Medium wave

During the daytime, reception is usually limited to more local stations, though this is dependent on the signal conditions and quality of radio receiver used.

Strong transmitters cover larger areas than on the FM broadcast band but require more energy and longer antennas.

Wavelengths in this band are long enough that radio waves are not blocked by buildings and hills and can propagate beyond the horizon following the curvature of the Earth; this is called the groundwave.

Medium waves can also reflect off charged particle layers in the ionosphere and return to Earth at much greater distances; this is called the skywave.

At night, especially in winter months and at times of low solar activity, the lower ionospheric D layer virtually disappears.

When this happens, MW radio waves can easily be received many hundreds or even thousands of miles away as the signal will be reflected by the higher F layer.

Early transmitters were technically crude and virtually impossible to set accurately on their intended frequency and if (as frequently happened) two (or more) stations in the same part of the country broadcast simultaneously the resultant interference meant that usually neither could be heard clearly.

The Commerce Department rarely intervened in such cases but left it up to stations to enter into voluntary timesharing agreements amongst themselves.

[7] Most United States AM radio stations are required by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to shut down, reduce power, or employ a directional antenna array at night in order to avoid interference with each other due to night-time only long-distance skywave propagation (sometimes loosely called ‘skip’).

Among those are Germany,[8] France, Russia, Poland, Sweden, the Benelux, Austria, Switzerland, Slovenia and most of the Balkans.

This also applies to the ex-offshore pioneer Radio Caroline that now has a licence to use 648 kHz, which was used by the BBC World Service over decades.

As the MW band is thinning out, many local stations from the remaining countries as well as from North Africa and the Middle East can now be received all over Europe, but often only weak with much interference.

International medium wave broadcasting in Europe has decreased markedly with the end of the Cold War and the increased availability of satellite and Internet TV and radio, although the cross-border reception of neighbouring countries' broadcasts by expatriates and other interested listeners still takes place.

In the late 20th century, overcrowding on the Medium wave band was a serious problem in parts of Europe contributing to the early adoption of VHF FM broadcasting by many stations (particularly in Germany).

C-QUAM is the official standard in the United States as well as other countries, but receivers that implement the technology are no longer readily available to consumers.

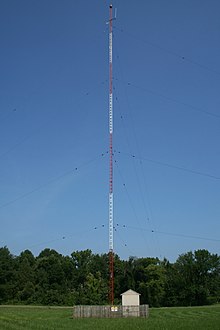

Stations broadcasting with low power can use masts with heights of a quarter-wavelength (about 310 millivolts per meter using one kilowatt at one kilometre) to 5/8 wavelength (225 electrical degrees; about 440 millivolts per meter using one kilowatt at one kilometre), while high power stations mostly use half-wavelength to 5/9 wavelength.

The usage of masts taller than 5/9 wavelength (200 electrical degrees; about 410 millivolts per meter using one kilowatt at one kilometre) with high power gives a poor vertical radiation pattern, and 195 electrical degrees (about 400 millivolts per meter using one kilowatt at one kilometre) is generally considered ideal in these cases.

Another possibility consists of feeding the mast or the tower by cables running from the tuning unit to the guys or crossbars at a certain height.

A popular choice for lower-powered stations is the umbrella antenna, which needs only one mast one-tenth wavelength or less in height.

At the top of the mast, radial top-load wires are connected (usually about six) which slope downwards at an angle of 40–45 degrees as far as about one-third of the total height, where they are terminated in insulators and thence outwards to ground anchors.

For reception at frequencies below 1.6 MHz, which includes long and medium waves, loop antennas are popular because of their ability to reject locally generated noise.

The high permeability ferrite core allows it to be compact enough to be enclosed inside the radio's case and still have adequate sensitivity.