Meme

[4] A meme acts as a unit for carrying cultural ideas, symbols, or practices, that can be transmitted from one mind to another through writing, speech, gestures, rituals, or other imitable phenomena with a mimicked theme.

[11] Some commentators in the social sciences question the idea that one can meaningfully categorize culture in terms of discrete units, and are especially critical of the biological nature of the theory's underpinnings.

[15] Although Dawkins said his original intentions had been simpler, he approved Humphrey's opinion and he endorsed Susan Blackmore's 1999 project to give a scientific theory of memes, complete with predictions and empirical support.

[16] The term meme is a shortening (modeled on gene) of mimeme, which comes from Ancient Greek mīmēma (μίμημα; pronounced [míːmɛːma]), meaning 'imitated thing', itself from mimeisthai (μιμεῖσθαι, 'to imitate'), from mimos (μῖμος, 'mime').

"[24] G. K. Chesterton (1922) observed the similarity between intellectual systems and living organisms, noting that a certain degree of complexity, rather than being a hindrance, is a necessity for continued survival.

[23] Kenneth Pike had, in 1954, coined the related terms emic and etic, generalizing the linguistic units of phoneme, morpheme, grapheme, lexeme, and tagmeme (as set out by Leonard Bloomfield), distinguishing insider and outside views of communicative behavior.

The lack of a consistent, rigorous, and precise understanding of what typically makes up one unit of cultural transmission remains a problem in debates about memetics.

[35] Regardless of Internet Memetic's divergence in theoretical interests, it plays a significant role in theorizing and empirically investigating the connection between cultural ideologies, behaviors, and their mediation processes.

While the identification of memes as "units" conveys their nature to replicate as discrete, indivisible entities, it does not imply that thoughts somehow become quantized or that "atomic" ideas exist that cannot be dissected into smaller pieces.

Susan Blackmore writes that melodies from Beethoven's symphonies are commonly used to illustrate the difficulty involved in delimiting memes as discrete units.

It has been argued however that the traces of memetic processing can be quantified utilizing neuroimaging techniques which measure changes in the "connectivity profiles between brain regions".

Each tool-design thus acts somewhat similarly to a biological gene in that some populations have it and others do not, and the meme's function directly affects the presence of the design in future generations.

Similar memes are thereby included in the majority of religious memeplexes, and harden over time; they become an "inviolable canon" or set of dogmas, eventually finding their way into secular law.

[52] Thus, memetics attempts to apply conventional scientific methods (such as those used in population genetics and epidemiology) to explain existing patterns and transmission of cultural ideas.

[55] In his book Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Daniel C. Dennett points to the existence of self-regulating correction mechanisms (vaguely resembling those of gene transcription) enabled by the redundancy and other properties of most meme expression languages which stabilize information transfer.

[56] Dennett notes that spiritual narratives, including music and dance forms, can survive in full detail across any number of generations even in cultures with oral tradition only.

Kim Sterelny and Paul Griffiths noted the cumulative evolution of genes depends on biological selection-pressures neither too great nor too small in relation to mutation-rates, while pointing out there is no reason to think that the same balance will exist in the selection pressures on memes.

[61][62] A third approach, described by Joseph Poulshock, as "radical memetics" seeks to place memes at the centre of a materialistic theory of mind and of personal identity.

[63] Prominent researchers in evolutionary psychology and anthropology, including Scott Atran, Dan Sperber, Pascal Boyer, John Tooby and others, argue the possibility of incompatibility between modularity of mind and memetics.

People with autism showed a significant tendency to closely paraphrase and repeat content from the original statement (for example: "Don't cut flowers before they bloom").

Specifically, Stanovich argues that the use of memes as a descriptor for cultural units is beneficial because it serves to emphasize transmission and acquisition properties that parallel the study of epidemiology.

His theory of "cultural software" maintained that memes form narratives, social networks, metaphoric and metonymic models, and a variety of different mental structures.

For instance, tribal religion has been seen as a mechanism for solidifying group identity, valuable for a pack-hunting species whose individuals rely on cooperation to catch large and fast prey.

For example, religions that preach of the value of faith over evidence from everyday experience or reason inoculate societies against many of the most basic tools people commonly use to evaluate their ideas.

Lynch asserts that belief in the Crucifixion of Jesus in Christianity amplifies each of its other replication advantages through the indebtedness believers have to their Savior for sacrifice on the cross.

The image of the crucifixion recurs in religious sacraments, and the proliferation of symbols of the cross in homes and churches potently reinforces the wide array of Christian memes.

Robertson (2007)[67] reasoned that if evolution is accelerated in conditions of propagative difficulty,[68][page needed] then we would expect to encounter variations of religious memes, established in general populations, addressed to scientific communities.

Advantages of a memetic approach as compared to more traditional "modernization" and "supply side" theses in understanding the evolution and propagation of religion were explored.

[69] Taking reference to Dawkins, Salingaros emphasizes that they can be transmitted due to their own communicative properties, that "the simpler they are, the faster they can proliferate", and that the most successful memes "come with a great psychological appeal".

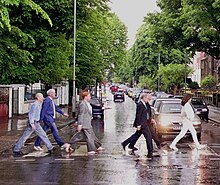

[74] In 2013, Dawkins characterized an Internet meme as one deliberately altered by human creativity, distinguished from his original idea involving mutation "by random change and a form of Darwinian selection".