Messerschmitt Me 262

The project had originated with a request by the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM, Ministry of Aviation) for a jet aircraft capable of one hour's endurance and a speed of at least 850 km/h (530 mph; 460 kn).

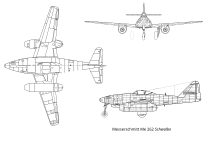

[23] Based on data from the AVA Göttingen and wind tunnel results, the inboard section's leading edge (between the nacelle and wing root) was later swept to the same angle as the outer panels, from the "V6" sixth prototype onward throughout volume production.

[26][27] The jet engine program was waylaid by a lack of funding, which was primarily due to a prevailing attitude amongst high-ranking officials that the conflict could be won easily with conventional aircraft.

Hitler's interference helped to extend the delay in bringing the Schwalbe into operation;[38][39] (other factors contributed too; in particular, there were engine vibration problems which needed attention).

According to Speer, Hitler felt its superior speed compared to other fighters of the era meant it could not be attacked, and so preferred it for high altitude straight flying.

[47] Its retracting conventional tail wheel gear (similar to other contemporary piston-powered propeller aircraft), a feature shared with the first four Me 262 V-series airframes, caused its jet exhaust to deflect off the runway, with the wing's turbulence negating the effects of the elevators, and the first takeoff attempt was cut short.

[48] On the second attempt, Wendel solved the problem by tapping the aircraft's brakes at takeoff speed, lifting the horizontal tail out of the wing's turbulence.

[53] However, the Jumo 004A engine proved unsuitable for full-scale production because of its considerable weight and its high utilization of strategic materials (nickel, cobalt, molybdenum), which were in short supply.

All high heat-resistant metal parts, including the combustion chamber, were changed to mild steel (SAE 1010) and were protected only against oxidation by aluminum coating.

[54] Frank Whittle concludes in his final assessment over the two engines: "it was in the quality of high temperature materials that the difference between German and British engines was most marked"[55] Operationally, carrying 2,000 litres (440 imperial gallons; 530 US gallons) of fuel in two 900-litre (200-imperial-gallon; 240-US-gallon) tanks, one each fore and aft of the cockpit; and a 200-litre (44-imperial-gallon; 53-US-gallon) ventral fuselage tank beneath,[Note 4] the Me 262 would have a total flight endurance of 60 to 90 minutes.

Sources state the Mosquito had a hatch fall out, during the evasive manoeuvres, though the aircraft returned to RAF Benson on 27 July 1944, and remained in service till it was lost in a landing in October 1950.

[citation needed] In the last days of the conflict, Me 262s from JG 7 and other units were committed in ground assault missions, in an attempt to support German troops fighting Red Army forces.

[77] Several two-seat trainer variants of the Me 262, the Me 262 B-1a, had been adapted through the Umrüst-Bausatz 1 factory refit package as night fighters, complete with on-board FuG 218 Neptun high-VHF band radar, using Hirschgeweih ("stag's antlers") antennae with a set of dipole elements shorter than the Lichtenstein SN-2 had used, as the B-1a/U1 version.

In a head-on attack, the combined closing speed of about 320 m/s (720 mph) was too high for accurate shooting with the relatively slow firing 30mm MK 108 cannon - at about 650 rounds/min this gave around 44 rounds per second from all four guns.

Some nicknamed this tactic the Luftwaffe's Wolf Pack[citation needed], as the fighters often made runs in groups of two or three, fired their rockets, then returned to base.

On 1 September 1944, USAAF General Carl Spaatz expressed the fear that if greater numbers of German jets appeared, they could inflict losses heavy enough to force cancellation of the Allied bombing offensive by daylight.

Another disadvantage that pioneering jet aircraft of the World War II era shared, was the high risk of compressor stall and if throttle movements were too rapid, the engine(s) could suffer a flameout.

The high speed of the Me 262 also presented problems when engaging enemy aircraft, the high-speed convergence allowing Me 262 pilots little time to line up their targets or acquire the appropriate amount of deflection.

[citation needed] Pilots soon learned that the Me 262 was quite maneuverable despite its high wing loading and lack of low-speed thrust, especially if attention was drawn to its effective maneuvering speeds.

The inclusion of full span automatic leading-edge slats,[Note 7] something of a "tradition" on Messerschmitt fighters dating back to the original Bf 109's outer wing slots of a similar type, helped increase the overall lift produced by the wing by as much as 35% in tight turns or at low speeds, greatly improving the aircraft's turn performance as well as its landing and takeoff characteristics.

[Note 8] As a result, Me 262 pilots were relatively safe from the Allied fighters, as long as they did not allow themselves to get drawn into low-speed turning contests and saved their maneuvering for higher speeds.

[citation needed] Allied pilots soon found that the only reliable way to destroy the jets, as with the even faster Me 163B Komet rocket fighters, was to attack them on the ground or during takeoff or landing.

Hubert Lange, a Me 262 pilot, said: "the Messerschmitt Me 262's most dangerous opponent was the British Hawker Tempest—extremely fast at low altitudes, highly manoeuvrable and heavily armed.

[110] Interest in high-speed flight, which led him to initiate work on swept wings starting in 1940, is evident from the advanced developments Messerschmitt had on his drawing board in 1944.

[113] After the war, the Royal Aircraft Establishment, at that time one of the leading institutions in high-speed research, re-tested the Me 262 to help with British attempts at exceeding Mach 1.

[citation needed] After Willy Messerschmitt's death in 1978, the former Me 262 pilot Hans Guido Mutke claimed to have exceeded Mach 1 on 9 April 1945 in a Me 262 in a "straight-down" 90° dive.

The Me 262 wing had only a slight sweep, incorporated for trim (center of gravity) reasons and likely would have suffered structural failure due to divergence at high transonic speeds.

[116][117] US tests conducted at the Royal Aircraft bas in Farnborough in October 1945 showed the ME 262 achieving 540 miles per hour (869 kph), with the engine at maxiumum RPM.

In January 2003, the American Me 262 Project, based in Everett, Washington, completed flight testing to allow the delivery of partially updated spec reproductions of several versions of the Me 262 including at least two B-1c two-seater variants, one A-1c single-seater and two "convertibles" that could be switched between the A-1c and B-1c configurations.

The "c" suffix refers to the new CJ610 powerplant and has been informally assigned with the approval of the Messerschmitt Foundation in Germany[135] (the Werknummer of the reproductions picked up where the last wartime produced Me 262 left off – a continuous airframe serial number run with a near 60-year production break).