Mesoamerican calendars

The calendrical systems devised and used by the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica, primarily a 260-day year, were used in religious observances and social rituals, such as divination.

[5] Apparently the earliest Mesoamerican calendar to be developed was known by a variety of local terms, and its named components and the glyphs used to depict them were culture-specific.

However, it is clear that type of calendar functioned in essentially the same way across cultures, and across the chronological periods when it was maintained.

[6] Because it was an approximation, over time the seasons and the true tropical year gradually "wandered" with respect to this calendar, owing to the accumulation of the differences in length.

There is little hard evidence to suggest that the ancient Mesoamericans used any intercalary days to bring their calendar back into alignment.

The completion and observance of this Calendar Round sequence was of ritual significance to a number of Mesoamerican cultures.

A third major calendar form known as the Long Count is found in the inscriptions of several Mesoamerican cultures, most famously those of the Maya civilization who developed it to its fullest extent during the Classic period (ca.

The Long Count provided the ability to uniquely identify days over a much longer period of time, by combining a sequence of day-counts or cycles of increasing length, calculated or set from a particular date in the mythical past.

Earliest written evidence for the 260 calendar include the San Andres glyphs (Olmec, 650 BCE, giving the possible date 3 Ajaw[11]) and the San Jose Mogote danzante (Zapotec, 600 - 500 BCE, giving the possible date 1 Earthquake[12]), in both cases assumed to be used as names.

However, the earliest evidence of the use of the 260-day cycle comes from astronomical alignments in the Olmec region and western Maya Lowlands, dating to about 1100 BCE.

The Mesoamerican calendar probably originated with the Olmecs, and a settlement existed at Izapa, in southeast Chiapas, Mexico, before 1200 BCE.

While waiting for this to happen, all fire was extinguished, utensils were destroyed to symbolize new beginnings, people fasted and rituals were carried out.

When dawn broke on the first day of the new cycle, torches were lit in the temples and brought out to light new fires everywhere, and ceremonies of thanksgiving were performed.

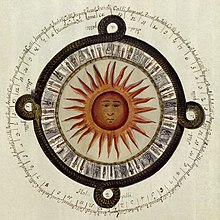

[19] The term calendar wheel generally refers to Colonial-period images that display cycles of time in a circular format.

[20] The earliest known Colonial-period calendar wheel is actually depicted in a square format, on pages 21 and 22 of the Codex Borbonicus, an Aztec screenfold that divides the 52-year cycle into two parts.

Some paired festivals share the same glyph, but they are represented in different sizes, the first being the “small feast” and the second the “great feast.” In the center, a 7 Rabbit date (1538) appears with text and images that refer to Tetzcocan town officers.

[citation needed] The use of the long count is best attested among the classic Maya, it is not known to have been used by the central Mexican cultures.

The Classic Maya, used the Long Count to record dates within periods longer than the 52 year calendar round.

These calendars differed from the Maya version mainly in that they didn't use the long count to fix dates into a larger chronological frame than the 52-year cycle.

This is the second oldest Long Count date yet discovered. The numerals 7.16.6.16.18 translate to September 1, 32 BCE (Gregorian). The glyphs surrounding the date are what is thought to be one of the few surviving examples of Epi-Olmec script .