Messe des pauvres

It was a spoof of the flamboyant Péladan, whose Rose + Croix creed ("the transformation of society through art") and habit of "excommunicating" his critics in bombastic letters to newspapers Satie gleefully adopted.

[6] Satie authorities Ornella Volta and Robert Orledge believe he conceived the mass to occupy his mind following his recent breakup with the painter Suzanne Valadon, which had left him emotionally devastated.

The texts Satie chose make no reference to the poor at large, giving further weight to speculations that, impoverished as he was, he essentially wrote the mass for his own solace.

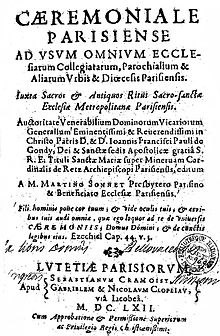

Portions of the Messe des pauvres appeared in two of them: an extract from the Commune qui mundi nefas in a pamphlet of the same name (January 1895), and the complete Dixit Domine - calligraphed in faux Gregorian notation by Satie - in the brochure Intende votis supplicum (March 1895).

That same month he exchanged his robes and religious affectations for the seven identical sets of corduroy suits that would come to define his "Velvet Gentleman" phase,[14] and for the better part of two years he wrote nothing.

In his next important work, the Pièces froides for piano (1897), Satie revisited the pre-Rose + Croix style of his Gnossiennes and turned his back on the mystical-religious influences he would later dismiss as "musique à genoux" ("music on its knees").

In its existing state - two choral movements followed by a series of organ solos - the Messe des pauvres does not conform to any liturgical tradition; but this is partly a result of circumstance.

Satie's probable model was the organ mass,[22] in which instrumental pieces (versets) were composed to replace sections of the Ordinarium or Vespers (evening service) that were otherwise chanted or sung.

[25][26] Pope Pius X would ban the alternatim practice altogether in 1903,[27] but in the meantime the flexibility the French variety offered can only have appealed to Satie, who was never content with rigid musical forms of any kind.

[29] Sketches of two or three pieces from Satie's notebooks of the period may relate to the work, but whether he planned to expand it or to provide plainsong-like text settings for some of the organ solos must remain speculative.

[30][31] The mysterious stasis of the music, and Satie's unique reimagining of medieval modes with some of his most innovative harmonic writing,[32] give the mass a haunting, timeless quality that is very effective in performance.