Ancient Maya art

[3] Maya art history was also spurred by the enormous increase in sculptural and ceramic imagery, due to extensive archaeological excavations, as well as to organized looting on an unprecedented scale.

Coe published a series of books offering pictures and interpretations of unknown Maya vases, with the Popol Vuh Twin myth for an explanatory model.

[4] In 1981, Robicsek and Hales added an inventory and classification of Maya vases painted in codex style,[5] thereby revealing even more of a hitherto barely known spiritual world.

[12] The layout of the Maya towns and cities, and more particularly of the ceremonial centers where the royal families and courtiers resided, is characterized by the rhythm of immense horizontal stucco floors of plazas often located at various levels, connected by broad and often steep stairs, and surmounted by temple pyramids.

Outside the ceremonial center (especially in the southern area sometimes resembling an acropolis) were the structures of lesser nobles, smaller temples, and individual shrines, surrounded by the wards of the commoners.

The main Preclassic sculptural style from the Maya area is that of Izapa, a large site on the Pacific coast where many stelas and (frog-shaped) altars were found showing motifs also present in Olmec art.

The most important Classic examples consist of intricately worked lintels, mostly from the main Tikal pyramid sanctuaries,[25] with one specimen from nearby El Zotz.

At least since Late Preclassic times, modeled and painted stucco plaster covered the floors and buildings of the town centers and provided the setting for their stone sculptures.

Often, large mask panels with the plastered heads of deities in high relief (particularly those of sun, rain, and earth) are found attached to the sloping retaining walls of temple platforms flanking stairs (e.g., Kohunlich).

The stuccoed friezes, walls, piers, and roof combs of the Late Preclassic and Classic periods show varying and sometimes symbolically complicated decorative programs.

[27] Similarly, a Classic palace frieze in Acanceh is divided into panels holding different animal figures[28] reminiscent of wayob, while a wall in Tonina has lozenge-shaped fields suggesting a scaffold and presenting continuous narrative scenes that relate to human sacrifice.

[29] Plastered roof combs are similar to some of the friezes above in that they usually show large representations of rulers, who may again be seated on a symbolic mountain, and also, as on Palenque's Temple of the Sun, set within a cosmological framework.

Although, due to the humid climate of Central America, relatively few Maya paintings have survived to the present day integrally, important remnants have been found in nearly all major court residences.

Mural paintings may show more or less repetitive motifs, such as the subtly varied flower symbols on walls of House E of the Palenque Palace; scenes of daily life, as in one of the buildings surrounding the central square of Calakmul and in a palace of Chilonche; or ritual scenes involving deities, as in the Post-Classic temple murals of Yucatán's and Belize's east coast (Tancah, Tulum, Santa Rita).

The colourful Bonampak murals, for example, dating from 790 AD, and extending over the walls and vaults of three adjacent rooms, show spectacular scenes of nobility, battle and sacrifice, as well as a group of ritual impersonators in the midst of a file of musicians.

[32] At San Bartolo, murals dating from 100 BCE relate to the myths of the Maya maize god and the hero twin Hunahpu, and depict a double inthronization; antedating the Classic Period by several centuries, the style is already fully developed, with colours being subtle and muted as compared to those of Bonampak or Calakmul.

A bright turquoise blue colour—'Maya Blue'—has survived through the centuries due to its unique chemical characteristics; this color is present in Bonampak, Cacaxtla, Jaina, El Tajín, and even in some Colonial convents.

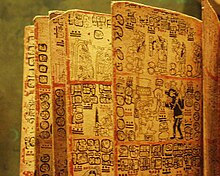

The books were folded and consisted of bark paper or leather leaves with an adhesive stucco layer on which to write; they were protected by jaguar skin covers and, perhaps, wooden boards.

A fourth book, the Grolier, is Maya-Toltec rather than Maya and lacks hieroglyphic texts; fragmentary and of very poor draughtsmanship, it shows many anomalies, reason for which its authenticity has long remained in doubt.

[9] Sculptors at Copan and Quirigua have consequently felt free to convert hieroglyphic elements and calendrical signs into animated, dramatic miniature scenes ('full figure glyphs').

[39] Unlike utility ceramics found in such large numbers among the debris of archaeological sites, most of the decorated pottery (cylinder vessels, lidded dishes, tripod plates, vases, bowls) once was 'social currency' among the Maya nobility, and, preserved as heirlooms, also accompanied the nobles into their graves.

[40] The aristocratic tradition of gift-giving feasts[41] and ceremonial visits, and the emulation that inevitably went with these exchanges, goes a long way towards explaining the high level of artistry reached in Classical times.

'[43] Vase decoration shows great variation, including palace scenes, courtly ritual, mythology, divinatory glyphs, and even dynastical texts taken from chronicles, and plays a major role in reconstructing Classical Maya life and beliefs.

Ceramic scenes and texts painted in black and red on a white underground, the equivalents of pages from the lost folding books, are referred to as being in 'Codex Style' (e.g., the so-called Princeton Vase).

Best known are the profusely decorated Classic burners from the kingdom of Palenque, which have the modeled face of a deity or of a king attached to an elongated hollow tube.

It is remarkable that the Maya, who had no metal tools, created many objects from a very hard and dense material, jade (jadeite), particularly all sorts of (royal) dress elements, such as belt plaques, Celts, ear spools, pendants, and also masks.

A collection of small and modified, tubular bones from an 8th-century royal burial under Tikal Temple I contains some of the most subtle engravings known from the Maya, including several scenes with the Tonsured maize god in a canoe.

[50] Textiles from the Classic period, made of cotton, have not survived, but Maya art provides detailed information about their appearance and, to a lesser extent, their social function.

Noblewomen usually wore long dresses, noblemen girdles and breechcloths, leaving legs and upper body more or less bare, unless jackets or mantles were worn.

The Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin holds a broad selection of Maya artifacts, including an incised Early-Classic vase showing a king lying in state and awaiting post-mortem transformation.