Mass in the Catholic Church

The Mass is the central liturgical service of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, in which bread and wine are consecrated and become the body and blood of Christ.

[7][8] On 16 July 2021 Pope Francis in his apostolic letter Traditionis custodes restricted the celebration of the Tridentine Mass of the Roman Rite and declared that "the liturgical books promulgated by Saint Paul VI and Saint John Paul II, in conformity with the decrees of Vatican Council II, are the unique expression of the lex orandi of the Roman Rite.

[13] Paul F. Bradshaw and Maxwell E. Johnson trace the history of eucharistic liturgies from first-century shared meals of Christian communities, which became associated with the Last Supper, to second and third-century rites mentioned by Pliny the Younger and Ignatius of Antioch and described by Justin Martyr and others, in which passages from Scripture were read and the use of bread and wine was no longer associated with a full meal.

Ex tempore prayers by the presider gave way to texts previously approved by synods of bishops as a guarantee of the orthodoxy of the content, leading to the formation of liturgical forms or "rites" generally associated with influential episcopal sees.

The following description of the celebration of Mass, usually in the local vernacular language, is limited to the form of the Roman Rite promulgated after the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) by Pope Paul VI in 1969 and revised by Pope John Paul II in 2002, largely replacing the usage of the Tridentine Mass form originally promulgated in 1570 in accordance with decrees of the Council of Trent in its closing session (1545–46).

The 1962 form of the Tridentine Mass, in the Latin language alone, may be employed where authorized by the Holy See or, in the circumstances indicated in the 2021 document Traditionis custodes,[17] by the diocesan bishop.

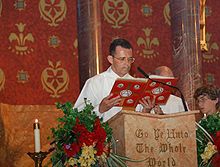

The Eucharistic celebration is "one single act of worship" but consists of different elements, which always include "the proclamation of the Word of God; thanksgiving to God the Father for all his benefits, above all the gift of his Son; the consecration of bread and wine, which signifies also our own transformation into the body of Christ;[24] and participation in the liturgical banquet by receiving the Lord's body and blood".

Then, when the priest arrives at his chair, he leads the assembly in making the Sign of the Cross, saying: "In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit",[28][29] to which the faithful answer: "Amen."

If there are three readings, the first is from the Old Testament (a term wider than Hebrew Scriptures, since it includes the Deuterocanonical Books), or the Acts of the Apostles during Eastertide.

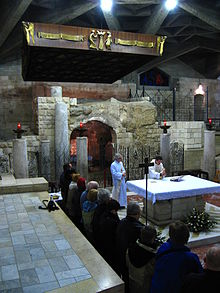

The linen corporal is spread over the center of the altar, and the Liturgy of the Eucharist begins with the ceremonial placing on it of bread and wine.

[40] The unleavened, wheat bread (in the tradition of the Latin Church)[41] is placed on a paten, and the wine (from grapes) is put in a chalice and mixed with a little water, As the priest places each on the corporal, he says a silent prayer over each individually, which, if this rite is unaccompanied by singing, he is permitted to say aloud, in which case the congregation responds to each prayer with: "Blessed be God forever."

This dialogue opens with the normal liturgical greeting, "The Lord be with you", but in view of the special solemnity of the rite now beginning, the priest then exhorts the faithful: "Lift up your hearts."

If a person is unable to kneel, he makes a profound bow after the Consecration[45] – the Institution Narrative that recalls Jesus' words and actions at his Last Supper: "Take this, all of you, and eat of it: for this is my body which will be given up for you.

[47] The Eucharistic Prayer includes the Epiclesis (which since early Christian times the Eastern churches have seen as the climax of the Consecration), praying that the Holy Spirit might transform the elements of bread and wine and thereby the people into one body in Christ.

This is in line with the Instruction on Music in the Liturgy which says: "One cannot find anything more religious and more joyful in sacred celebrations than a whole congregation expressing its faith and devotion in song.

The priest adds to it a development of the final petition, known as the embolism: "Deliver us, Lord, we pray, from every evil, graciously grant peace in our days, that, by the help of your mercy, we may be always free from sin and safe from all distress, as we await the blessed hope and the coming of our Savior, Jesus Christ."

Some recognized experts on the rubrics of the Roman Rite, the liturgists Edward McNamara and Peter Elliott, deplore the adoption of either of these postures by the congregation as a body,[55][56] and both are subject to controversy.

The form of the sign of peace varies according to local custom for a respectful greeting (for instance, a handshake or a bow between strangers, or a kiss/hug between family members).

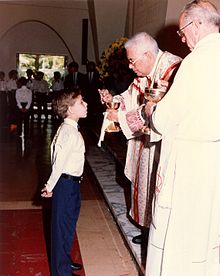

The priest breaks the host and places a piece in the main chalice; this is important as it symbolizes that the Body and Blood of Christ are both present within one another.

[78] While Communion is distributed, singing of an appropriate approved chant or hymn is recommended, to emphasize the essentially "communitarian" nature of the body of Christ.

[80] "The sacred vessels are purified by the priest, the deacon, or an instituted acolyte after Communion or after Mass, insofar as possible at the credence table.

The priest and other ministers then venerate the altar with a kiss, form a procession, and exit the sanctuary, preferably to a recessional hymn or chant from the Graduale, sung by all.

[citation needed] The Mass being over, the faithful may depart or stay a while, pray, light votive candles at shrines in the church, converse with one another, etc.

In some countries, including the United States, the priest customarily stands outside the church door to greet the faithful individually as they exit.

In particularly difficult circumstances, the Pope can grant the diocesan bishop permission to give his priests faculties to trinate on weekdays and quadrinate on Sundays.

Permission for four Masses on one day has been obtained in order to cope with large numbers of Catholics either in mission lands or where the ranks of priests are diminishing.

For most of the second millennium, before the twentieth century brought changes beginning with Pope Pius X's encouragement of frequent Communion, the usual Mass was said exactly the same way whether people other than a server were present or not.

[92] Moral theologians gave their opinions on how much time the priest should dedicate to celebrating a Mass, a matter on which canon law and the Roman Missal were silent.

[citation needed] The Ritual Mass texts may not be used, except perhaps partially, when the rite is celebrated during especially important liturgical seasons or on high ranking feasts.

The Nuptial Mass contains special prayers for the couple and, in the ordinary form of the Roman Rite, may be offered at any time of the liturgical year, except during the Paschal Triduum.