Mary Kingsley

Mary Henrietta Kingsley (13 October 1862 – 3 June 1900) was an English ethnographer, writer and explorer who made numerous travels through West Africa and wrote several books on her experiences there.

The family moved to Highgate less than a year after her birth, the same home where her brother Charles George R. ("Charley") Kingsley was born in 1866, and by 1881 were living in Southwood House, Bexley in Kent.

It is possible that her father's views on the brutal treatment of Native Americans in the United States helped shape Mary's later opinions on European colonialism in West Africa.

[5] Mary Kingsley had little formal schooling compared to her brother, other than German lessons at a young age;[6] because, at that time and at her level of society, education was not thought to be necessary for a girl.

[8] She did not enjoy novels that were deemed more appropriate for young ladies of the time, such as those by Jane Austen or Charlotte Brontë, but preferred books on the sciences and memoirs of explorers.

In 1886, her brother Charley entered Christ's College, Cambridge, to read law; this allowed Mary to make several academic connections and a few friends.

There is little indication that Kingsley was raised Christian; instead, she was a self-proclaimed believer with, "summed up in her own words [...] 'an utter faith in God'" and even identified strongly with what was described as 'the African religion'.

In April, she became acquainted with Scottish missionary Mary Slessor, another European woman living among native African populations with little company and no husband.

Missionaries in Africa often required converted men to abandon all but one of their wives, leaving the other women and children without the support of a husband – thus creating immense social and economic problems.

[20] Yet in Studies in West Africa she writes: "Although a Darwinian to the core, I doubt if evolution in a neat and tidy perpendicular line, with Fetish at the bottom and Christianity at the top, represents the true state of affairs.

"[21] Other, more acceptable, beliefs were variously perceived and used in Western European society – by traders, colonists, women's rights activists and others – and, articulated as they were in great style, helped shape popular perception of "the African" and "his" land.

Though some have argued that such refusals were grounded in the anti-imperialist arguments presented in Kingsley's works, this unlikely explains her frequently unfavourable reception in Europe, because she was both a supporter of the activities of European traders in West Africa and of indirect rule.

[14][6] The notable success of Travels in West Africa was due in no small part to the vigour and droll humour of her writing, that, in the guise of a ripping yarn, never wavers from its true purpose—to complete the work her father had left undone.

Between poles of manifest wit and latent analysis Kingsley constructs in images – "… not an artist's picture, but a photograph, an overladen with detail, colourless version"[23] – a discourse of poetic thought; a phenomenon oft-noted in the texts of Walter Benjamin.

It is, rather, in the text of his daughter – a forerunner of Lévi-Strauss and his Tristes Tropiques[26] – that the dream wish of the father is finally accomplished; and family honour sustained.

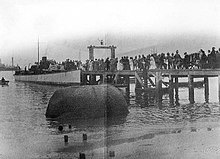

[29] "This was, I believe, the only favour and distinction that she ever asked for herself; and it was accorded with every circumstance and honour ... A party of West Yorkshires, with band before them, drew the coffin from the hospital on a gun carriage to the pier … Torpedo Boat No.

"[28] "A touch of comedy, which would 'have amused' Kingsley herself, was added when the coffin refused to sink and had to be hauled back on board then thrown over again weighed down this time with an anchor.