Maya (religion)

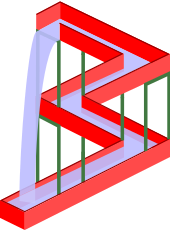

[5][6] In the Advaita Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy, māyā, "appearance",[7] is "the powerful force that creates the cosmic illusion that the phenomenal world is real".

[8] In this nondualist school, māyā at the individual level appears as the lack of knowledge (avidyā) of the real Self, Atman-Brahman, mistakenly identifying with the body-mind complex and its entanglements.

[8] In Buddhist philosophy, māyā is one of twenty subsidiary unwholesome mental factors, responsible for deceit or concealment about the illusionary nature of things.

[17][18] According to Monier Williams, māyā meant "wisdom and extraordinary power" in an earlier older language, but from the Vedic period onwards, the word came to mean "illusion, unreality, deception, fraud, trick, sorcery, witchcraft and magic".

In early Vedic usage, the term implies, states Mahony, "the wondrous and mysterious power to turn an idea into a physical reality".

[20] Jan Gonda considers the word related to mā, which means "mother",[13] as do Tracy Pintchman[21] and Adrian Snodgrass,[15] serving as an epithet for goddesses such as Lakshmi and Durga.

One titled Māyā-bheda (मायाभेद:, Discerning Illusion) includes hymns 10.177.1 through 10.177.3, as the battle unfolds between the good and the evil, as follows,[25] पतंगमक्तमसुरस्य मायया हृदा पश्यन्ति मनसा विपश्चितः । समुद्रे अन्तः कवयो वि चक्षते मरीचीनां पदमिच्छन्ति वेधसः ॥१॥ पतंगो वाचं मनसा बिभर्ति तां गन्धर्वोऽवदद्गर्भे अन्तः । तां द्योतमानां स्वर्यं मनीषामृतस्य पदे कवयो नि पान्ति ॥२॥ अपश्यं गोपामनिपद्यमानमा च परा च पथिभिश्चरन्तम् । स सध्रीचीः स विषूचीर्वसान आ वरीवर्ति भुवनेष्वन्तः ॥३॥ The wise behold with their mind in their heart the Sun, made manifest by the illusion of the Asura; The sages look into the solar orb, the ordainers desire the region of his rays.

[31] The hymns in Book 8, Chapter 10 of Atharvaveda describe the primordial woman Virāj (विराज्, chief queen) and how she willingly gave the knowledge of food, plants, agriculture, husbandry, water, prayer, knowledge, strength, inspiration, concealment, charm, virtue, vice to gods, demons, men and living creatures, despite all of them making her life miserable.

[27] Gonda suggests the central meaning of Maya in Vedic literature is, "wisdom and power enabling its possessor, or being able itself, to create, devise, contrive, effect, or do something".

[33][34] Maya stands for anything that has real, material form, human or non-human, but that does not reveal the hidden principles and implicit knowledge that creates it.

[35] The Upanishads describe the universe, and the human experience, as an interplay of Purusha (the eternal, unchanging principles, consciousness) and Prakṛti (the temporary, changing material world, nature).

[44] The basic grammar of the third and final Tamil Sangam is Tholkappiyam composed by Tholkappiyar, who according to critics is referred as Rishi Jamadagni's brother Sthiranadumagni and uncle of Parshurama.

[48] In the Tamil classics, Durga is referred to by the feminine form of the word, viz., māyol;[49] wherein she is endowed with unlimited creative energy and the great powers of Vishnu, and is hence Vishnu-Maya.

Vācaspati Miśra's commentary on the Samkhyakarika, for example, questions the Maya doctrine saying "It is not possible to say that the notion of the phenomenal world being real is false, for there is no evidence to contradict it".

[57] However, acknowledges Ballantyne,[57] Edward Gough translates the same verse in Shvetashvatara Upanishad differently, 'Let the sage know that Prakriti is Maya and that Mahesvara is the Mayin, or arch-illusionist.

[60] Illusion, state Naiyayikas, involves the projection into current cognition of predicated content from memory (a form of rushing to interpret, judge, conclude).

[72] A later Advaita scholar Prakasatman addressed this, by explaining, "Maya and Brahman together constitute the entire universe, just like two kinds of interwoven threads create a fabric.

: sgyu) is a Buddhist term translated as "pretense" or "deceit" that is identified as one of the twenty subsidiary unwholesome mental factors within the Mahayana Abhidharma teachings.

[9]Alexander Berzin explains: Pretension (sgyu) is in the categories of longing desire (raga) and naivety (which is in essence lack of experience) (moha).

Because of excessive attachment to our material gain and the respect we receive, and activated by wanting to deceive others, pretension is pretending to exhibit or claiming to have a good quality that we lack.

A man with good sight would inspect it, ponder, and carefully investigate it, and it would appear to him to be void (rittaka), hollow (tucchaka), coreless (asāraka).

[77]One sutra in the Āgama collection known as "Mahāsūtras" of the (Mūla)Sarvāstivādin tradition entitled the Māyājāla (Net of Illusion) deals especially with the theme of Maya.

This sutra only survives in Tibetan translation and compares the five aggregates with further metaphors for illusion, including: an echo, a reflection in a mirror, a mirage, sense pleasures in a dream and a madman wandering naked.

[79]Likewise, Bhikkhu Katukurunde Nyanananda Thera has written an exposition of the Kàlakàràma Sutta which features the image of a magical illusion as its central metaphor.

The Mahayana uses similar metaphors for illusion: magic, a dream, a bubble, a rainbow, lightning, the moon reflected in water, a mirage, and a city of celestial musicians.

[77] The Prajñaparamita-ratnaguna-samcayagatha (Rgs) states: This gnosis shows him all beings as like an illusion, Resembling a great crowd of people, conjured up at the crossroads, By a magician, who then cuts off many thousands of heads; He knows this whole living world as a magical creation, and yet remains without fear.

Rgs 1:19And also: Those who teach Dharma, and those who listen when it is being taught; Those who have won the fruition of a Worthy One, a Solitary Buddha, or a World Savior; And the nirvāṇa obtained by the wise and learned— All is born of illusion—so has the Tathāgata declared.

Vasubandhu's Trisvabhavanirdesa, a Mahayana Yogacara "Mind Only" text, discusses the example of the magician who makes a piece of wood appear as an elephant.

[87] In this context, the term visions denotes not only visual perceptions, but appearances perceived through all senses, including sounds, smells, tastes and tactile sensations.

The teachings of the Sikh Gurus push the idea of seva (selfless service) and simran (prayer, meditation, or remembering one's true death).