Medieval Christian views on Muhammad

[4][5][6][7][8] Various Western and Byzantine Christian thinkers[5][6][7][9] considered Muhammad to be a perverted,[5][7] deplorable man,[5][7] a false prophet,[5][6][7][8] and even the Antichrist,[5][6] as he was frequently seen in Christendom as a heretic or possessed by demons.

In the anti-Jewish polemic the Teaching of Jacob, a dialogue between a recent Christian convert and several Jews, one participant writes that his brother "wrote to [him] saying that a deceiving prophet has appeared amidst the Saracens".

[17][18] In the 8th century John of Damascus, a Syrian monk, Christian theologian, and apologist that lived under the Umayyad Caliphate, reported in his heresiological treatise De Haeresibus ("Concerning Heresy") the Islamic denial of Jesus' crucifixion and his alleged substitution on the cross, attributing the origin of these doctrines to Muhammad himself:[19]: 106–107 [20]: 115–116 And the Jews, having themselves violated the Law, wanted to crucify him, but having arrested him they crucified his shadow.

[27] According to one version after falling into a drunken stupor he had been eaten by a herd of swine, and this was ascribed as the reason why Muslims proscribed consumption of alcohol and pork.

It also ascribed the Muslim holiday of Friday "dies Veneris" (day of Venus), as against the Jewish (Saturday) and the Christian (Sunday), to his followers' depravity as reflected in their multiplicity of wives.

[27] A highly negative depiction of Muhammad as a heretic, false prophet, renegade cardinal or founder of a violent religion also found its way into many other works of European literature, such as the chansons de geste, William Langland's Piers Plowman, and John Lydgate's The Fall of the Princes.

[1] The thirteenth century Golden Legend, a best-seller in its day containing a collection of hagiographies, describes "Magometh, Mahumeth (Mahomet, Muhammad)" as "a false prophet and sorcerer", detailing his early life and travels as a merchant through his marriage to the widow, Khadija and goes on to suggest his "visions" came as a result of epileptic seizures and the interventions of a renegade Nestorian monk named Sergius.

In the same vein, the definition of "Saracen" in Raymond of Penyafort's Summa de Poenitentia starts by describing the Muslims but ends by including every person who is neither a Christian nor a Jew.

[1] In medieval romances such as the French Arthurian cycle, pagans such as the ancient Britons or the inhabitants of "Sarras" before the conversion of King Evelake, who presumably lived well before the birth of Muhammad, are often described as worshipping the same array of gods and as identical to the imagined (Termagant-worshipping) Muslims in every respect.

In describing the travels of Joseph of Arimathea, keeper of the Holy Grail, the author says that most residents of the Middle East were pagans until the coming of Muhammad, who is shown as a true prophet sent by God to bring Christianity to the region.

[32] In Inferno, the first part of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Muhammad is placed in Malebolge, the eighth circle of hell, designed for those who have committed fraud; specifically, he is placed in the ninth bolgia (ditch) among the sowers of discord and schism.

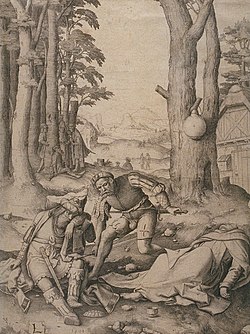

Muhammad is portrayed as split in half, with his entrails hanging out, representing his status as a heresiarch (Inferno 28): This graphic scene is frequently shown in illustrations of the Divine Comedy: Muhammad is represented in a 15th-century fresco Last Judgment by Giovanni da Modena and drawing on Dante, in the San Petronio Basilica in Bologna,[34] as well as in artwork by Salvador Dalí, Auguste Rodin, William Blake, and Gustave Doré.

"[36] One common allegation laid against Muhammad was that he was an impostor who, in order to satisfy his ambition and his lust, propagated religious teachings that he knew to be false.

Dante lived during the eighth and ninth Crusades and would have been brought up around the idea that it is righteous to war against Muslims—namely, against the Hafsid dynasty, the Sunni Muslims who ruled the Medieval province Ifriqiya, an area on the northern coast of Africa.

[41] When the Knights Templar were being tried for heresy reference was often made to their worship of a demon Baphomet, which was notable by implication for its similarity to the common rendition of Muhammad's name used by Christian writers of the time, Mahomet.

[42] All these and other variations on the theme were all set in the "temper of the times" of what was seen as a Muslim-Christian conflict as Medieval Europe was building a concept of "the great enemy" in the wake of the quickfire success of the early Muslim conquests shortly after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, as well as the lack of real information in the West of the mysterious East.

[37] In the Heldenbuch-Prosa, a prose preface to the manuscript Heldenbuch of Diebolt von Hanowe from 1480, the demon Machmet appears to the mother of the Germanic hero Dietrich and builds "Bern" (Verona) in three days.

Criticism by Christians [...] was voiced soon after the advent of Islam starting with St. John of Damascus in the late seventh century, who wrote of "the false prophet", Muhammad.

In the twelfth century, Peter the Venerable [...] who had the Koran translated into Latin, regarded Islam as a Christian heresy and Muhammad as a sexually self-indulgent and a murderer.