Mary van Kleeck

Retiring from the Sage Foundation in 1948, van Kleeck ran for New York State Senate as a member of the American Labor Party, but lost the election and turned her focus to peace activism and nuclear disarmament.

[5] The youngest of five siblings, including a brother who died in infancy, Van Kleeck was close to her mother, but had a distant relationship with her father, who was often sick when she was young.

[9][10] As part of this work, van Kleeck carried out investigations of the enforcement of the labor law governing the workweek (limited to 60 hours at the time, though this provision was frequently ignored by employers).

She studied under the experienced labor economist Henry Rogers Seager[1][9] and sociologists Franklin Giddings and Samuel McCune Lindsay, but never completed a doctoral degree.

[15] Mentored and trained by Florence Kelley and Lilian Brandt,[16] prominent older labor activists and social reformers, van Kleeck was hired directly by the Foundation in 1910 to lead its Committee on Women's Work.

[20] The Remington Arms manufacturing company, criticized by van Kleeck's department in 1916 for providing substandard conditions for its workers, attempted to suppress the resulting report, but was rebuffed by Robert DeForest, the foundation's vice president.

[8][22] For instance, she authored an article in the Journal of Political Economy arguing that working girls should be able to access evening school courses without financial barriers, published in May 1915.

[24] At Columbia, Van Kleeck encountered the ideas of Taylorism (also known as scientific management) and rapidly became a proponent,[24] viewing it as a "social science of utopian potential."

[26] The Women in Industry Service group produced a series of reports documenting wage disparities, unsafe working conditions, and discrimination against female workers, conducting investigations in 31 states.

[28] Van Kleeck made it a priority to appoint a black woman to the staff of the Women in Industry Service group, working with George Haynes to find a suitable candidate.

[12] The foundation continued to perform in-depth studies of conditions for workers at workplaces such as the Rockefeller coal and steel works (in cooperation with Ben Selekman),[24] the Dutchess Bleachery, and Filene's Department Store.

These studies collectively represented "one of the decade's most searching examinations of the dramatic changes underway in the relationship between capital, labor, stockholders, and management," according to the economic historian Mark Hendrickson.

Chaired by Hoover, who was then Secretary of Commerce, the unemployment committee developed a plan for the uniform calculation of employment statistics across the United States, work in which van Kleeck played a key role.

[24] In 1924, Will H. Hays, the powerful head of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, asked van Kleeck to undertake a study of the casting industry in Hollywood, which he believed was rife with exploitation.

A 1926 profile of van Kleeck in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, focusing on her prodigy with mathematics and statistics, described her as "an unassuming woman who goes about her work in a quiet manner, who does it primarily because she loves it, and who thoroughly enjoys every minute of her existence."

In response to the interviewer's description of her statistical reports as "endless labor", van Kleeck replied "Really, I don't feel I've worked an hour in my whole life ...

"[36] Some years later, a young contemporary of van Kleeck's, Jacob Fisher, would describe her as having "the patrician carriage and speech, the imperious presence and the grande dame manner of the mistress of a nineteenth-century salon.

"[10] Fleddérus, a Dutch social reformer, became van Kleeck's lifelong partner and the two women lived together for most of their later life, splitting their time evenly between the Netherlands and New York City each year and exchanging daily letters when apart.

[38] The historian Jacqueline Castledine characterizes their relationship as romantic, describing van Kleeck and Fleddérus as "women-committed women" in a time before lesbianism was acceptable in mainstream society.

[39] In 1932, as a longtime advocate of social-economic planning, van Kleeck visited the Soviet Union, which she viewed as being at the forefront of scientific management and labor rights.

[39] Although several fellow social scientists and activists advocated for van Kleeck to receive a cabinet position in the new Roosevelt administration in 1933, her increasingly radical views made this unlikely.

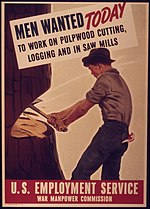

Although appointed to the Federal Advisory Council of the New Deal U.S. Employment Service, she resigned in protest after one day due to her belief that the National Recovery Administration was not sufficiently supportive of unions.

"[10]During the early years of the New Deal, van Kleeck was considered a leading figure of the American left, with considerable influence over the national social work movement, which advocated for progressive improvements in society.

This reaction alarmed more conservative members of the NCSW and led its president, William Hodson, to criticize van Kleeck's radicalism and opposition to the New Deal at the organization's annual banquet.

[17] She ran for New York State Senate the same year as a member of the far-left American Labor Party in Manhattan's 20th District, against incumbent Republican MacNeil Mitchell and Democrat Evelyn B.

[14][38] As an openly dedicated socialist, van Kleeck was called before Joseph McCarthy's Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in 1953, where she was represented by civil rights lawyer Leonard Boudin and questioned by Roy Cohn.

I am a believer in political democracy, which is the essence of the United States of America.What interests me in my life is my work, for it was my unusual and blessed destiny to be involved with subjects of immense importance.

In 1956, on the recommendation of Eleanor Flexner, van Kleeck began organizing her papers and turning them over to the Sophia Smith Collection at her alma mater, with the assistance of Margaret Storrs Grierson.

Van Kleeck had been uncertain whether her documents were of value, saying that "to write about [national issues] with merely me as the unifying element would belittle them to the vanishing point," but came around to believe that "the collection, if properly arranged, would be the most useful biography.