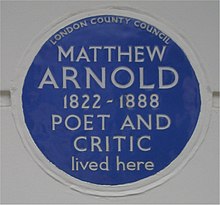

Matthew Arnold

He attended John Henry Newman's sermons at the University Church of St Mary the Virgin but did not join the Oxford Movement.

Wishing to marry but unable to support a family on the wages of a private secretary, Arnold sought the position of and was appointed in April 1851 one of Her Majesty's Inspectors of Schools.

Although his duties were later confined to a smaller area, Arnold knew the society of provincial England better than most of the metropolitan authors and politicians of the day.

[12] Arnold died suddenly in 1888 of heart failure whilst running to meet a tram that would have taken him to the Liverpool Landing Stage to see his daughter, who was visiting from the United States where she had moved after marrying an American.

[14] Arnold was a familiar figure at the Athenaeum Club, a frequent diner-out and guest at great country houses, charming, fond of fishing (but not of shooting),[15] and a lively conversationalist, with a self-consciously cultivated air combining foppishness and Olympian grandeur.

In his writings, he often baffled and sometimes annoyed his contemporaries by the apparent contradiction between his urbane, even frivolous manner in controversy, and the "high seriousness" of his critical views and the melancholy, almost plaintive note of much of his poetry.

[citation needed] Arnold's literary career—aside from two youthful prize poems—had begun in 1849 with the publication of The Strayed Reveller and Other Poems by A., which attracted little notice and was soon withdrawn.

In 1858 he published his tragedy of Merope, calculated, he wrote to a friend, "rather to inaugurate my Professorship with dignity than to move deeply the present race of humans," and chiefly remarkable for some experiments in unusual—and unsuccessful—metres.

Of his poetry, Bloom says, Whatever his achievement as a critic of literature, society, or religion, his work as a poet may not merit the reputation it has continued to hold in the twentieth century.

... Arnold's poetry continues to have scholarly attention lavished upon it, in part because it seems to furnish such striking evidence for several central aspects of the intellectual history of the nineteenth century, especially the corrosion of 'Faith' by 'Doubt'.

No poet, presumably, would wish to be summoned by later ages merely as an historical witness, but the sheer intellectual grasp of Arnold's verse renders it peculiarly liable to this treatment.

With its emphasis on the importance of subject in poetry, on "clearness of arrangement, rigor of development, simplicity of style" learned from the Greeks, and in the strong imprint of Goethe and Wordsworth, may be observed nearly all the essential elements in his critical theory.

"[28] Criticism began to take first place in Arnold's writing with his appointment in 1857 to the professorship of poetry at Oxford, which he held for two successive terms of five years.

Especially characteristic, both of his defects and his qualities, are on the one hand, Arnold's unconvincing advocacy of English hexameters and his creation of a kind of literary absolute in the "grand style," and, on the other, his keen feeling of the need for a disinterested and intelligent criticism in England.

[citation needed] Although Arnold's poetry received only mixed reviews and attention during his lifetime, his forays into literary criticism were more successful.

"[32][33] Arnold viewed with scepticism the plutocratic grasping in socioeconomic affairs, and engaged the questions which vexed many Victorian liberals on the nature of power and the state's role in moral guidance.

"[35] The Philistines were "humdrum people, slaves to routine, enemies to light" who believed that England's greatness was due to her material wealth alone and took little interest in culture.

[35] Liberal education was essential, and by that Arnold meant a close reading and attachment to the cultural classics, coupled with critical reflection.

[36] Arnold saw the "experience" and "reflection" of Liberalism as naturally leading to the ethical end of "renouncement," as evoking the "best self" to suppress one's "ordinary self.

"[33] Despite his quarrels with the Nonconformists, Arnold remained a loyal Liberal throughout his life, and in 1883, William Gladstone awarded him an annual pension of 250 pounds "as a public recognition of service to the poetry and literature of England.

"[37][38][39] Many subsequent critics such as Edward Alexander, Lionel Trilling, George Scialabba and Russell Jacoby have emphasised the liberal character of Arnold's thought.

"There are four people, in especial," he once wrote to Cardinal Newman, "from whom I am conscious of having learnt—a very different thing from merely receiving a strong impression—learnt habits, methods, ruling ideas, which are constantly with me; and the four are—Goethe, Wordsworth, Sainte-Beuve, and yourself."

Others such as Stefan Collini suggest that much of the criticism aimed at Arnold is based on "a convenient parody of what he is supposed to have stood for" rather than the genuine article.

[33] In 1887, Arnold was credited with coining the phrase "New Journalism", a term that went on to define an entire genre of newspaper history, particularly Lord Northcliffe's turn-of-the-century press empire.

In his account of that tour, "Civilization in the United States", he observed, "if one were searching for the best means to efface and kill in a whole nation the discipline of self-respect, the feeling for what is elevated, he could do no better than take the American newspapers.

Under the influence of Baruch Spinoza and his father, Dr. Thomas Arnold, he rejected the supernatural elements in religion,[50] even while retaining a fascination for church rituals.

"[54] Harold Bloom writes that "Whatever his achievement as a critic of literature, society or religion, his work as a poet may not merit the reputation it has continued to hold in the twentieth century.

Arnold is, at his best, a very good, but highly derivative poet, unlike Tennyson, Browning, Hopkins, Swinburne and Rossetti, all of whom individualized their voices.