Battle of Fredericksburg

Burnside ordered the Right and Center Grand Divisions of major generals Edwin V. Sumner and Joseph Hooker to launch multiple frontal assaults against Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's position on Marye's Heights – all were repulsed with heavy losses.

In November 1862, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln needed to demonstrate the success of the Union war effort before the Northern public lost confidence in his administration.

Burnside had established a reputation as an independent commander, with successful operations earlier that year in coastal North Carolina and, unlike McClellan, had no apparent political ambitions.

Aware that Lee had blocked the O&A, McClellan considered a route through Fredericksburg and ordered a small group of cavalrymen commanded by Captain Ulric Dahlgren to investigate the condition of the RF&P.)

Lincoln reluctantly approved the plan on November 14 but cautioned his general to move with great speed, certainly doubting that Lee would react as Burnside anticipated.

[16] As Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner arrived, he strongly urged an immediate crossing of the river to scatter the token Confederate force of 500 men in the town and occupying the commanding heights to the west.

But when he saw how slowly Burnside was moving (and Confederate President Jefferson Davis expressed reservations about planning for a battle so close to Richmond), he directed all of his army toward Fredericksburg.

[18] The boats and equipment for a single pontoon bridge arrived at Falmouth on November 25, much too late to enable the Army of the Potomac to cross the river without opposition.

[23] The clearing of the city buildings by Sumner's infantry and by artillery fire from across the river began the first major urban combat of both the war and American history.

At 5:00 p.m. on December 12, he made a cursory inspection of the southern flank, where Franklin and his subordinates pressed him to give definite orders for a morning attack by the grand division, so they would have adequate time to position their forces overnight.

They moved parallel to the river initially, turning right to face the Richmond Road, where they began to be struck by enfilading fire from the Virginia Horse Artillery under Major John Pelham.

Hill's division's line, a triangular patch of the woods that extended beyond the railroad was swampy and covered with thick underbrush and the Confederates had left a 600-yard gap there between the brigades of Brig.

The attack did not have the benefit of a gap to exploit, nor did the Union soldiers have any wooded cover for their advance, so progress was slow under heavy fire from Lane's brigade and Confederate artillery.

Birney claimed that his men had been subjected to damaging artillery fire as they formed up, that he had not understood the importance of Meade's attack, and that Reynolds had not ordered his division forward.

When Meade galloped to the rear to confront Birney with a string of fierce profanities that, in the words of one staff lieutenant, "almost makes the stones creep," he was finally able to order the brigadier forward under his own responsibility, but harbored resentment for weeks.

Gen. Archer, and Col. John M. Brockenbrough to charge forward out of the railroad ditches, driving Meade's men from the woods in a disorderly retreat, followed closely by Gibbon's.

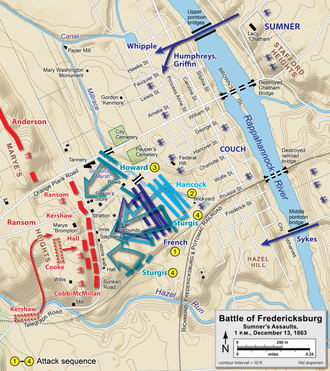

Gen. William H. French's division of the II Corps prepared to move forward, subjected to Confederate artillery fire that was descending on the fog-covered city of Fredericksburg.

They advanced slowly through heavy artillery fire, crossed the canal in columns over the narrow bridges, and formed in line, with fixed bayonets, behind the protection of a shallow bluff.

Miles suggested to Caldwell that the practice of marching in formation, firing, and stopping to reload, made the Union soldiers easy targets, and that a concerted bayonet charge might be effective in carrying the works.

He first considered a massive bayonet charge to overwhelm the defenders, but as he surveyed the front, he quickly realized that French's and Hancock's divisions were in no shape to move forward again.

Gen. George Sykes was ordered to move forward with his V Corps regular army division to support Humphreys's retreat, but his men were caught in a crossfire and pinned down.

[53] Thousands of Union soldiers spent the cold December night on the fields leading to the heights, unable to move or assist the wounded because of Confederate fire.

[54] During a dinner meeting the evening of December 13, Burnside dramatically announced that he would personally lead his old IX Corps in one final attack on Marye's Heights, but his generals talked him out of it the following morning.

[56] Testament to the extent of the carnage and suffering during the battle was the story of Richard Rowland Kirkland, a Confederate Army sergeant with Company G, 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry.

Stationed at the stone wall by the sunken road below Marye's Heights, Kirkland had a close up view to the suffering and like so many others was appalled at the cries for help of the Union wounded throughout the cold winter night of December 13, 1862.

The event was noted in the diaries and letters of many soldiers at Fredericksburg, such as John W. Thompson, Jr., who wrote "Louisiana sent those famous cosmopolitan Zouaves called the Louisiana Tigers, and there were Florida troops who, undismayed in fire, stampeded the night after Fredericksburg, when the Aurora Borealis snapped and crackled over that field of the frozen dead hard by the Rappahannock ..."[59] The Union army suffered 12,653 casualties (1,284 killed, 9,600 wounded, 1,769 captured/missing).

We had really accomplished nothing; we had not gained a foot of ground, and I knew the enemy could easily replace the men he had lost, and the loss of material was, if anything, rather beneficial to him, as it gave an opportunity to contractors to make money.

The Cincinnati Commercial noted, "It can hardly be in human nature for men to show more valor or generals to manifest less judgment, than were perceptible on our side that day."

Gen. John Gibbon launched their assault against Lt. Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's Confederates holding the southern portion of the Army of Northern Virginia's line at Fredericksburg.

Despite suffering enormous casualties the Federal troops under Meade were able to temporarily penetrate the Confederate line and for a time represented the North's best chance of winning the Battle of Fredericksburg.