Meconium aspiration syndrome

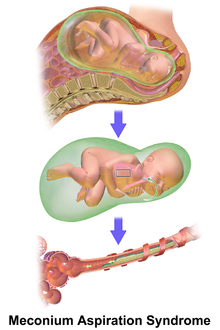

It describes the spectrum of disorders and pathophysiology of newborns born in meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) and have meconium within their lungs.

[5] For the meconium within the amniotic fluid to successfully cause MAS, it has to enter the respiratory system during the period when the fluid-filled lungs transition into an air-filled organ capable of gas exchange.

[1] The main theories of meconium passage into amniotic fluid are caused by fetal maturity or from foetal stress as a result of hypoxia or infection.

[3] Foetal hypoxic stress during parturition can stimulate colonic activity, by enhancing intestinal peristalsis and relaxing the anal sphincter, which results in the passage of meconium.

The early control mechanisms of the anal sphincter are not well understood, however there is evidence that the foetus does defecate routinely into the amniotic cavity even in the absence of distress.

Once within the terminal bronchioles and alveoli, the meconium triggers inflammation, pulmonary edema, vasoconstriction, bronchoconstriction, collapse of airways and inactivation of surfactant.

[10][11] The lung areas which do not or only partially participate in ventilation, because of obstruction and/or destruction, will become hypoxic and an inflammatory response may consequently occur.

A microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity (MIAC) is more common in patients with MSAF and this could ultimately lead to an intra-amniotic inflammatory response.

Therefore, these aforementioned mediators within the amniotic fluid during MIAC and intra-amniotic infection could, when aspirated in utero, induce lung inflammation within the foetus.

[12] Meconium has a complex chemical composition, so it is difficult to identify a single agent responsible for the several diseases that arise.

Meconium perhaps leads to chemical pneumonitis as it is a potent activator of inflammatory mediators which include cytokines, complement, prostaglandins and reactive oxygen species.

[5] Meconium is a source of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukins (IL-1, IL-6, IL-8), and mediators produced by neutrophils, macrophages and epithelial cells that may injure the lung tissue directly or indirectly.

[11] Recently, it has been hypothesised that meconium is a potent activator of toll-like receptor (TLRs) and complement, key mediators in inflammation, and may thus contribute to the inflammatory response in MAS.

[1][5] Meconium contains high amounts of phospholipase A2 (PLA2), a potent proinflammatory enzyme, which may directly (or through the stimulation of arachidonic acid) lead to surfactant dysfunction, lung epithelium destruction, tissue necrosis and an increase in apoptosis.

[1][11] Meconium can also activate the coagulation cascade, production of platelet-activating factor (PAF) and other vasoactive substances that may lead to destruction of capillary endothelium and basement membranes.

A combination of hypoxia, pulmonary vasoconstriction and ventilation/perfusion mismatch can trigger PPHN, depending on the concentration of meconium within the respiratory tract.

[1] Respiratory distress in an infant born through the darkly coloured MSAF as well as meconium obstructing the airways is usually sufficient to diagnose MAS.

It is common for sedation and muscle relaxants to be used to optimise ventilation and minimise the risk of pneumothorax associated with dyssynchronous breathing.

[18] Inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) acts on vascular smooth muscle causing selective pulmonary vasodilation.

This is ideal in the treatment of PPHN as it causes vasodilation within ventilated areas of the lung thus, decreasing the ventilation-perfusion mismatch and thereby, improves oxygenation.

Treatment utilising iNO decreases the need for ECMO and mortality in newborns with hypoxic respiratory failure and PPHN as a result of MAS.

Additionally, methylxanthines decreases the concentrations of calcium, acetylcholine and monoamines, this controls the release of various mediators of inflammation and bronchoconstriction, including prostaglandins.

[24] Arachidonic acid is metabolised, via cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase, to various substances including prostaglandins and leukotrienes, which exhibit potent pro-inflammatory and vasoactive effects.

However, there are risks as a large volume of fluid instillation to the lung of a newborn can be dangerous (particularly in cases of severe MAS with pulmonary hypertension) as it can exacerbate hypoxia and lead to mortality.

Thus, to prevent newborns, who were born through MSAF, from developing MAS, suctioning of the oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal area before delivery of the shoulders followed by tracheal aspiration was utilised for 20 years.

This treatment was believed to be effective as it was reported to significantly decrease the incidence of MAS compared to those newborns born through MSAF who were not treated.

[26] This claim was later disproved and future studies concluded that oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal suctioning, before delivery of the shoulders in infants born through MSAF, does not prevent MAS or its complications.

The UK National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Guidelines recommend against the use of amnioinfusion in women with MSAF.

[22] Additionally, there is still research being conducted on whether intubation and suctioning of meconium in newborns with MAS is beneficial, harmful or is simply a redundant and outdated treatment.