Max Liebermann

In the words of arts reporter and critic, Grace Glueck, he "pushed for the right of artists to do their own thing, unconcerned with politics or ideology.

When Max was ten years old, his father Louis bought the imposing Palais Liebermann, at Pariser Platz 7, directly to the north of the Brandenburg Gate.

After an intense conflict with his father, who was not impressed by his son's path, In 1869 his parents made it possible for him to study painting and drawing at the Grand Ducal Saxon Art School in Weimar.

He volunteered for the Johannitern because a badly healed broken arm prevented him from regular military service, and served as a medic during the siege of Metz.

There he met Mihály von Munkácsy, whose realistic depiction of women plucking wool, a simple everyday scene, aroused Liebermann's interest.

When the painting was exhibited in Berlin that same year, it met with similar opinions,[7] but a buyer was found in the railway magnate Bethel Henry Strousberg.

In 1874 he submitted his goose plucking to the Salon de Paris, where the picture was accepted but received negative reviews in the press, especially from a nationalist point of view.

Ultimately, he tried to follow in Millet's footsteps and, in the opinion of contemporary critics, lagged behind him with his own achievements: The depiction of the workers in their environment seemed unnatural; it seemed as if they were added to the landscape at a later date.

[2] At the International Art Show in Munich it was denounced for its supposed blasphemy, with a critic in the Augsburger Allgemeine describing Jesus as "the ugliest, most impertinent Jewish boy imaginable.

"[1] While the later Prince Regent Luitpold sided with Liebermann, the conservative MP and priest Balthasar von Daller denied him as a Jew the right to represent Jesus in this way.

Back from the Netherlands, he followed Countess von Maltzan's call to Militsch in Silesia, where he made his first commissioned work – a view of the village.

In his opinion, sooner or later Berlin would take on the role of the capital from an artistic point of view, as the largest art market was located there and he increasingly saw Munich's traditions as a burden.

In addition, he was able to feel for the first time in their circle as an accepted member of the Berlin artist community: Max Klinger, Adolph Menzel, Georg Brandes and Wilhelm Bode came and went there as well as Theodor Mommsen, Ernst Curtius and Alfred Lichtwark.

In the summer of 1886, Martha Liebermann went to Bad Homburg vor der Höhe for a cure with her daughter, which gave her husband the opportunity to study in Holland.

At the international anniversary exhibition in Munich, a critic described the painting as "the real representation of dull infirmity caused by a monotony of hard work.

[…] Peasant women in worn aprons and wooden slippers, with faces that hardly show that they were young, the features of grim old age, lie in the chamber, the beams of which are oppressively weighed down, their mechanical daily work."

Through his own efforts to save Nolde's honor, Liebermann had wanted to make his tolerance clear, but the split in the Secession movement could not be stopped.

The criticism of his leadership style grew louder until it finally came from within his own ranks: On 16 November 1911, Liebermann himself resigned as President of the Berlin Secession.

The first edition showed a lithograph by Liebermann of the masses gathered at the beginning of the war in front of the Berlin City Palace on the occasion of Wilhelm II's "party speech".

He identified with the castle peace policy of the Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, who tried to bridge internal contradictions in German society.

– Where a younger art historian Wilhelm Worringer writes from the trenches of Flanders that war decides not only for the existence of Germany, but also for the victory of Expressionism."

Instead, he dealt with illustration for the first time: In 1916 and 1917, he produced works on Goethe's novella and The Man of Fifty Years, as well as Heinrich von Kleist's Small Writings.

Liebermann took a negative view of the political changes: although he advocated the introduction of equal suffrage in Prussia and democratic-parliamentary reforms at the imperial level, for him "a whole world, albeit a rotten one", collapsed.

[...] Berlin is ragged, dirty, dark in the evening, [...] a dead city, plus soldiers selling matches or cigarettes on Friedrichstrasse or Unter den Linden, blind organ grinders in half-rotten uniforms, in one word: pitiful.

[5] In view of the need to rebuild the collapsed imperial institution, Liebermann succeeded in providing it with a democratic structure, a free educational system and, at the same time, greater public attention.

He made lithographs for Heinrich Heine's "Rabbi von Bacharach" in addition to numerous paintings of his garden and drawings in memory of fallen Jewish soldiers at the front.

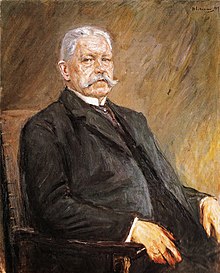

In addition to Lovis Corinth, he was also painted by the Swede Anders Zorn and the Dutchman Jan Veth, photographed by Yva and several times by Nicola Perscheid, and caricatured by Heinrich Zille, among others.

[2] Liebermann did not want to risk defending himself against the incipient change in cultural policy — as Käthe Kollwitz, Heinrich Mann or Erich Kästner did by signing the urgent appeal in June 1932.

"[5] On the advice of the Swiss banker Adolf Jöhr, he was able to deposit the 14 most important works of his art collection from May 1933 at the Kunsthaus Zürich, where Wilhelm Wartmann was director.

For example, no official representative appeared at his funeral at the Schönhauser Allee Jewish cemetery on 11 February 1935 – neither from the academy nor from the city, of which he had been an honorary citizen since 1927.