Magister militum

These offices had precedents in the immediate imperial past, both in function and idea;[1] the latter title had existed since republican times, as the second-in-command to a Roman dictator.

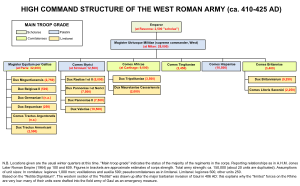

Over the course of the fourth century in the Western Roman Empire, the system of two imperial magistri remained largely intact, with usually one magister having paramount authority (such as Bauto or Merobaudes, the main power behind the appointment of emperor Valentinian II.)

In the west, the position (often under the title of magister utriusque militiae or MVM) remained very powerful until the formal end of the empire, and was held by Stilicho, Aetius, Ricimer, and others.

In the course of the 6th century, internal and external crises in the provinces often necessitated the temporary union of the supreme regional civil authority with the office of the magister militum.

Supreme military commanders sometimes also took this title in early medieval Italy, for example in the Papal States and in Venice, whose Doge claimed to be the successor to the Exarch of Ravenna.

In the Gesta Herwardi, the hero is several times described as magister militum by the man who translated the original Old English account into Medieval Latin.