Mass in B minor structure

Joshua Rifkin notes: ... likely, Bach sought to create a paradigmatic example of vocal composition while at the same time contributing to the venerable musical genre of the Mass, still the most demanding and prestigious apart from opera.

He presented that composition to Frederick Augustus II, Elector of Saxony (later, as Augustus III, also king of Poland),[1] accompanied by a letter:In deepest Devotion I present to your Royal Highness this small product of that science which I have attained in Musique, with the most humble request that you will deign to regard it not according to the imperfection of its Composition, but with a most gracious eye ... and thus take me into your most mighty Protection.

For example, Gratias agimus tibi (We give you thanks) is based on Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir[9] (We thank you, God, we thank you) and the Crucifixus (Crucified) is based on the general lamenting about the situation of the faithful Christian, Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen[9] (Weeping, lamenting, worrying, fearing) which Bach had composed already in 1714 as one of his first cantatas for the court of Weimar.

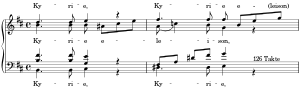

[11] The parts Kyrie, Gloria and Credo are all designed with choral sections as the outer movements, framing an intimate center of theological significance.

[20] Christoph Wolff notes a similarity between the fugue theme and one by Johann Hugo von Wilderer, whose mass Bach had probably copied and performed in Leipzig before 1731.

[19] The second acclamation of God is a four-part choral fugue, set in stile antico, with the instruments playing colla parte.

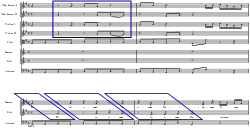

[28] In further symmetry, the opening in two different tempos corresponds to the final sequence of an aria leading to "Cum sancto spiritu", the soprano II solo with obbligato violin "Laudamus te" to the alto solo with obbligato oboe "Qui sedes", and the choral movements "Gratias" and "Qui tollis" frame the central duet of soprano I and tenor "Domine Deus".

Bach used this section, the central duet and the concluding doxology as a Christmas cantata, Gloria in excelsis Deo, BWV 191 (Glory to God in the Highest), probably in 1745, a few years before the compilation of the Mass.

[29] The first thought, "Gloria in excelsis Deo" (Glory to God in the Highest), is set in 3/8 time, compared by Wenk to the Giga, a dance form.

The duration of an eighth note stays the same, Bach thus achieves a contrast of "heavenly" three eights, a symbol of the Trinity, and "earthly" four quarters.

[39] When the text reaches the phase "Qui tollis peccata mundi" (who takest away the sins of the world), the music is given attacca to a four-part choir with two obbligato flutes.

[41] The continuation of the thought, "Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris" (who sits at the right [hand] of the Father), is expressed by an aria for alto and obbligato oboe d'amore.

[30] The last section begins with an aria for bass, showing "Quoniam tu solus sanctus" (For you alone are holy) in an unusual scoring of only corno da caccia and two bassoons.

[43] By using the polonaise, Bach not only expressed the text by musical means, but also paid respect to the King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, August III, to whom the Mass is dedicated.

[18] The part begins and ends with a sequence of two connected choral movements in contrasting style, a motet in stile antico, containing a chant melody, and a concerto.

Musicologist John Butt summarizes: "By using numerous stile antico devices in a particular order and combination, Bach has created a movement in which a standardised structure breeds a new momentum of its own".

The bass introduces the theme, without an instrumental opening, while the other voices repeat simultaneously in homophony "Credo in unum Deum" as a firm statement.

When Bach treated "Et incarnatus est" as a separate choral movement, he rearranged the text, and the figure lost its "pictorial association".

The humiliation of God, born as man, is illustrated by the violins in a pattern of one measure that descends and then combines the symbol of the cross and sighing motifs, alluding to the crucifixion.

[61] The concerto on ascending motifs[49] renders the resurrection, the ascension and the second coming, all separated by long instrumental interludes and followed by a postlude.

Speaking about the third person of the Trinity, the number three appears in many aspects: the aria is in three sections, in a triple 6/8-time, in A major, a key with three sharps, in German "Kreuz" (cross).

[29] Then the movement slows down to Adagio (a written tempo change, rare in Bach), as the altos sing the word "peccatorum" (sinners) one last time in an extremely low range.

Whenever the word "mortuorum" appears, the voices sing long low notes, whereas "resurrectionem" is illustrated in triad motifs leading upwards.

[9] After this statement, which ends in homophony, the instruments begin a short section in which runs in rising sequences alternate with the fanfare, in which the voices are later embedded.

A second repetition of instruments, embedded voices and upward runs brings the whole section to a jubilant close on the words "et vitam venturi saeculi.

[30] Sanctus (Holy) is an independent movement written for Christmas 1724, scored for six voices SSAATB and a festive orchestra with trumpets and three oboes.

[69] The continuation, "Pleni sunt coeli" (Full are the heavens), follows immediately, written for the same scoring, as a fugue in dancing 3/8 time with "quick runs".

[30] The following thought, Benedictus, "blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord", is sung by the tenor in an aria with an obbligato instrument, probably a flauto traverso,[29] leading to a repeat of the Osanna.

[76] It was the basis also for the fourth movement of the Ascension Oratorio, Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen, BWV 11, the aria Ach, bleibe doch, mein liebstes Leben.

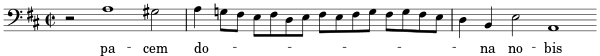

[69] The final movement, Dona nobis pacem (Give us peace), recalls the music of thanks expressed in Gratias agimus tibi.