Merseburg charms

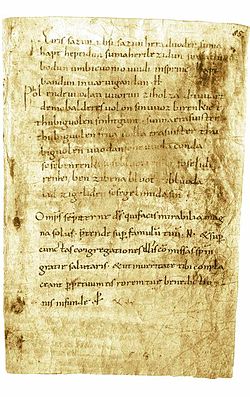

They were discovered in 1841 by Georg Waitz,[1] who found them in a theological manuscript from Fulda, written in the 9th century,[2] although there remains some speculation about the date of the charms themselves.

[3] The charms were recorded in the 10th century by a cleric, possibly in the abbey of Fulda, on a blank page of a liturgical book, which later passed to the library at Merseburg.

[citation needed] Each charm is divided into two parts: a preamble telling the story of a mythological event; and the actual spell in the form of a magic analogy (just as it was before... so shall it also be now...).

[5] The first spell is a "Lösesegen" (blessing of release), describing how a number of "Idisen" freed from their shackles warriors caught during battle.

Depictions found on Migration Period Germanic bracteates are often viewed as Wodan (Odin) healing a horse.

[18] In this Christianized example, it is the singing of the mass, rather than the chanting of the charm, that effects the release of a comrade (in this case a brother).

Bugge makes this reference in his edition of the Eddaic poem Grógaldr (1867), in an attempt to justify his emending the phrase "Leifnir's fire (?)"

[20] But this is an aggressive emendation of the original text, and its validity as well as any suggestion to its ties to the Merseburg charm is subject to skepticism.

Similar charms have been noted in Gaelic, Lettish and Finnish[23] suggesting that the formula is of ancient Indo-European origin.

[18] There are several manuscript recensions of this spell, and Jacob Grimm scrutinizes in particular the so-called "Contra vermes" variant, in Old Saxon[25] from the Cod.

[25] Grimm insists that this charm, like the De hoc quod Spurihalz dicunt charm (MHG: spurhalz; German: lahm "lame") that immediately precedes it in the manuscript, is "about lame horses again" And the "transitions from marrow to bone (or sinews), to flesh and hide, resemble phrases in the sprain-spells", i.e. the Merseburg horse-charm types.

Jacob Grimm in his Deutsche Mythologie, chapter 38, listed examples of what he saw as survivals of the Merseburg charm in popular traditions of his time: from Norway a prayer to Jesus for a horse's leg injury, and two spells from Sweden, one invoking Odin (for a horse suffering from a fit or equine distemper[28][b]) and another invoking Frygg for a sheep's ailment.

[18] He also quoted one Dutch charm for fixing a horse's foot, and a Scottish one for the treatment of human sprains that was still practiced in his time in the 19th century (See #Scotland below).

Bishop Anton Christian Bang compiled a volume culled from Norwegian black books of charms and other sources, and classified the horse-mending spells under the opening chapter "Odin og Folebenet", strongly suggesting a relationship with the second Merseburg incantation.

[34] Bang here gives a group of 34 spells, mostly recorded in the 18th–19th century though two are assigned to the 17th (c. 1668 and 1670),[29] and 31 of the charms[35] are for treating horses with an injured leg.

[f] The idea that the charms have been Christianized and that the presence of Baldur has been substituted by "The Lord" or Jesus is expressed by Bang in another treatise,[42] crediting communications with Bugge and the work of Grimm in the matter.

Jacob Grimm had already pointed out the Christ-Balder identification in interpreting the Merseburg charm; Grimm seized on the idea that in the Norse language, "White Christ (hvíta Kristr)" was a common epithet, just as Balder was known as the "white Æsir-god"[43] Another strikingly similar "horse cure" incantation is a 20th-century sample that hails the name of the ancient 11th-century Norwegian king Olaf II of Norway.

The specimen was collected in Møre, Norway, where it was presented as for use in healing a bone fracture: This example too has been commented as corresponding to the second Merseburg Charm, with Othin being replaced by Saint Olav.

The following 17th-century spell was noted as a parallel to the Merseburg horse charm by both of them:[46][47] Another example (from Kungelf's Dombok, 1629) was originally printed by Arcadius:[49][50] Vår herre red ad hallen ned.

A spell beginning "S(anc)te Pär och wår Herre de wandrade på en wäg (from Sunnerbo hundred, Småland 1746) was given originally by Johan Nordlander.

A Danish parallel noted by A. Kuhn[53] is the following: Imod Forvridning (Jylland) Jesus op ad Bierget red; der vred han sin Fod af Led.

[18] This healing spell for humans was practiced in Shetland[55][56] (which has strong Scandinavian ties and where the Norn language used to be spoken).

The practice involved tying a "wresting thread" of black wool with nine knots around the sprained leg of a person, and in an inaudible voice pronouncing the following: The Lord rade and the foal slade; he lighted and he righted, set joint to joint, bone to bone, and sinew to sinew Heal in the Holy Ghost's name!

[18][55][56] Alexander Macbain (who also supplies a presumably reconstructed Gaelic "Chaidh Criosd a mach/Air maduinn mhoich" to the first couplet of "The Lord rade" charm above[57]) also records a version of a horse spell which was chanted while "at the same time tying a worsted thread on the injured limb".

[58] Chaidh Criosda mach Sa' mhaduinn mhoich 'S fhuair e casan nan each, Air am bristeadh mu seach.

Macbain goes on to quote another Gaelic horse spell, one beginning "Chaidh Brìde mach.." from Cuairtear nan Gleann (July 1842) that invokes St. Bride as a "he" rather than "she", plus additional examples suffering from corrupted text.