Martyrs' Day (Panama)

U.S. Army units became involved in suppressing the violence after Canal Zone police were overwhelmed, and after three days of fighting, about 22 Panamanians and four U.S. soldiers were killed.

The incident is considered to be a significant factor in the U.S. decision to transfer control of the Canal Zone to Panama through the 1977 Torrijos–Carter Treaties.

In addition, the United States Government purchased title to all the lands in the Canal Zone from the private owners.

According to Stephen Bosworth, the American Principal Officer in Colon, "there were several thousand families in the Canal Zone.

In fact, they were in this little American enclave, very well paid, lived very well, very generous fringe benefits and they recognized that as the Panamanians took control of the Canal that they would lose.

In response, the Zonians surrounded the flagpole, sang "The Star-Spangled Banner" and rejected the deal between the police and the Panamanian students.

In 1947, students from the Instituto Nacional had carried it in demonstrations opposing the Filos-Hines Treaty and demanding the withdrawal of U.S. military bases.

David M. White, an apprentice telephone technician with the Panama Canal Company, stated that "the police gripped the students, who were four or five abreast, under the shoulders in the armpits and edged them forward.

As word of the flag desecration incident spread, angry Panamanian crowds formed along and across the border between Panama City and the Canal Zone.

Meanwhile, demonstrators began to tear down the "Fence of Shame" located in the Canal Zone, a safety feature alongside a busy highway.

Some 80 to 85 police officers faced a hostile crowd of at least 5,000, and estimated by some sources to be 30,000 or more, all along and across the border between Panama City and the Canal Zone.

Some reporters alleged one giant communist plot, with Christian Democrats, Socialists, student government leaders and a host of others controlled by the hand of Fidel Castro.

However, it seems that Panama's communists were caught by surprise by the outbreak of violence and commanded the allegiance of only a small minority of those who rioted on the Day of the Martyrs.

A good indication of the relative communist strength came two weeks after the confrontations, when the Catholic Church sponsored a memorial rally for the fallen, which was attended by some 40,000 people.

A number of U.S. citizen residents of Panama City, particularly military personnel and their families who were unable to get housing on base, were forced to flee their homes.

Unlike in Panama City, Panamanian authorities in Colón had made early attempts to separate the combatants.

As the angry Panamanian mob turned their wrath against targets in Panama City, a number of people were shot to death under controversial circumstances.

A six-month-old girl, Maritza Ávila Alabarca, died with respiratory problems while her neighborhood was gassed by the U.S. Army with CS tear gas.

The 21 as listed there include: Maritza Ávila Alabarca, Ascanio Arosemena, Rodolfo Sánchez Benítez, Luis Bonilla, Alberto Constance, Gonzalo Crance, Teofilo De La Torre, José Del Cid, Victor Garibaldo, José Gil, Ezequiel González, Victor Iglesias, Rosa Landecho, Carlos Lara, Gustavo Lara, Ricardo Murgas, Estanislao Orobio, Jacinto Palacios, Ovidio Saldaña, Alberto Tejada and Celestino Villarreta.

Those who died on the American side include Staff Sergeant Luis Jimenez Cruz, Private David Haupt and First Sergeant Gerald Aubin [Company C, 4th Battalion, 10th Infantry] who were all killed by sniper fire on the 9th and 10th in Colon and Specialist Michael W. Rowland (3rd Battalion, 508th Airborne Infantry), whose death was caused by an accidental fall into a ravine on the evening of the 10th.

Some of the more seriously injured were left with severe permanent brain damage or paralyzing spinal injuries from their bullet wounds.

Years after the events of January 1964, a number of U.S. Army historical documents were declassified, including Southcom's figures for ammunition expended.

The same account said that the Canal Zone police fired 1,850 .38 caliber pistol bullets and 600 shotgun shells in the fighting, while using only 132 tear gas grenades.

No action was taken on Panama's motion to brand the United States guilty of aggression, but the committee did accuse the Americans of using unnecessary force.

On January 15, President Chiari declared that Panama would not re-establish diplomatic ties with the U.S. until it agreed to open negotiations on a new treaty.

A few weeks later, Robert B. Anderson, President Johnson's special representative, flew to Panama to pave the way for future talks.

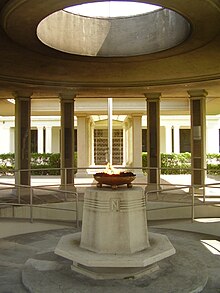

One was built where the flagpole incident happened, the former Balboa High School, today a Panama Canal Authority building that bears the name of Ascanio Arosemena, known as the first "martyr" and maybe the most famous one.

It was built by the Panama Canal Authority and consists on a covered entryway containing the memorial, which has a name of a "martyr" on each column, and an eternal fire (not unlike the eternal fire for U.S. President John F. Kennedy) in the middle, and the Panamanian flag afterwards, in a sort of open-to-the-sky (i.e. no roof) "square", on a flagpole.

The monument reflects the photograph that was on the cover of Life, in which three students scaled the 3.7-metre (12 ft) high safety fence and climbed a lamppost and the one in the top had a Panamanian flag.