Thermocline

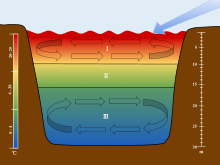

A thermocline (also known as the thermal layer or the metalimnion in lakes) is a distinct layer based on temperature within a large body of fluid (e.g. water, as in an ocean or lake; or air, e.g. an atmosphere) with a high gradient of distinct temperature differences associated with depth.

In the ocean, the thermocline divides the upper mixed layer from the calm deep water below.

Factors that affect the depth and thickness of a thermocline include seasonal weather variations, latitude, and local environmental conditions, such as tides and currents.

Waves mix the water near the surface layer and distribute heat to deeper water such that the temperature may be relatively uniform in the upper 100 metres (330 ft), depending on wave strength and the existence of surface turbulence caused by currents.

As saline water does not freeze until it reaches −2.3 °C (27.9 °F) (colder as depth and pressure increase) the temperature well below the surface is usually not far from zero degrees.

These same schlieren can be observed when hot air rises off the tarmac at airports or desert roads and is the cause of mirages.

A permanent thermocline is one that is not affected by season and lies below the yearly mixed layer maximum depth.

As winter approaches, the temperature of the surface water will drop as nighttime cooling dominates heat transfer.

This enriching of surface nutrients may produce blooms of phytoplankton, making these areas productive.

Temperature generally decreases with altitude, but the heat from the day's exposure to sun is released at night, which can create a warm region at ground with colder air above.

The scales are used to associate each section of the stratification to their corresponding depths and temperatures. The arrow is used to show the movement of wind over the surface of the water, which initiates the turnover in the epilimnion and hypolimnion.