Merced Assembly Center

The Merced Assembly Center, located in Merced, California, was one of sixteen temporary assembly centers hastily constructed in the wake of Executive Order 9066 to incarcerate those of Japanese ancestry beginning in the spring of 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor and prior to the construction of more permanent concentration camps to house those forcibly removed from the West Coast.

[3] After the attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Asian prejudice rapidly began spreading through the West Coast, mainly affecting the state of California.

[4] After the Alien Registration Act of 1940, the FBI made a list of potentially dangerous immigrants who were German, Italian, or Japanese.

[6] As a result of Executive Order 9066, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were forced to relocate to temporary "assembly centers" primarily located within the Central Valley.

The evacuees were not allowed to take a lot of their belongings with them, with only one duffel bag and two suitcases leaving the rest to be sold or stored.

Due to everything happening so fast, everything was being sold at unfair prices and people were taking advantage of any items that the Japanese Americans were leaving behind.

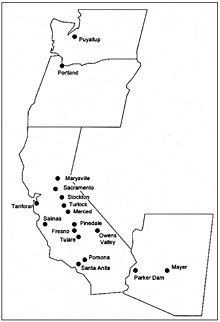

The locations of these centers in California were: Fresno, Owens Valley, Marysville, Merced, Pinedale, Pomona, Sacramento, Salinas, Santa Anita, Stockton, Tanforan, Tulare, and Turlock.

The mess halls of the centers became potential breeding sites for epidemic outbreaks, compounding the health dangers of the unsanitary living quarters.

[10] The Western Defense Command put out 108 Civilian Exclusion Orders to forcibly relocate people of Japanese ancestry who lived on the West Coast.

The first order went out on March 24, 1942 for 55 families closest to the attack on Pearl Harbor, who would eventually be sent to Manzanar and Minidoka internment camps.

[14] This forced relocation process was documented by Dorothea Lange, an American photographer hired by the government to show how well the Japanese internees were being treated in the camps.

The existence of the images to the public today is mainly due to their transmission into the National Archives and their presence in the traveling exhibition, Executive Order 9066, by Richard Conrad, Lange’s assistant, and his wife.

In order to justify the perception that the government wanted to show, Lange was told not to make sure barbed wire, watchtowers, and armed soldiers were not depicted in any of the images.

The police also screened all visitors and incoming luggage and parcels for contraband, though mail remained protected from surveillance and censorship.

[19] Medical facilities included doctor’s offices, hospital wards, a pharmacy, a dental clinic, and a dietician's unit.

Strong of Electrolux Corporation, he writes that “there has been a number of unnecessary deaths” due to lack of medical resources and attention.

Fujita’s letter further details the kind of conditions that Japanese Americans were forced to endure during this time period that may have contributed to the 10 deaths that occurred at the detention center.

[21] Since the government did not have the resources at the time to incarcerate 110,000 people adequately, most of the assembly centers were repurposed from existing race tracks or fairgrounds, including at Merced.

As Marion Michiko Bernardo, who was incarcerated at the Merced Assembly Center as a young girl, remembers, "The rooftops were at this angle and there was no ceiling in between the whole building.

Ruth Ihara, who was incarcerated at the Merced Assembly Center, described the conditions she encountered in a letter: "When we first saw our living quarters we were so sick we couldn't, eat, walk, or talk.

"[24] The barracks did not have kitchens and meals were served in a central mess hall, staffed by Japanese American cooks incarcerated at the detention center.

The food was of poor quality, unfamiliar and unappetizing to Japanese Americans, and the cooks struggled to prepare edible meals.

[25] Because the detention center operated from the late spring through the early fall in a region that routinely experiences triple-digit temperatures, those incarcerated at Merced had to cope with extreme heat.

[12] As Harry Fujita, who was incarcerated at Merced, wrote in a letter at the time, "In the prevailing hot weather our rooms are just like ovens.

High school subjects included English, Algebra, Geometry, Trigonometry, Gen.Science, Chemistry, American History, Government, Bookkeeping, and Business Training.

The detention center also held a ceremony for students who missed their high school graduation due to their forced relocation.

[35][36] To keep operating costs low, the WCCA employed the incarcerated in the everyday work of running the assembly centers.

[13] Beginning in June 1942, the WCCA also provided the incarcerated with monthly allowances to purchase basic necessities such as food, hygiene items, and clothing.

[43] Initially, authorities planned to send groups of 500 from Merced to Amache daily, but they soon realized that they would need more time because the camp was not ready to hold that many people.

[48] The memorial consists of the names of those incarcerated at the assembly center, along with a statue of families waiting with their luggage in front of the wall and a reflection pool behind it.