Messiah (Handel)

In his libretto, Jennens's intention was not to dramatise the life and teachings of Jesus, but to acclaim the "Mystery of Godliness",[15] using a compilation of extracts from the Authorized (King James) Version of the Bible, and from the Psalms included in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

Part II covers Christ's passion and his death, his resurrection and ascension, the first spreading of the gospel through the world, and a definitive statement of God's glory summarised in the Hallelujah.

Part III begins with the promise of redemption, followed by a prediction of the day of judgment and the "general resurrection", ending with the final victory over sin and death and the acclamation of Christ.

[21] His religious and political views—he opposed the Act of Settlement of 1701 which secured the accession to the British throne for the House of Hanover—prevented him from receiving his degree from Balliol College, Oxford, or from pursuing any form of public career.

As a devout Anglican and believer in scriptural authority, Jennens intended to challenge advocates of Deism, who rejected the doctrine of divine intervention in human affairs.

[14] Shaw describes the text as "a meditation of our Lord as Messiah in Christian thought and belief", and despite his reservations on Jennens's character, concedes that the finished wordbook "amounts to little short of a work of genius".

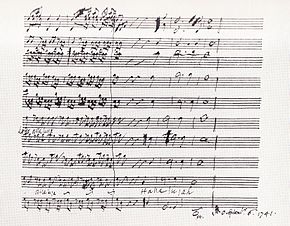

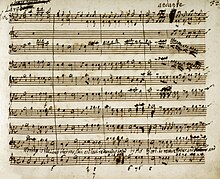

[28][29] In accordance with his practice when writing new works, Handel adapted existing compositions for use in Messiah, in this case drawing on two recently completed Italian duets and one written twenty years previously.

Avoglio and Cibber were again the chief soloists; they were joined by the tenor John Beard, a veteran of Handel's operas, the bass Thomas Rheinhold and two other sopranos, Kitty Clive and Miss Edwards.

There is no convincing evidence that the king was present, or that he attended any subsequent performance of Messiah; the first reference to the practice of standing appears in a letter dated 1756, three years prior to Handel's death.

[55][56] London's initially cool reception of Messiah led Handel to reduce the season's planned six performances to three, and not to present the work at all in 1744—to the considerable annoyance of Jennens, whose relations with the composer temporarily soured.

[58] The 1749 revival at Covent Garden, under the proper title of Messiah, saw the appearance of two female soloists who were henceforth closely associated with Handel's music: Giulia Frasi and Caterina Galli.

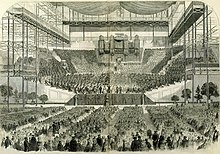

[72] In 1788 Hiller presented a performance of his revision with a choir of 259 and an orchestra of 87 strings, 10 bassoons, 11 oboes, 8 flutes, 8 horns, 4 clarinets, 4 trombones, 7 trumpets, timpani, harpsichord and organ.

In Leipzig in 1856, the musicologist Friedrich Chrysander and the literary historian Georg Gottfried Gervinus founded the Deutsche Händel-Gesellschaft with the aim of publishing authentic editions of all Handel's works.

However, after the heyday of Victorian choral societies, he noted a "rapid and violent reaction against monumental performances ... an appeal from several quarters that Handel should be played and heard as in the days between 1700 and 1750".

[98] In 1950 John Tobin conducted a performance of Messiah in St Paul's Cathedral with the orchestral forces specified by the composer, a choir of 60, a countertenor alto soloist, and modest attempts at vocal elaboration of the printed notes, in the manner of Handel's day.

[99] The Prout version sung with many voices remained popular with British choral societies, but at the same time increasingly frequent performances were given by small professional ensembles in suitably sized venues, using authentic scoring.

In the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, David Scott writes, "the edition at first aroused suspicion on account of its attempts in several directions to break the crust of convention surrounding the work in the British Isles.

[112] In "Glory to God", Handel marked the entry of the trumpets as da lontano e un poco piano, meaning "quietly, from afar"; his original intention had been to place the brass offstage (in disparte) at this point, to highlight the effect of distance.

[31][113] In this initial appearance the trumpets lack the expected drum accompaniment, "a deliberate withholding of effect, leaving something in reserve for Parts II and III" according to Luckett.

As the oratorio moves forward with various shifts in key to reflect changes in mood, D major emerges at significant points, primarily the "trumpet" movements with their uplifting messages.

[43] A change of key to E major leads to the first prophecy, delivered by the tenor whose vocal line in the opening recitative "Comfort ye" is entirely independent of the strings accompaniment.

The music proceeds through various key changes as the prophecies unfold, culminating in the G major chorus "For unto us a child is born", in which the choral exclamations (which include an ascending fourth in "the Mighty God") are imposed on material drawn from Handel's Italian cantata Nò, di voi non-vo'fidarmi.

[118] The pastoral interlude that follows begins with the short instrumental movement, the Pifa, which takes its name from the shepherd-bagpipers, or pifferari, who played their pipes in the streets of Rome at Christmas time.

[43] The appropriateness of the Italian source material for the setting of the solemn concluding chorus "His yoke is easy" has been questioned by the music scholar Sedley Taylor, who calls it "a piece of word-painting ... grievously out of place", though he concedes that the four-part choral conclusion is a stroke of genius that combines beauty with dignity.

[47] The declamatory opening chorus "Behold the Lamb of God", in fugal form, is followed by the alto solo "He was despised" in E-flat major, the longest single item in the oratorio, in which some phrases are sung unaccompanied to emphasise Christ's abandonment.

[122] The subsequent series of mainly short choral movements cover Christ's Passion, Crucifixion, Death and Resurrection, at first in F minor, with a brief F major respite in "All we like sheep".

[47] After the celebratory tone of Christ's reception into heaven, marked by the choir's D major acclamation "Let all the angels of God worship him", the "Whitsun" section proceeds through a series of contrasting moods—serene and pastoral in "How beautiful are the feet", theatrically operatic in "Why do the nations so furiously rage"—towards the Part II culmination of Hallelujah.

[129] It is followed by a quiet chorus that leads to the bass's declamation in D major: "Behold, I tell you a mystery", then the long aria "The trumpet shall sound", marked pomposo ma non-allegro ("dignified but not fast").

[90] In 1954 the first recording based on Handel's original scoring was conducted by Hermann Scherchen for Nixa,[n 12] quickly followed by a version, judged scholarly at the time, under Sir Adrian Boult for Decca.

[109] In addition to Mozart's well-known reorchestration, arrangements for larger orchestral forces exist by Goossens and Andrew Davis; both have been recorded at least once, on the RCA[149] and Chandos[150] labels respectively.