Merchant

During the European medieval period, a rapid expansion in trade and commerce led to the rise of a wealthy and powerful merchant class.

In modern times, the term merchant has occasionally been used to refer to a businessperson or someone undertaking activities (commercial or industrial) for the purpose of generating profit, cash flow, sales, and revenue using a combination of human, financial, intellectual and physical capital with a view to fueling economic development and growth.

Open-air, public markets, where merchants and traders congregated, functioned in ancient Babylonia and Assyria, China, Egypt, Greece, India, Persia, Phoenicia and Rome.

Surrounding the market, skilled artisans, such as metal-workers and leather workers, occupied premises in alley ways that led to the open market-place.

Phoenician merchant traders imported and exported wood, textiles, glass and produce such as wine, oil, dried fruit and nuts.

Their trading necessitated a network of colonies along the Mediterranean coast, stretching from modern-day Crete through to Tangiers (in present-day Morocco) and northward to Sardinia.

Mosaic patterns in the floor of his atrium were decorated with images of amphorae bearing his personal brand and inscribed with quality claims.

Scaurus' fish sauce had a reputation for very high quality across the Mediterranean; its fame travelled as far away as modern southern France.

Archaeologists have recovered Roman objects dating from the period 27 BCE to 37 CE from excavation sites as far afield as the Kushan and Indus ports.

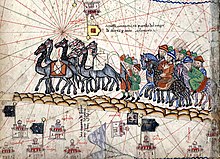

[29] Medieval England and Europe witnessed a rapid expansion in trade and the rise of a wealthy and powerful merchant class.

In the early 12th century, a confederation of merchant guilds, formed out the German cities of Lübeck and Hamburg, known as "The Hanseatic League" came to dominate trade around the Baltic Sea.

These arrangements first appeared on the route from Italy to the Levant, but by the end of the thirteenth century merchant colonies could be found from Paris, London, Bruges, Seville, Barcelona and Montpellier.

Direct sellers, who brought produce from the surrounding countryside, sold their wares through the central market place and priced their goods at considerably lower rates than cheesemongers.

The local markets, where people purchased their daily needs were known as tianguis while pochteca referred to long-distance, professional merchants traders who obtained rare goods and luxury items desired by the nobility.

[38] In much of Renaissance Europe and even after, merchant trade remained seen as a lowly profession and it was often subject to legal discrimination or restrictions, although in a few areas its status began to improve.

[39][40][41][42][43] The modern era is generally understood to refer to period that started with the rise of consumer culture in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe.

[44][need quotation to verify] As standards of living improved in the 17th century, consumers from a broad range of social backgrounds began to purchase goods that were in excess of basic necessities.

An emergent middle class or bourgeoisie stimulated demand for luxury goods, and the act of shopping came to be seen as a pleasurable pastime or form of entertainment.

[46] As Britain continued colonial expansion, large commercial organisations came to provide a market for more sophisticated information about trading conditions in foreign lands.

Daniel Defoe (c. 1660–1731), a London merchant, published information on trade and economic resources of England, Scotland and India.

Armenians had established prominent trade-relations with all big export players such as India, China, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, England, Venice, the Levant, etc.

[50] Eighteenth-century merchants who traded in foreign markets developed a network of relationships which crossed national boundaries, religious affiliations, family ties, and gender.

The historian, Vannneste, has argued that a new "cosmopolitan merchant mentality" based on trust, reciprocity and a culture of communal support developed and helped to unify the early modern world.

[53] McKendrick, Brewer and Plumb found extensive evidence of eighteenth-century English entrepreneurs and merchants using "modern" marketing techniques, including product differentiation, sales promotion and loss-leader pricing.

He also inferred that selling at lower prices would lead to higher demand and recognised the value of achieving scale economies in production.

[57] Similarly, one of Wedgewood's contemporaries, Matthew Boulton, pioneered early mass-production techniques and product differentiation at his Soho Manufactory in the 1760s.

He also practiced planned obsolescence and understood the importance of "celebrity marketing" – that is supplying the nobility, often at prices below cost – and of obtaining royal patronage, for the sake of the publicity and kudos generated.

Other merchants profited from natural resources (the Hudson's Bay Company theoretically controlled much of North America, names like Rockefeller and Nobel dominated trade in oil in the US and in the Russian Empire), while still others made fortunes from exploiting new inventions – selling space on and commodities carried by railways and steamships.

[citation needed] In 2022, Dutch photographer Loes Heerink spend hours on bridges in Hanoi to take pictures of Vietnamese street Merchants.

[67] During the 12th century, powerful guilds which controlled the way that trade was conducted were established and were often incorporated into the charters granted to market towns.