Medieval Japanese literature

Japanese Buddhism also underwent a reform during this period, with several important new sects being established, with the founders of these sects—most famously Dōgen, Shinran, and Nichiren—writing numerous treatises expounding their interpretation of Buddhist doctrine.

Folk songs and religious and secular tales were collects in a number of anthologies, and travel literature, which had been growing in popularity throughout the medieval period, became more and more commonplace.

[1] Later developments include en (艶, literally "lustre" or "polish"), hie (ひえ) and sabi (roughly "stillness" or "attenuation"), connecting to the literature of Japan's early modern period.

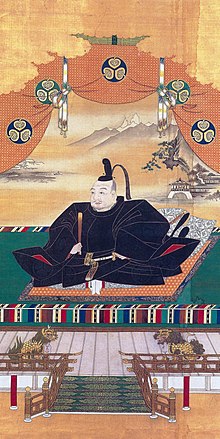

[1] Medieval Japanese literature is most often associated with members of the warrior class, religious figures and hermits (隠者 inja), but the nobility maintained a degree of their former prestige and occupied an important position in literary circles.

[1] This was especially true in the early middle ages (i.e., the Kamakura period), when court literature still carried the high pedigree of earlier eras, while monks, recluses and warriors took an increasingly prominent role in later centuries.

[1] However, with the failure of the Jōkyū rebellion and Emperor Go-Toba's exile to Oki Island, the court lost almost all power, and the nobility became increasingly nostalgic, with the aristocratic literature of the later Kamakura period reflecting this.

[6] This flourishing was characteristic of the first three or four decades of the Kamakura period, but following the Jōkyū rebellion and the exile of Go-Toba, the great patron of waka, the genre went into decline.

[6] Overall, while poetic composition at court floundered during the Kamakura period, the courtiers continued the act of collecting and categorizing the poems of earlier eras, with such compilations as the Fuboku Waka-shō [ja] and the Mandai Wakashū (万代和歌集) epitomizing this nostalgic tendency.

[6] This work was compiled on the order of Emperor Kameyama's mother Ōmiya-in (the daughter of Saionji Saneuji), and shows not only the high place courtly fiction had attained in the tastes of the aristocracy by this time, but the reflective/critical bent with which the genre had come to be addressed in its final years.

They were composed in wakan konkō-bun, a form of literary Japanese that combined the yamato-kotoba of the court romances with Chinese elements, and described fierce battles in the style of epic poetry.

[6] The authors of these works are largely unknown, but they were frequently adapted to meet the tastes of their audiences, with court literati, Buddhist hermits, and artists of the lower classes all likely having a hand in their formation.

[6] Other works targeted at members of the newly ascendant warrior class had a stronger emphasis on disciplined learning and Confucianism, as exemplified in the Jikkinshō [ja].

[6] Of particular note are the works of monk and compiler Mujū Dōgyō, such as Shaseki-shū and Zōdan-shū (雑談集), which mix fascinating anecdotes of everyday individuals in with Buddhist sermons.

[9] These include: Many of these Buddhist writings, or hōgo, expound on deep philosophical principles, or explain the basics of Buddhism in a simple manner that could easily be digested by the uneducated masses.

[9] The noh theatre came under the protection and sponsorship of the warrior class, with Kan'ami and his son Zeami bringing it to new artistic heights, while Nijō Yoshimoto and lower-class renga (linked verse) masters formalized and popularized that form.

[9] Noh and its comic counterpart kyōgen is the standard example of this phenomenon, but renga had haikai, waka had its kyōka and kanshi (poetry in Classical Chinese) had its kyōshi.

[9] Ichiko notes that while this reverence for the literature of the past was important, it is also a highly noteworthy characteristic of this period that new genres and forms, unlike those of earlier eras, prevailed.

[12] The founder of the lineage was Yishan Yining (Issan Ichinei in Japanese), an immigrant from Yuan China,[12] and his disciples included Kokan Shiren,[13] Sesson Yūbai,[14] Musō Soseki[14] and others;[14] these monks planted the seeds of the Five Mountains literary tradition.

[13] Ichiko remarks that while Chūgan Engetsu also created excellent writings at this time, it was Musō's disciples Gidō Shūshin and Zekkai Chūshin [ja] who brought the literature of the Five Mountains to its zenith.

[13] Some haikai, according to Ichiko, ventured too far into absurdity, but they tapped into the popular spirit of the Japanese masses, and laid the groundwork for the major developments of the form in the early modern period.

[13] Some of these works (such as Aki no Yo no Naga Monogatari) described monastic life, some (such as Sannin Hōshi) expounded the virtues of seclusion, some (such as Kumano no Honji) elaborate on the origins of temples and shrines in light of the concept of honji suijaku ("original substances manifest their traces", the concept that the gods of Shinto are Japanese manifestations of Buddhist deities[19]), and some (such as Eshin-sōzu Monogatari) are biographies of Buddhist saints.

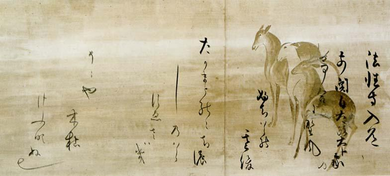

[13] A number of works, called irui-mono (異類物) or gijin-shōsetsu (擬人小説, "personification novels"), include anthropomorphized plants and animals, and these appear to have been very popular among readers of the day.

[20] Similarly to the Gukanshō, it includes not only a dry narration of historical events but a degree of interpretation on the part of its author, with the primary motive being to demonstrate how the "correct" succession has followed down to the present day.

[21] Ichiko notes that while each of these works have unique characteristics, they tend to follow a formula, recounting the (mostly small-scale) real-world skirmishes that inspired them in a blasé fashion and lacking the masterful quality of the Heike or Taiheiki.

[21] Going into the Muromachi period, works such as the Sangoku Denki (三国伝記) and Gentō (玄棟) and Ichijō Kaneyoshi's Tōsai Zuihitsu [ja] are examples of setsuwa-type literature.

[21] A variant on the setsuwa anthology that developed in this period is represented by such works as Shiteki Mondō (塵滴問答) and Hachiman Gutōkun [ja], which take the form of dialogues that recount the origins of things.

[21] Some warriors of the armies sweeping the country toward the end of the medieval period also left travel journals, including those of Hosokawa Yūsai and Kinoshita Chōshōshi [ja].

[21] The works of Shinkei, including Sasamegoto (ささめごと), Hitorigoto (ひとりごと) and Oi no Kurigoto (老のくりごと) are examples of such literary essays, and are noted for their deep grasp of the aesthetic principles of yūgen, en, hie, sabi, and so on.

[21] In the 14th and 15th centuries, Kan'ami and his son Zeami, artists in the Yamato sarugaku, tradition created noh (also called nōgaku), which drew on and superseded these forerunner genres.

[21] According to Ichiko, while noh consists of song, dance, and instrumentals, is more "classical" and "symbolic", and is based on the ideal of yūgen, kyōgen relies more on spoken dialogue and movement, is more "contemporary" and "realistic", and emphasizes satire and humour.