Maya script

The earliest inscriptions found which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd century BCE in San Bartolo, Guatemala.

Mayan writing consisted of a relatively elaborate and complex set of glyphs, which were laboriously painted on ceramics, walls and bark-paper codices, carved in wood or stone, and molded in stucco.

As of 2008[update], the sound of about 80% of Maya writing could be read and the meaning of about 60% could be understood with varying degrees of certainty, enough to give a comprehensive idea of its structure.

Glyphs used as syllabograms were originally logograms for single-syllable words, usually those that ended in a vowel or in a weak consonant such as y, w, h, or glottal stop.

However, the language changed over 1500 years, and there were dialectal differences as well, which are reflected in the script, as seen next for the verb "(s)he sat" (⟨h⟩ is an infix in the root chum for the passive voice):[8] An "emblem glyph" is a kind of royal title.

It consists of a place name followed by the word ajaw, a Classic Maya term for "lord" with an unclear but well-attested etymology.

Marcus' research assumed that the emblem glyphs were distributed in a pattern of relative site importance depending on broadness of distribution, roughly broken down as follows: Primary regional centers (capitals) (Tikal, Calakmul, and other "superpowers") were generally first in the region to acquire a unique emblem glyph(s).

[11] This model was largely unchallenged for over a decade until Mathews and Justeson,[12] as well as Houston,[13] argued once again that the "emblem glyphs" were the titles of Maya rulers with some geographical association.

Moreover, the authors also highlighted the cases when the "titles of origin" and the "emblem glyphs" did not overlap, building upon Houston's earlier research.

[14] Houston noticed that the establishment and spread of the Tikal-originated dynasty in the Petexbatun region was accompanied by the proliferation of rulers using the Tikal "emblem glyph" placing political and dynastic ascendancy above the current seats of rulership.

Before the arrival of Spanish conquistadors, the Aztecs destroyed many Mayan works and sought to depict themselves as the true rulers through a fake history and newly written texts.

[22] Most surviving texts are found on pottery recovered from Maya tombs, or from monuments and stelae erected in sites which were abandoned or buried before the arrival of the Spanish.

In the 1930s, Benjamin Whorf wrote a number of published and unpublished essays, proposing to identify phonetic elements within the writing system.

[24] Napoleon Cordy also made some notable contributions in the 1930s and 1940s to the early study and decipherment of Maya script, also arguing for some share of phonetic signs in 1946.

Since the early 1980s scholars have demonstrated that most of the previously unknown symbols form a syllabary, and progress in reading the Maya writing has advanced rapidly since.

However, in the 1960s, more came to see the syllabic approach as potentially fruitful, and possible phonetic readings for symbols whose general meaning was understood from context began to develop.

[29] For example, Coe (1992, p. 164) says "the major reason was that almost the entire Mayanist field was in willing thrall to one very dominant scholar, Eric Thompson".

An Englishman by birth, Eric Thompson, after learning about the results of the work of a young Soviet scientist, immediately realized 'who got the victory'.

"[30] In 1959, examining what she called "a peculiar pattern of dates" on stone monument inscriptions at the Classic Maya site of Piedras Negras, Russian-American scholar Tatiana Proskouriakoff determined that these represented events in the lifespan of an individual, rather than relating to religion, astronomy, or prophecy, as held by the "old school" exemplified by Thompson.

However, further progress was made during the 1960s and 1970s, using a multitude of approaches including pattern analysis, de Landa's "alphabet", Knorozov's breakthroughs, and others.

In the story of Maya decipherment, the work of archaeologists, art historians, epigraphers, linguists, and anthropologists cannot be separated.

They stood revealed as a people with a history like that of all other human societies: full of wars, dynastic struggles, shifting political alliances, complex religious and artistic systems, expressions of personal property and ownership and the like.

It did not directly attack the methodology or results of decipherment, but instead contended that the ancient Maya texts had indeed been read but were "epiphenomenal".

This argument was extended from a populist perspective to say that the deciphered texts tell only about the concerns and beliefs of the society's elite, and not about the ordinary Maya.

In opposition to this idea, Michael Coe described "epiphenomenal" as "a ten penny word meaning that Maya writing is only of marginal application since it is secondary to those more primary institutions—economics and society—so well studied by the dirt archaeologists.

"[35] Linda Schele noted following the conference that this is like saying that the inscriptions of ancient Egypt—or the writings of Greek philosophers or historians—do not reveal anything important about their cultures.

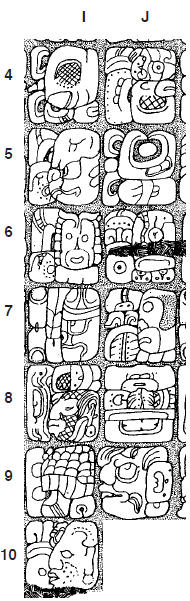

[38] Tomb of Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal: Text: Yak’aw ʔuk’uhul pik juʔn winaak pixoʔm ʔusak hunal ʔuʔh Yax K’ahk’ K’uh(?)

Various works have recently been both transliterated and created into the script, notably the transcription of the Popol Vuh, a record of Kʼicheʼ religion, in 2018.

[citation needed] Another example is the sculpting and writing of a modern stele placed at Iximche in 2012, describing the full historical record of the site dating back to the beginning of the Mayan long count.

[40] The Maya script can be represented as a custom downloadable primer's font [41] but has yet to be formally introduced into Unicode standards.