Meiji Restoration

A year later Perry returned in threatening large warships with the aspiration of concluding a treaty that would open up Japanese ports for trade.

[1] Perry concluded the treaty that would open up two Japanese ports (Shimoda and Hakodate) only for material support, such as firewood, water, food, and coal for U.S. ships.

The word "Meiji" means "enlightened rule" and the goal was to combine "modern advances" with traditional "eastern" values (和魂洋才, Wakonyosai).

[2] The main leaders of this were Itō Hirobumi, Matsukata Masayoshi, Kido Takayoshi, Itagaki Taisuke, Yamagata Aritomo, Mori Arinori, Ōkubo Toshimichi, and Yamaguchi Naoyoshi.

The foundation of the Meiji Restoration was the 1866 Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance between Saigō Takamori and Kido Takayoshi, leaders of the reformist elements in the Satsuma and Chōshū Domains at the southwestern end of the Japanese archipelago.

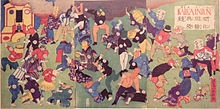

It is desirable that the representatives of the treaty powers recognize this announcement.Shortly thereafter in January 1868, the Boshin War started with the Battle of Toba–Fushimi in which Chōshū and Satsuma's forces defeated the ex-shōgun's army.

[10] Subsequently, De Graeff van Polsbroek assisted the emperor and the government in their negotiations with representatives of the major European powers.

Other daimyō were subsequently persuaded to do so, thus creating a central government in Japan which exercised direct power through the entire "realm".

The defeat of the armies of the former shōgun (led by Enomoto Takeaki and Hijikata Toshizō) marked the final end of the Tokugawa shogunate, with the Emperor's power fully restored.

[13] Emperor Meiji announced in his 1868 Charter Oath that "Knowledge shall be sought all over the world, and thereby the foundations of imperial rule shall be strengthened.

"[14] Under the leadership of Mori Arinori, a group of prominent Japanese intellectuals went on to form the Meiji Six Society in 1873 to continue to "promote civilization and enlightenment" through modern ethics and ideas.

One of the primary differences between the samurai and peasant classes was the right to bear arms; this ancient privilege was suddenly extended to every male in the nation.

Despite the bakufu's best efforts to freeze the four classes of society in place, during their rule villagers had begun to lease land out to other farmers, becoming rich in the process.

Besides drastic changes to the social structure of Japan, in an attempt to create a strong centralized state defining its national identity, the government established a dominant national dialect, called "standard language" (標準語, hyōjungo), that replaced local and regional dialects and was based on the patterns of Tokyo's samurai classes.

By the end of the Meiji period, attendance in public schools was widespread, increasing the availability of skilled workers and contributing to the industrial growth of Japan.

Many people believed it was essential for Japan to acquire western "spirit" in order to become a great nation with strong trade routes and military strength.

There were a few factories set up using imported technologies in the 1860s, principally by Westerners in the international settlements of Yokohama and Kobe, and some local lords, but these had relatively small impacts.

[21] Since the new sectors of the economy could not be heavily taxed, the costs of industrialisation and necessary investments in modernisation heavily fell on the peasant farmers, who paid extremely high land tax rates (about 30 percent of harvests) as compared to the rest of the world (double to seven times of European countries by net agricultural output).

[22] During the Meiji period, powers such as Europe and the United States helped transform Japan and made them realize a change needed to take place.

Because of Japan's leaders taking control and adapting Western techniques it has remained one of the world's largest industrial nations.

Consequently, domestic companies became consumers of Western technology and applied it to produce items that would be sold cheaply in the international market.

Since the feudal system was abolished and the fiefs (han) theoretically reverting to the emperor, the national government saw no further use for the upkeep of these now obsolete castles.

[25] Some however were explicitly saved from destruction by interventions from various persons and parties such as politicians, government and military officials, experts, historians, and locals who feared a loss of their cultural heritage.

During the Meiji restoration's shinbutsu bunri, tens of thousands of Japanese Buddhist religious idols and temples were smashed and destroyed.

In the blood tax riots, the Meiji government put down revolts by Japanese samurai angry that the traditional untouchable status of burakumin was legally revoked.