Meiji era

As a result of such wholesale adoption of radically different ideas, the changes to Japan were profound, and affected its social structure, internal politics, economy, military, and foreign relations.

The first reform was the promulgation of the Five Charter Oath in 1868, a general statement of the aims of the Meiji leaders to boost morale and win financial support for the new government.

Its five provisions consisted of: Implicit in the Charter Oath was an end to exclusive political rule by the bakufu (a shōgun's direct administration including officers), and a move toward more democratic participation in government.

Private ownership was legalized, deeds were issued, and lands were assessed at fair market value with taxes paid in cash rather than in kind as in pre-Meiji days and at slightly lower rates.

Dissatisfied with the pace of reform after having rejoined the Council of State in 1875, Itagaki organized his followers and other democratic proponents into the nationwide Aikokusha (Society of Patriots) to push for representative government in 1878.

The Osaka Conference in 1875 resulted in the reorganization of government with an independent judiciary and an appointed Chamber of Elders (genrōin) tasked with reviewing proposals for a legislature.

To further strengthen the authority of the State, the Supreme War Council was established under the leadership of Yamagata Aritomo (1838–1922), a Chōshū native who has been credited with the founding of the modern Japanese army and was to become the first constitutional Prime Minister.

It provided for the Imperial Diet (Teikoku Gikai), composed of a popularly elected House of Representatives with a very limited franchise of male citizens who were over twenty-five years of age and paid fifteen yen in national taxes (approximately 1% of the population).

Between 1891 and 1895, Ito served as Prime Minister with a cabinet composed mostly of genrō who wanted to establish a government party to control the House of Representatives.

Five hundred people from the old court nobility, former daimyo, and samurai who had provided valuable service to the Emperor were organized into a new peerage, the Kazoku, consisting of five ranks: prince, marquis, count, viscount, and baron.

In the transition between the Edo period and the Meiji era, the Ee ja nai ka movement, a spontaneous outbreak of ecstatic behavior, took place.

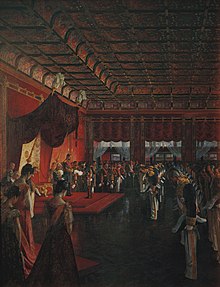

[8] The elite class of the Meiji era adapted many aspects of Victorian taste, as seen in the construction of Western-style pavilions and reception rooms called yōkan or yōma in their homes.

Integrating Western cultural forms with an assumed, untouched native Japanese spirit was characteristic of Meiji society, especially at the top levels, and represented Japan's search for a place within a new world power system in which European colonial empires dominated.

It inaugurated a new Western-based education system for all young people, sent thousands of students to the United States and Europe, and hired more than 3,000 Westerners to teach modern science, mathematics, technology, and foreign languages in Japan (O-yatoi gaikokujin).

The process of modernization was closely monitored and heavily subsidized by the Meiji government, enhancing the power of the great zaibatsu firms such as Mitsui and Mitsubishi.

Other economic reforms passed by the government included the creation of a unified modern currency based on the yen, banking, commercial and tax laws, stock exchanges, and a communications network.

Greatly concerned about national security, the leaders made significant efforts at military modernization, which included establishing a small standing army, a large reserve system, and compulsory militia service for all men.

In 1854, after US Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry forced the signing of the Treaty of Kanagawa, Japanese elites took the position that they needed to modernize the state's military capacities, or risk further coercion from Western powers.

Two days later, Saigō's rebels, while attempting to block a mountain pass, encountered advanced elements of the national army en route to reinforce Kumamoto castle.

The rebellion ended on September 24, 1877, following the final engagement with Imperial forces which resulted in the deaths of the remaining forty samurai including Saigō, who, having suffered a fatal bullet wound in the abdomen, was honorably beheaded by his retainer.

When the United States Navy ended Japan's Sakoku policy, and thus its isolation, the latter found itself defenseless against military pressures and economic exploitation by the Western powers.

Following World War I, a weakened Europe left a greater share in international markets to the United States and Japan, which emerged greatly strengthened.

Japanese competition made great inroads into hitherto-European-dominated markets in Asia, not only in China, but even in European colonies such as India and Indonesia, reflecting the development of the Meiji era.

[46] Other notable lacquer artists of the 19th century include Nakayama Komin and Shirayama Shosai, both of whom, in contrast with Zeshin, maintained a classical style that owed a lot to Japanese and Chinese landscape art.

[49] Suzuki Chokichi, a leading producer of cast bronze for international exhibition, became director of the Kiritsu Kosho Kaisha from 1874 to the company's dissolution in 1891.

[49] The works of Chokichi and his contemporaries took inspiration from late Edo period carvings and prints, combining and sometimes exaggerating traditional design elements in new ways to appeal to the export market.

[51] Some of these metalworkers were appointed Artists to the Imperial Household, including Kano Natsuo, Unno Shomin, Namekawa Sadakatsu, and Jomi Eisuke II.

[61] In the Meiji period, Japanese clothes began to be westernized and the number of people who wore kimono decreased, so the craftsmen who made netsuke and kiseru with ivory and wood lost their demand.

[62] The 1902 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica wrote, "In no branch of applied art does the decorative genius of Japan show more attractive results than that of textile fabrics, and in none has there been more conspicuous progress during recent years.

In the military field, the Japanese conducting school was formed, the founders of which were English, French and German cultural figures such as John William Fenton, Charles Leroux, and Franz Eckert.