Mesa Verde National Park

By 1285, following a period of social and environmental instability driven by a series of severe and prolonged droughts, they migrated south to locations in Arizona and New Mexico, including the Rio Chama, the Albuquerque Basin, the Pajarito Plateau, and the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

[7] The early Archaic people living near Mesa Verde utilized the atlatl and harvested a wider variety of plants and animals than the Paleo-Indians had while retaining their primarily nomadic lifestyle.

Major warming and drying from 5000 to 2500 might have led middle Archaic people to seek the cooler climate of Mesa Verde, whose higher elevation brought increased snowpack that, when coupled with spring rains, provided relatively plentiful amounts of water.

[8] With the introduction of corn to the Mesa Verde region c. 1000 BC and the trend away from nomadism toward permanent pithouse settlements, the Archaic Puebloan transitioned into what archaeologists call the Basketmaker culture.

[9][a] In addition to the fine basketry for which they were named, Basketmaker II people fashioned a variety of household items from plant and animal materials, including sandals, robes, pouches, mats, and blankets.

Their skeletal remains reveal signs of hard labor and extensive travel, including degenerative joint disease, healed fractures, and moderate anemia associated with iron deficiency.

Basketmakers endeavored to store enough food for their family for one year, but also retained residential mobility so they could quickly relocate their dwellings in the event of resource depletion or consistently inadequate crop yields.

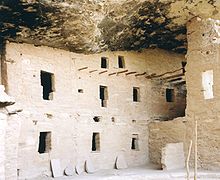

These Mesa Verde-style kivas included a feature from earlier times called a sipapu, which is a hole dug in the north of the chamber and symbolizes the Ancestral Puebloan's place of emergence from the underworld.

[27] The expansion of Chacoan influence in the Mesa Verde area left its most visible mark in the form of Chaco-style masonry great houses that became the focal point of many Puebloan villages after 1075.

Population increases also led to expanded tree felling that reduced habitat for many wild plant and animal species that the Puebloan had relied on, further deepening their dependency on domesticated crops that were susceptible to drought-related failure.

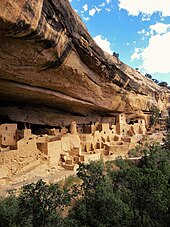

[36] Ancestral Pueblo villages thrived during the mid-Pueblo III Era, when architects constructed massive, multi-story buildings, and artisans adorned pottery with increasingly elaborate designs.

[52] The archaeological record indicates that, rather than being isolated to the Mesa Verde region, violent conflict was widespread in North America during the late 13th and early 14th centuries, and was likely exacerbated by global climate changes that negatively affected food supplies throughout the continent.

[55][56] The Ancestral Puebloans had a long history of migration in the face of environmental instability, but the depopulation of Mesa Verde at the end of the 13th century was different in that the region was almost completely emptied, and no descendants returned to build permanent settlements.

[57] While drought, resource depletion, and overpopulation all contributed to instability during the last two centuries of Ancestral Puebloan occupation, their overdependence on maize crops is considered the "fatal flaw" of their subsistence strategy.

[62] Although the rate of settlement is unclear, increases in sparsely populated areas, such as Rio Chama, Pajarito Plateau, and Santa Fe, correspond directly with the period of migration from Mesa Verde.

Archaeologists believe the Puebloans who settled in the areas near the Rio Grande, where Mesa Verde black-on-white pottery became widespread during the 14th century, were likely related to the households they joined and not unwelcome intruders.

[73] While much of the construction in these sites is consistent with common Pueblo architectural forms, including kivas, towers, and pit-houses, the space constrictions of these alcoves necessitated what seems to have been a far denser concentration of their populations.

Several great houses in the region were aligned to the cardinal directions, which positioned windows, doors, and walls along the path of the sun, whose rays would indicate the passing of seasons.

[76] It is aligned to the major lunar standstill, which occurs once every 18.6 years, and the sunset during the winter solstice, which can be viewed setting over the temple from a platform at the south end of Cliff Palace, across Fewkes Canyon.

Depending on the season, they collected piñon nuts and juniper berries, weedy goosefoot, pigweed, purslane, tomatillo, tansy mustard, globe mallow, sunflower seeds, and yucca, as well as various species of grass and cacti.

[91][i] Evidence that pottery of both types moved between several locations around the region suggests interaction between groups of ancient potters, or they might have shared a common source of raw materials.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the Plant Hardiness zone at Mesa Verde National Park Headquarters at 6952 ft (2119 m) elevation is 6b with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of −0.1 °F (−17.8 °C).

[85] A shift from medium and large game animals, such as deer, bighorn sheep, and antelope, to smaller ones like rabbits and turkey during the mid-10th to mid-13th centuries might indicate that Pueblonian subsistence hunting had dramatically altered faunal populations on the mesa.

[107] Analysis of pack rat midden indicates that, with the exception of invasive species such as tumbleweed and clover, the flora and fauna in the area have remained relatively consistent for the past 4,000 years.

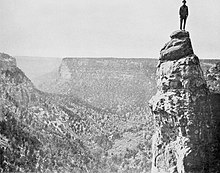

This sandstone, which formed in the marine environment of shallow water when the Cretaceous sea was receding, is "massive, fine-grained, cross-bedded, and very resistant", in its layers reflecting waves and currents that were present during the time of its formation.

[111] Mexican-Spanish missionaries and explorers Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, seeking a route from Santa Fe to California, faithfully recorded their travels in 1776.

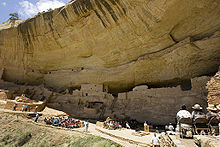

[120][121] Nordenskiöld was a trained mineralogist who introduced scientific methods to artifact collection, recorded locations, photographed extensively, diagrammed sites, and correlated what he observed with existing archaeological literature as well as the home-grown expertise of the Wetherills.

A fellow activist for protection of Mesa Verde and prehistoric archaeological sites included Lucy Peabody, who, located in Washington, D.C., met with members of Congress to further the cause.

In order to secure this valuable archaeological material, walls were broken down ... often simply to let light into the darker rooms; floors were invariably opened and buried kivas mutilated.

These three small and separate sections of the National Park are located on the steep north and east boundaries and serve as buffers to further protect the significant Native American sites.