Method ringing

This creates a form of bell music which is continually changing, but which cannot be discerned as a conventional melody.

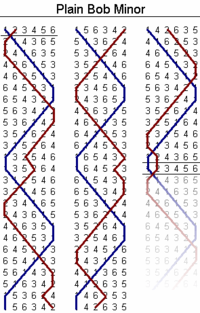

Ringers typically learn a particular method by studying its "blue line", a diagram which shows its structure.

The underlying mathematical basis of method ringing is intimately linked to group theory.

The first method, Grandsire, was designed around 1650, probably by Robert Roan who became master of the College Youths change ringing society in 1652.

The practice originated in England and remains most popular there today; in addition to bells in church towers, it is also often performed on handbells.

Grandsire, the oldest change ringing method, is based on a simple deviation to the plain hunt when the treble (bell No.1) is first in the sequence or it is said to "lead".

After this, the bells immediately return to the plain hunt pattern until the next treble lead.

This enables the other ringers to produce large numbers of unique changes without memorising huge quantities of data, without any written prompts.

Ringers typically start with rounds and then begin to vary the bells' order, moving on to a series of distinct rows.

Plain hunt is the simplest way of creating bell permutations, or changes.

Since permutations are involved, it is natural that for some people the ultimate theoretical goal of change ringing is to ring the bells in every possible permutation; this is called an extent (in the past this was sometimes referred to as a full peal).

Naturally, then, except in towers with only a few bells, ringers typically can only ring a subset of the available permutations.

But the key stricture of an extent, uniqueness (any row may only be rung once), is considered essential.

But once we limit ourselves to neighbour-swaps and to starting and ending with rounds, only 10,792 possible extents remain.

[4] It is to navigate this complex terrain that various methods have been developed; they allow the ringers to plot their course ahead of time without needing to memorize it all (an impossible task) or to read it off a numbingly repetitive list of numbers.

It is common practice in diagrams to draw a line under the lead end to assist in understanding the method.

In principles (where the treble does the same work as other bells and is affected by calls) the definition of a lead can become more complex.

These variations usually last only one change, but cause two or more ringers to swap their paths, whereupon they continue with the normal pattern.

By introducing such calls appropriately, repetition can be avoided, with the peal remaining true over a large number of changes.

As well as writing out the changes longhand (as in the accompanying illustration of Plain Bob Minor) there is a shorthand called Place Notation.

The odd-bell stage names refer to the number of possible swaps that can be made from row to row; in caters and cinques can be seen the French numbers quatre and cinq while the stage name for three-bell ringing is indeed "singles".

So likewise with caters, usually rung on ten bells, and other higher odd-bell stages.

Put together, this system gives method names sound that is evocative, musical, and quaint: Kent Treble Bob Major, Grandsire Caters, Erin Triples, Chartres Delight Royal, Percy's Tea Strainer Treble Place Major, Titanic Cinques and so forth.

This number derives from the great 17th-century quest to ring a full extent on seven bells; 7 factorial is 5,040.

Sturdier bell frames and more clearly understood methods make the task easier today, but a peal still needs about 3 hours of labor and concentration.

[citation needed] Most ringers follow the definition of a peal as regulated by the Central Council.