Melville Monument

Plans to construct a memorial to him began soon after his death in 1811 and were largely driven by Royal Navy officers, especially Sir William Johnstone Hope.

During the 21st century, the monument became the subject of increasing controversy due to Dundas' legacy, especially debates over the extent of his role in legislating delays to the abolition of British involvement in the Atlantic slave trade.

The column is topped by a 4.2 m (14 ft) tall statue of Dundas designed by Francis Leggatt Chantrey and carved by Robert Forrest.

[8] Dundas gained influence under Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger and soon became Home Secretary: in this role, he suppressed popular unrest during the French Revolution.

In March 1821, shortly before construction began, a correspondent in The Scotsman, a Whig newspaper, argued the existence of this statue made another memorial to the same figure in the same city irrelevant.

[16] This may have motivated Vice Admiral Sir William Johnstone Hope to initiate a movement for such a monument within the Royal Navy.

[18][19] In its initial stages, the project was both led by naval officers and supported exclusively by subscriptions from sailors; although civic and legal figures were represented on the committee.

[15][21] The form and location of the monument were not initially settled and Hope first successfully applied to the town council for a site at the north east edge of Calton Hill.

On 28 April 1821, the anniversary of Dundas' birth, Admirals Otway and Milne laid the foundation stone and a time capsule was sealed into the structure; George Baird, Principal of the University of Edinburgh said prayers as part of the ceremony.

[28][31] Debt and delay grew, especially after an assessment by Robert Stevenson recommend strengthening the foundations and constructing the shaft from solid blocks rather than rubble infill as Burn had proposed.

[33] Stevenson's assessment was offered free of charge and had been spurred by the square's residents, many of whom were fearful of the stability of such a large monument.

[34][35] Despite these problems, the committee persevered and, in 1822, agreed to include a statue, designed by Francis Leggatt Chantrey and carved by Robert Forrest.

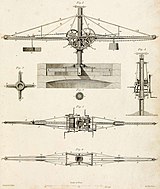

In summer 1827, the sculpture was erected at the top of the monument, having been brought from Forrest's workshop in twelve carts and pulled up, block-by-block, via pulleys on an external scaffold.

[38][39] Before and after the monument's completion, the committee's strong connections with the Royal Navy had made it reluctant to canvass public support to pay off the project's massive debts.

[45] In that decade, the town council recorded the complaints of citizens who objected to the city's maintenance of a memorial to an "unpopular" figure whose policies were "unwise and offensive".

[20] Despite these criticisms and controversies over Dundas' legacy, Connie Byrom assesses most contemporary reactions to the column's appearance to be positive.

Desmarest argues the monument is "imperial in character and context": part of a general movement around the turn of the nineteenth century to honour heroes of Britain's empire.

[53] In 2017, the city council, responding to a petition from environmental campaigner, Adam Ramsay, convened a committee to draft the wording of a new plaque to reflect controversial aspects of Dundas' legacy, including his role in the delay in the abolition of the slave trade.

[55][56] In early June 2020, Palmer, responding to the international outcry over the murder of George Floyd, reiterated calls for a new plaque.

These bore the intended wording of the permanent plaque, which had been drafted by a sub-committee including representatives of the council and Edinburgh World Heritage along with Palmer.

[59] In March 2021, the council approved the installation of a permanent plaque "dedicated to the memory of the more than half a million Africans whose enslavement was a consequence of Henry Dundas's actions".

The plaque also states Dundas "defended and expanded the British empire, imposing colonial rule on indigenous peoples" and "curbed democratic dissent in Scotland".

By the time of the monument's construction, however, the square had declined as a residential area and was, as it remains, largely occupied by commercial properties.

Gillespies' plan created a south west to north east axis across the square, which includes a central oval-shaped open space surrounding the monument.

[72] As the Melville Monument rose, some proposed a similar column, based on that of Antoninus Pius and dedicated to Pitt the Younger for Charlotte Square.

The square pedestal at the base of the monument more closely imitates that of its Roman model, especially in the corner eagles with oak leaf swags stretching between them.

[34][51] The statue, designed by Francis Leggatt Chantrey and carved by Robert Forrest, is constructed from Nethanfoot and Threepwood sandstone and stands at approximately 4.2 m (14 ft) tall.

[1] The statue depicts its subject clad in the robes of a peer and facing west along George Street with his left hand on his chest and his right foot slightly overstepping the pedestal.

[20][69] In the children's television series Hububb, which aired on CBBC from 1997 to 2001, the main character, played by mime artist Les Bubb, lives in the Melville Monument.

[79] The programme's producer, Parisa Urquhart, defended her work, pointing to positive comments from the Wilberforce Diaries Project and from Professor James Smith, Chair of Africa and Development Studies at the University of Edinburgh.