Metallurgy in pre-Columbian America

[2] The metal would have been found in nature without the need for smelting, and shaped into the desired form using hot and cold hammering without chemical alteration or alloying.

[4] South American metal working seems to have developed in the Andean region of modern Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, and Argentina with gold and native copper being hammered and shaped into intricate objects, particularly ornaments.

[5][6] Ice core studies in Bolivia suggest copper smelting may have begun as early as 700 BC, over 2700 years ago.

[8] Further evidence for this type of metal work comes from the sites at Waywaka (near Andahuaylas in southern Peru), Chavín and Kotosh,[9] and it seems to have been spread throughout Andean societies by the Early horizon (1000–200 BC).

Though also functional objects were produced, even in the metallurgically advanced Andean cultures of the Inca era stone tools were never completely replaced by bronze items in everyday life.

Smelting was done in adobe brick furnaces with at least three blow pipes to provide the air flow needed to reach the high temperatures.

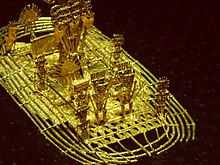

Analysis of a Moche statue composed of numerous thin metal layers revealed complex plating and gilding involving a combination of immersion in acidic solutions and the application of extreme heat.

[15] Some functional objects were fashioned, but they were elaborately decorated and often found in high-status burials, seemingly still used more for symbolic than for practical purposes.

[18] Coastal communities of Atacama Desert, as exemplified by those near Tocopilla, produced their own metal objects for practical use in the 900–1400 CE period.

[20] Muisca goldworking, from modern Colombia, made a wide variety of small ornamental and religious objects from about 600 CE onwards.

[citation needed] At Machu Picchu and other sites, metal was used for bolas, plumb bobs, chisels, gravers, pry bars, tweezers, needles, plates, fish hooks, spatulas, ladles, knives (tumi), bells, breastplates, lime spoons, mace heads, ear spools, bowls, cloak pins (tupus), axes, and foot plough adzes.

[22] It has been claimed that the Inca Empire expanded into Diaguita lands in what is now north-central Chile because of its mineral wealth, but that view is rejected by some scholars.

[23] Further, an additional possibility is that the Incas invaded the relatively well-populated Eastern Diaguita valleys (present-day Argentina) to obtain labor to send to Chilean mining districts.

[26] Among the Mapuche people of central and south-central Chile, gold had an important cultural significance that predates Inca contact.

There is considerable evidence that this technology, its raw materials and end products were widely traded in Mesoamerica throughout the Formative era (2000–200 BCE).

[31] Lumps of iron pyrite, magnetite, and other materials were mostly shaped into mirrors, pendants, medallions, and headdress ornaments for decorative and ceremonial effect.

By 700–800 CE, small metal sculptures were common and an extensive range of gold and tumbaga ornaments constituted the usual regalia of persons of high status in Panama and Costa Rica.

Most Caribbean metallurgy has been dated to between 1200 and 1500 CE and consists of simple, small pieces such as sheets, pendants, beads and bells.

[40] Exchange of ideas and goods with peoples from the Ecuador and Colombia region (likely via a maritime route) seems to have fueled early interest and development.

[40] By this time, copper alloys were being explored by West Mexican metallurgists, partly because the different mechanical properties were needed to fashion specific artifacts, particularly axe-monies – further evidence for contact with the Andean region.

[41] In the Tarascan Empire, copper and bronze was used for chisels, punches, awls, tweezers, needles, axes, discs, and breastplates.

This labor-intensive process might have been eased by building a fire on top of the deposit, then quickly dousing the hot rock with water fracturing the mental.

[citation needed] The copper could then be cold-hammered into shape, which would make it brittle, or hammered and heated in an annealing process to avoid this.

Great Lake artifacts found in the Eastern Woodlands of North America seem to indicate there were widespread trading networks by 1000 BC.

This site however was dated to around 4,000 years ago, a time of cooler climate when the boreal forest's treeline moved much further south.

However, Lake Superior, as a unique source of copper for over 6,000 years has recently come into some criticism, particularly since other deposits have been found that other archiac cultures mined on a much smaller scale.

Among 19th century Muscogee Creeks, a group of copper plates carried along the Trail of Tears are regarded as some of the tribe's most sacred items.

[57] Native ironwork in the Northwest Coast has been found in places like the Ozette Indian Village Archeological Site, where iron chisels and knives were discovered.

These artifacts seem to have been crafted around 1613, based on the dendrochronological analysis of associated pieces of wood in the site, and were made out of drift iron from Asian (specifically Japanese) shipwrecks, which were swept by the Kuroshio Current towards the coast of North America.

[58] The wrecking of Japanese and Chinese vessels in the North Pacific basin was fairly common, and the iron tools and weaponry they carried provided the necessary materials for the development of the local ironwork traditions among the Northwestern Pacific Coast peoples,[59] although there were also other sources of iron, like that from meteorites, which was occasionally worked using stone anvils.