Maurice Duplessis

That term saw the introduction of several key welfare policies (such as the universal minimum wage and old-age pensions), but the effort to strengthen his rule by calling a snap election in 1939 failed as his campaigning on the issue of World War II backfired and his government left the economy in a poor state.

"Le Chef"'s authoritarian inclinations, his all-powerful electoral machine, staunch conservatism and nationalism, a cozy relationship with the Catholic Church, the mistreatment of Duplessis Orphans and the apparent backwardness of his model of development were also subject of criticism.

This was also the initial general opinion of historians and intellectuals, but since the 1990s, academics have revisited Duplessism and concluded instead that this assessment required nuancing and placement in the contemporary perspective and, in some cases, advocated outright rejection of that label.

[f] The future premier was a bright student, excelling in French, history, Latin and philosophy; at the same time, he was known to be playful and sometimes mischievous (a "scamp", as Conrad Black suggests), which would often lead Duplessis into trouble.

Maurice would, as Conrad Black wrote, "enjoy, almost wallow in, extravagant but thin treatises on the founders of French Canada", where he would show his attachment to and admiration of his roots, the rural lifestyle and the Catholic faith.

Mercier benefited from a well-organized political structure in the area directed by his mentor, Jacques Bureau, who at the time served as a member of Parliament for Three Rivers and St. Maurice and the federal minister of customs and excise.

In his maiden speech on January 19, the Legislative Assembly freshman decried the overemphasis on industrial development, as opposed to rural and small-business interests and called to stop increasing taxes and to respect the religious nature of Sundays.

[11] The Conservatives increasingly grew fed up with Houde's performance, and since he was no longer an MLA, lost his Montreal mayorship election in April 1932 and had trouble maintaining his newspaper, he had little real power in the caucus.

Therefore, when in an effort to appease the Anglophone community, Houde unexpectedly designated an ageing Charles Ernest Gault, his ally and long-time MLA from Montréal–Saint-Georges, as the new leader of the parliamentary caucus, the party overrode the decision.

This choice was formally confirmed during a party congress in Sherbrooke on October 4–5, 1933, when Duplessis got 332 votes of the delegates (including from 7 out of 10 MLAs and all but one federal minister from Quebec) to 214 cast for a more moderate Onésime Gagnon, an MLA from Dorchester.

The new party, which in particular despised the big business's interests in the province, consisted of nationalist and progressive MLAs led by Paul Gouin and included some other figures, such as Philippe Hamel, Joseph-Ernest Grégoire and Oscar Drouin.

It advocated corporatism as an alternative for capitalism and communism[50] and sought to improve the position of French Canadians in the province by expanding the social welfare net, breaking (and, if needed, nationalizing) business trusts and revitalizing rural areas.

[11] It was during this term that the legislation first recognized the right to a minimum salary for everyone (the "fair wage" standard, as it was known back then, previously applied to women only), but this law saw several problems in its implementation due to lack of uniformity and reluctance of trade unions to embrace it.

Duplessis decided to seize that opportunity and announced a snap election to cement his grip on power by rallying the population around the fears of conscription (which French Canadians overwhelmingly opposed in World War I).

Joseph-Damase Bégin called to convene a caucus meeting to consider changing the leader, with Onésime Gagnon and Hormisdas Langlais as possible contenders, but Duplessis successfully quashed the effort.

[82] Duplessis had previously considered the issue several times, but, unlike some of his colleagues, largely avoided discussing it and generally either abstained on the legislation or opposed it by voting "nay" or by trying to block the bill in committee.

It was a brainchild of such figures as Lionel Groulx and Georges Pelletier [fr], the editor-in-chief of Le Devoir, and centered around André Laurendeau and Maxime Raymond,[87] who were instrumental in what was effectively the defeat of the 1942 conscription plebiscite.

[121] Even though the size of the budget increased substantially, "Le Chef" derided most attempts at welfare state in Quebec as "Anglo-Saxon and Protestant socialism";[122] instead, he called for charity to fill in the gaps.

Most of the paintings, including those by Clarence Gagnon, Cornelius Krieghoff, J. M. W. Turner, Auguste Renoir, Charles Jacque, Cornelis Springer and Johan Jongkind, are stored in the National Museum of Fine Arts of Quebec.

Shortly before the 1960 elections, Pierre Laporte published the first biography after Duplessis's death,[165] which portrayed him as an intelligent but ruthless politician who would stay in power through corruption and repression of political opponents.

Leslie Roberts' book[166] outright called Duplessis a "Latin-American dictator" who would cater to the simplistic desires of French Canadians but failed to lift them from the state of inferiority with respect to the Anglophones.

[157] Interpretations behind the label and even the dates of the beginning of this "shameful" period[158] vary, but generally revolve around the criticism of defending a regressive model of society, blocking progress and leaving patronage and corruption entrenched.

[169] Among other supporters of this interpretation were trade unionist Madeleine Parent,[170] who was imprisoned for her advocacy in 1955 and ultimately acquitted of the charge of "seditious conspiracy";[171] Gérard Pelletier, also a union organizer, who described Duplessis's views as those of a "19th-century rural notary";[172] and Jacques Hébert.

[167] Among those who changed their opinion of the regime in the course of the years was Léon Dion, who wrote in 1993 that the assessment of the period as the Grande Noirceur (as he and like-minded scholars proposed in the 1960s) was unreasonably harsh and his policies on the economy, such as the development of Northern Quebec, were reasonable or at least justifiable.

[198] Yet other historians emphasize in their opinions that the "rupture" between the Quiet Revolution and Duplessis is not present in every aspect of Quebec's life,[199] is generally exaggerated or even artificially created,[200] or else that it should be better thought of as a transitionary period.

A 1984 paper by George Steven Swan found many similarities between the policies of Duplessis and those of Huey Long, a left-populist American politician from Louisiana, and of Juan Perón of Argentina, in particular as they related to authoritarian practices.

They noted the heavy-handed approach both used for trade unions and communists, their strong anti-federalist rhetoric (even if Duplessis stopped short of advocating separatism) and extensive malapportionment that they conclude was gratuitous.

Among the suggested similarities were the party's program mirroring that of the Union Nationale,[214] ADQ's emphasis on provincial autonomy[215] and the (rather successful) usage of populist rhetoric at times when the electorate was tired of the prior state of politics.

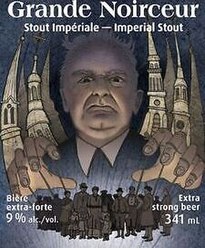

of Saint-Jérôme produces a variety of dark beer called Grande Noirceur with suggestive imagery – a caricature appearance of "Le Chef" manipulating the assembled population with strings (as if they were puppets), with church towers behind him.

In 1948, Argentine President Juan Perón gave Duplessis the highest decoration, the Grand Cross of the Order of the Liberator General San Martín, which provoked a minor diplomatic incident as the government of Canada had advised foreign emissaries not to give any such distinctions to its citizens.