Matthew Boulton

In the final quarter of the 18th century, the partnership installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engines, which were a great advance on the state of the art, making possible the mechanisation of factories and mills.

Members of the Society have been given credit for developing concepts and techniques in science, agriculture, manufacturing, mining, and transport that laid the groundwork for the Industrial Revolution.

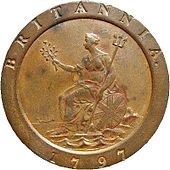

His "cartwheel" pieces were well designed and difficult to counterfeit, and included the first striking of the large copper British penny, which continued to be coined until decimalisation in 1971.

[1] With the town far from the sea and great rivers, and with canals not yet built, metalworkers concentrated on producing small, relatively valuable pieces, especially buttons and buckles.

[1] Frenchman Alexander Missen wrote that while he had seen excellent cane heads, snuff boxes and other metal objects in Milan, "the same can be had cheaper and better in Birmingham".

[6] The elder Boulton's business prospered after young Matthew's birth, and the family moved to the Snow Hill area of Birmingham, then a well-to-do neighbourhood of new houses.

They lived briefly with the bride's mother in Lichfield, and then moved to Birmingham, where the elder Matthew Boulton made his son a partner at the age of 21.

His eldest son Matthew Piers Watt Boulton, broadly educated and also a man of science,[16] gained some fame posthumously for his invention of the important aeronautical flight control, the aileron.

[27] Towards the end of the 18th century, Boulton and his followers expanded production at the Soho Manufactory to include shoe buckles and seals, marking Birmingham's rise as a centre for both silver plate and mass-produced metal goods.

[29] Boulton wrote in 1771, "I am very desirous of becoming a great silversmith, yet I am determined not to take up that branch in the large way I intended, unless powers can be obtained to have a marking hall [assay office] at Birmingham.

Though the petition was bitterly opposed by London goldsmiths, he was successful in getting Parliament to pass an act establishing assay offices in Birmingham and Sheffield, whose silversmiths had faced similar difficulties in transporting their wares.

The Christie's exhibition succeeded in publicising Boulton and his products, which were highly praised, but the sales were not financially successful with many works left unsold or sold below cost.

With the assistance of iron master John Wilkinson (brother-in-law of Lunar Society member Joseph Priestley), they succeeded in making the engine commercially viable.

The company made its profit by comparing the amount of coal used by the machine with that used by an earlier, less efficient Newcomen engine, and required payments of one-third of the savings annually for the next 25 years.

[57] Mine owners were also reluctant to make the annual payments, viewing the engines as theirs once erected, and threatened to petition Parliament to repeal Watt's patent.

On a 1781 visit to Wales Boulton had seen a powerful copper-rolling mill driven by water, and when told it was often inoperable in the summer due to drought suggested that a steam engine would remedy that defect.

[64] Before its 1791 destruction by fire, the mill's fame, according to early historian Samuel Smiles, "spread far and wide", and orders for rotative engines poured in not only from Britain but from the United States and the West Indies.

In a letter to the Master of the Mint, Lord Hawkesbury (whose son would become Prime Minister as Earl of Liverpool) on 14 April 1789, Boulton wrote: In the course of my journeys, I observe that I receive upon an average two-thirds counterfeit halfpence for change at toll-gates, etc.

and I believe the evil is daily increasing, as the spurious money is carried into circulation by the lowest class of manufacturers, who pay with it the principal part of the wages of the poor people they employ.

[78] Boulton spent much time in London lobbying for a contract to strike British coins, but in June 1790 the Pitt Government postponed a decision on recoinage indefinitely.

[72] The firm sent over 20 million blanks to Philadelphia, to be struck into cents and half-cents by the United States Mint[80]—Mint Director Elias Boudinot found them to be "perfect and beautifully polished".

His associate and fellow Lunar Society member James Keir eulogised him after his death: Mr. [Boulton] is proof of how much scientific knowledge may be acquired without much regular study, by means of a quick & just apprehension, much practical application, and nice mechanical feelings.

[92] In 1758 the Pennsylvania printer Benjamin Franklin, the leading experimenter in electricity, journeyed to Birmingham during one of his lengthy stays in Britain; Boulton met him, and introduced him to his friends.

[93] He wrote in his notebooks observations on the freezing and boiling point of mercury, on people's pulse rates at different ages, on the movements of the planets, and on how to make sealing wax and disappearing ink.

[95] However, Erasmus Darwin, another fellow enthusiast who became a member of the Lunar Society, wrote to him in 1763, "As you are now become a sober plodding Man of Business, I scarcely dare trouble you to do me a favour in the ... philosophical way.

Its members were brilliant representatives of the informal scientific web which cut across class, blending the inherited skills of craftsmen with the theoretical advances of scholars, a key factor in Britain's leap ahead of the rest of Europe.

[103] He also supported Birmingham's Oratorio Choral Society, and collaborated with button maker and amateur musical promoter Joseph Moore to put on a series of private concerts in 1799.

[112] His continued activity distressed Watt, who had entirely retired from Soho, and who wrote to Boulton in 1804, "[Y]our friends fear much that your necessary attention to the operation of the coinage may injure your health".

[113] Boulton helped deal with the shortage of silver, persuading the Government to let him overstrike the Bank of England's large stock of Spanish dollars with an English design.

The Bank had attempted to circulate the dollars by countermarking the coins on the side showing the Spanish king with a small image of George III, but the public was reluctant to accept them, in part due to counterfeiting.