most influential figures in Polish 20th-century history and is widely regarded as a founder of modern Poland.

[22] He was allowed to work in an occupation of his choosing and tutored local children in mathematics and foreign languages[7] (he knew French, German and Lithuanian in addition to Russian and his native Polish; he would later learn English).

[8][34] In the fall of 1904, Piłsudski formed a paramilitary unit (the Combat Organization of the Polish Socialist Party, or bojówki) aiming to create an armed resistance movement against the Russian authorities.

[43] In 1908, Piłsudski transformed his paramilitary units into a "Union of Active Struggle" (Związek Walki Czynnej, or ZWC), headed by three of his associates, Władysław Sikorski, Marian Kukiel and Kazimierz Sosnkowski.

[8][40] In 1914, while giving a lecture in Paris, Piłsudski declared, "Only the sword now carries any weight in the balance for the destiny of a nation", arguing that Polish independence can only be achieved through military struggle against the partitioning powers.

[16][49][56] In mid-1916, after the Battle of Kostiuchnówka, in which the Polish Legions delayed a Russian offensive at a cost of over 2,000 casualties,[57] Piłsudski demanded that the Central Powers issue a guarantee of independence for Poland.

[54] After the Russian Revolution in early 1917, and in view of the worsening situation of the Central Powers, Piłsudski took an increasingly uncompromising stance by insisting that his men no longer be treated as "German colonial troops" and be only used to fight Russia.

[60][61] In the aftermath of the July 1917 "oath crisis", when Piłsudski forbade Polish soldiers to swear loyalty to Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, he was arrested and imprisoned at Magdeburg.

The day after his arrival in Warsaw, he met with old colleagues from his time working with the underground resistance, who addressed him socialist-style as "Comrade" (Towarzysz) and asked for his support for their revolutionary policies.

[16][74] Piłsudski's plan met with opposition from most of the prospective member states, which refused to relinquish their independence, as well as the Allied powers, who thought it to be too bold a change to the existing balance-of-power structure.

[85] After the Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919, and a series of escalating battles that resulted in the Poles advancing eastward, on 21 April 1920, Marshal Piłsudski (as his rank had been since March 1920) signed a military alliance called the Treaty of Warsaw with Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura.

The most important role of the plan was assigned to a relatively small, approximately 20,000-man, newly assembled "Reserve Army" (also known as the "Strike Group", "Grupa Uderzeniowa"), comprising the most determined, battle-hardened Polish units that were commanded by Piłsudski.

Their task was to spearhead a lightning northward offensive, from the Vistula-Wieprz triangle south of Warsaw, through a weak spot that had been identified by Polish intelligence between the Soviet Western and Southwestern Fronts.

[87][96] Stanisław Stroński, a National Democrat Sejm deputy, coined the phrase "Miracle at the Vistula" (Cud nad Wisłą)[98] to express his disapproval of Piłsudski's "Ukrainian adventure".

[104] The treaty and his secret approval of General Lucjan Żeligowski's capture of Vilnius from the Lithuanians marked an end to this incarnation of Piłsudski's federalist Intermarium plan.

[110][44] Two days later, on 16 December 1922, Narutowicz was shot dead by a right-wing painter and art critic, Eligiusz Niewiadomski, who had originally wanted to kill Piłsudski but had changed his target, influenced by National Democrat anti-Narutowicz propaganda.

[116] Piłsudski criticized General Stanisław Szeptycki's proposal that the military should be supervised by civilians as an attempt to politicize the army, and on 28 June, he resigned his last political appointment.

[142][143] Many Jews saw Piłsudski as their only hope for restraining antisemitic currents in Poland and for maintaining public order; he was seen as a guarantor of stability and a friend of the Jewish people, who voted for him and actively participated in his political bloc.

Assisted by his protégé, Foreign Minister Józef Beck, he sought support for Poland in alliances with western powers, such as France and Britain, and with friendly neighbors such as Romania and Hungary.

[151][152][153] The Locarno treaties were intended by the British government to ensure a peaceful handover of the territories claimed by Germany such as the Sudetenland, the Polish Corridor, and the Free City of Danzig (modern Gdańsk, Poland) by improving Franco-German relations to such extent that France would dissolve its alliances in eastern Europe.

The Maginot line was a tacit French admission that Germany would be rearming beyond the limits set by the Treaty of Versailles in the near-future and that France intended to pursue a defensive strategy.

[158] In June 1932, just before the Lausanne Conference opened, Piłsudski heard reports that the new German chancellor Franz von Papen was about to make an offer for a Franco-German alliance to the French Premier Édouard Herriot which would be at the expense of Poland.

[159] Though the issue was ostensibly about access rights for the Polish Navy in Danzig, the real purpose of sending Wircher was as a way to warn Herriot not to disadvantage Poland in a deal with Papen.

[175][full citation needed] Condolences were officially expressed by senior clergy, including Pope Pius XI and August Cardinal Hlond, Primate of Poland.

[175] On the international scene, Pope Pius XI held a special ceremony on 18 May in the Holy See, a commemoration was conducted at League of Nations Geneva headquarters, and dozens of messages of condolence arrived in Poland from heads of state across the world, including Germany's Adolf Hitler, the Soviet Union's Joseph Stalin, Italy's Benito Mussolini and King Victor Emmanuel III, France's Albert Lebrun and Pierre-Étienne Flandin, Austria's Wilhelm Miklas, Japan's Emperor Hirohito, and Britain's King George V.[175] In Berlin, a service for Piłsudski was ordered by Adolf Hitler.

[181] Separate funeral ceremonies were held for the burial of his brain, which Piłsudski had willed for study to Stefan Batory University, and his heart, which was interred in his mother's grave at Vilnius's Rasos Cemetery.

After World War II, little of Piłsudski's political ideology influenced the policies of the Polish People's Republic, a de facto satellite of the Soviet Union.

This began to change after de-Stalinization and the Polish October in 1956, and historiography in Poland gradually moved away from a purely negative view of Piłsudski toward a more balanced and neutral assessment.

[193] On the sixtieth anniversary of his death on 12 May 1995, Poland's Sejm adopted a resolution: "Józef Piłsudski will remain, in our nation's memory, the founder of its independence and the victorious leader who fended off a foreign assault that threatened the whole of Europe and its civilization.

[105] c. ^ Polish Socialist Party – Revolutionary Faction from 1906 to 1909 Józef Piłsudski Ferdinand Foch Edward Rydz-Śmigły Michał Rola-Żymierski Konstanty Rokossowski Marian Spychalski