Menachem HaMeiri

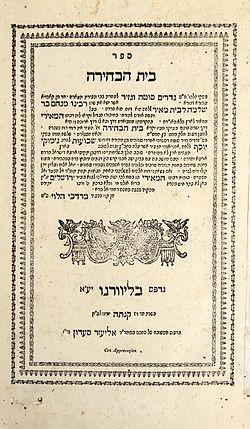

This work is less a commentary and more of a digest of all of the comments in the Talmud, arranged in a manner similar to the Talmud—presenting first the mishnah and then laying out the discussions that are raised concerning it.

[6] Haym Soloveitchik describes it as follows:[7] Unlike most rishonim, he frequently quotes the Jerusalem Talmud, including textual variants which are no longer extant in other sources.

[8] Snippets of Beit HaBechirah on one Tractate, Bava Kamma, were published long before the publication of the Parma manuscripts, included in the early collective work Shitah Mikubetzet.

[3] The common assumption has been that the large majority of the Meiri's works were not available to generations of halachists before 1920; as reflected in early 20th century authors such as the Chafetz Chaim, the Chazon Ish, and Joseph B. Soloveitchik who write under the assumption that Beit HaBechira was newly discovered in their time,[8] and further evidenced by the lack of mention of the Meiri and his opinions in the vast literature of halacha writings before the early 20th century.

Some modern poskim refuse to take its arguments into consideration, on the grounds that a work so long unknown has ceased to be part of the process of halachic development.

[8] Professor Haym Soloveitchik, though, suggested that the work was ignored due to its having the character of a secondary source – a genre which, he argues, was not appreciated among Torah learners until the late 20th century.

[9][7] Menachem HaMeiri is also noted for having penned a famous work used to this very day by Jewish scribes, namely, Kiryat Sefer, a two-volume compendium outlining the rules governing the orthography that are to be adhered to when writing Torah scrolls.