Maya codices

[4] Our knowledge of ancient Maya thought must represent only a tiny fraction of the whole picture, for of the thousands of books in which the full extent of their learning and ritual was recorded, only four have survived to modern times (as though all that posterity knew of ourselves were to be based upon three prayer books and Pilgrim's Progress).Before the arrival of Spanish conquistadors, the Aztecs eradicated many Mayan works and sought to depict themselves as the true rulers through a fake history and newly written texts.

There were many books in existence at the time of the Spanish conquest of Yucatán in the 16th century; most were destroyed by the Catholic priests.

[8] Bishop de Landa hosted a mass book burning in the town of Maní in the Yucatán peninsula.

[9] De Landa wrote: We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.Such codices were the primary written records of Maya civilization, together with the many inscriptions on stone monuments and stelae that survived.

Their range of subject matter in all likelihood embraced more topics than those recorded in stone and buildings, and was more like what is found on painted ceramics (the so-called 'ceramic codex').

Alonso de Zorita wrote that in 1540 he saw numerous such books in the Guatemalan highlands that "recorded their history for more than eight hundred years back, and that were interpreted for me by very ancient Indians".

The only exact replica, including the huun, made by a German artist is displayed at the Museo Nacional de Arqueología in Guatemala City, since October 2007.

The glyphs show roughly 40 times in the text, making eclipses a major focus of the Dresden Codex.

[28] Extremadura is the province from which Francisco de Montejo and many of his conquistadors came,[25] as did Hernán Cortés, the conqueror of Mexico.

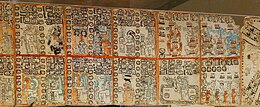

[27] The content of the Madrid Codex mainly consists of almanacs and horoscopes that were used to help Maya priests in the performance of their ceremonies and divinatory rituals.

The codex also contains astronomical tables, although fewer than the other two generally accepted surviving Maya codices.

Other scholars have expressed a differing opinion, noting that the codex is similar in style to murals found at Chichen Itza, Mayapan and sites on the east coast such as Santa Rita, Tancah and Tulum.

The original drawing is now lost, but a copy survives among some of Kingsborough's unpublished proof sheets, held in collection at the Newberry Library, Chicago.

[34] Although occasionally referred to over the next quarter-century, its permanent rediscovery is attributed to the French orientalist Léon de Rosny, who in 1859 recovered the codex from a basket of old papers sequestered in a chimney corner at the Bibliothèque Nationale where it had lain discarded and apparently forgotten.

[42] Códice Maya de México: Understanding the Oldest Surviving Book of the Americas was published to accompany an exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum October 18, 2022, to January 15, 2023.

Archaeological excavations of Maya sites have turned up a number of rectangular lumps of plaster and paint flakes, most commonly in elite tombs.

A few of the more coherent of these lumps have been preserved, with the slim hope that some technique to be developed by future generations of archaeologists may be able to recover some information from these remains of ancient pages.

The oldest Maya codices known have been found by archaeologists as mortuary offerings with burials in excavations in Uaxactun, Guaytán in San Agustín Acasaguastlán, and Nebaj in El Quiché, Guatemala, at Altun Ha in Belize and at Copán in Honduras.

[44] Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, a Soviet linguist, epigrapher and ethnographer played a pivotal role in the decipherment of the Maya script.