Matchlock

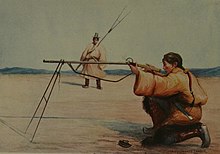

The classic matchlock gun held a burning slow match in a clamp at the end of a small curved lever known as the serpentine.

Upon the pull of a lever (or in later models a trigger) protruding from the bottom of the gun and connected to the serpentine, the clamp dropped down, lowering the smoldering match into the flash pan and igniting the priming powder.

The flash from the primer traveled through the touch hole, igniting the main charge of propellant in the gun barrel.

As the match was often extinguished after its collision with the flash pan, this type was not used by soldiers but was often used in fine target weapons where the precision of the shot was more important than the repetition.

This was chiefly a problem in wet weather, when damp match cord was difficult to light and to keep burning.

It was also quite dangerous when soldiers were carelessly handling large quantities of gunpowder (for example, while refilling their powder horns) with lit matches present.

This was one reason why soldiers in charge of transporting and guarding ammunition were amongst the first to be issued self-igniting guns like the wheellock and snaphance.

[5] Robert Elgood theorizes the armies of the Italian states used the arquebus in the 15th century, but this may be a type of hand cannon, not matchlocks with trigger mechanism.

[18] While the Japanese were technically able to produce tempered steel (e.g. sword blades), they preferred to use work-hardened brass springs in their matchlocks.

The name tanegashima came from the island where a Chinese junk (a type of ship) with Portuguese adventurers on board was driven to anchor by a storm.

[19] Despite the appearance of more advanced ignition systems, such as that of the wheellock and the snaphance, the low cost of production, simplicity, and high availability of the matchlock kept it in use in European armies.

During the Sino-French War, the Hakka and Aboriginals used their matchlock muskets against the French in the Keelung Campaign and Battle of Tamsui.