Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower

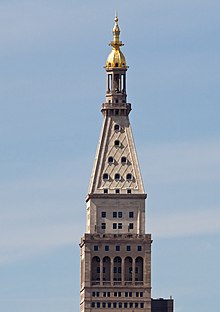

Inspired by St Mark's Campanile, the tower features four clock faces, four bells, and lighted beacons at its top, and was the tallest building in the world until 1913.

[22] Like the facades of many early skyscrapers, the tower's exterior was divided into three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column—namely a base, shaft, and capital—in both its original and renovated forms.

[8][21] During the 1964 renovation, plain limestone was used to cover the tower and the east wing, replacing LeBrun's old Renaissance Revival details with a streamlined, modern look.

[15] The lowest portion of the facade along Madison Avenue and 24th Street contains a 5-foot-tall (1.5 m) water table made of granite, which wraps around to the east wing.

[42] When built, the tower section featured granite floors and metal interior furnishings, though there was very little wood trim, unlike other contemporary structures.

[45] During the 1960s renovation, the tower was fitted with more modern furnishings such as air conditioning, acoustic ceiling tiles, and automatic elevators, to match the new eastern wing.

[51] It extends east to Park Avenue South, covering nearly the entire block,[52][53] and originally had nearly 1.2 million square feet (110,000 m2) of interior space.

[54] In the early 2020s, the 10th through 14th stories were demolished (accounting for nearly half the building's height),[51] and an 18-story glass-faced office tower was built over the roof of the ninth floor.

[56] At the southeastern corner, on the basement level, there is a direct entrance to the downtown platform of the New York City Subway's 23rd Street station, served by the 6 and <6> trains.

It consists of floors and walls made of white marble and darker-marble accents, as well as a sheet rock ceiling with lighting panels, and stainless-steel doors and trim.

[52] A replica of the original home office's board room was built on the 11th floor of the east wing, and featured mahogany wainscoting, a coffered ceiling, and leather covering the walls.

[56][57] The annex's anchor tenant, IBM, installed a wave-shaped light fixture in the lobby, as well as a blue bar and a technology center on the second floor.

There was also a recreational space on the roof of the home office's 23rd Street portion,[81] and through the larger complex's extensive system of kitchens and dining rooms,[g] the company offered free lunch to every employee between 1908 and 1994.

[83] Before the home office at Madison Square was completed, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (now MetLife) had been headquartered at three buildings in Lower Manhattan,[24][84][85] all of which have been demolished.

According to architectural writer Kenneth Gibbs, these buildings allowed each individual company to instill "not only its name but also a favorable impression of its operations" in the general public.

[89][91] Furthermore, life insurance companies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries generally built massive buildings to fit their large clerical and records-keeping staff.

[24][86] Metropolitan Life occupied the second through fifth floors for its own use, but soon afterward expanded to the sixth and ninth stories, while filling the ground-story storefront spaces.

[98] Metropolitan Life bought the corner of Fourth Avenue and 24th Street in 1902–1903 and constructed the next portion of the home office on the Lyceum Theatre and Academy of Design sites.

[75] A plot on the north side of 24th Street, measuring 75 by 100 feet (23 by 30 m), was developed from 1903 to 1905 as the first Metropolitan Annex, a 16-story printing plant building faced in Tuckahoe marble.

[114] By the late 1920s, the clock tower, home office, and LeBrun's and Waid's northern annexes were becoming too small to house the continuously growing activities of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

[15][53] In 1952, Morgan and Meroni filed plans with the New York City Department of Buildings for a completely new structure on the site of the existing home offices.

[64] The tower, the sole structure on the block that remained from the early 20th century, was renovated starting in 1961 to harmonize the design with Morgan and Meroni's east wing.

[56] The glass addition and the renovation of One Madison Avenue was developed by SL Green, Hines, and the National Pension Service of Korea at a cost of $2.3 billion.

[137][138] Other initial tenants of the rebuilt building included Coinbase,[139] Flutter Entertainment,[140] Franklin Templeton Investments,[141] Palo Alto Networks,[142] and a steakhouse and terrace operated by Daniel Boulud.

[145] By that September, the One Madison Avenue annex was nearly complete, and the building had received a temporary certificate of occupancy;[51][146] at the time, the space in the glass addition had been nearly fully leased.

[99] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission described the original home office's design as doing "much to establish Metropolitan Life in the eyes and the mind of the public.

"[24] In a company history book written shortly after the building's completion, Metropolitan Life had characterized the structure as "the most beautiful home office in the world".

[40] On December 11, 1984, to celebrate the building's 75th anniversary, the United States Postal Service issued a pictorial cancellation that depicted the Metropolitan Life Tower, which was available only on that day.

[60] Wachs also wrote that, "compared with its showy predecessor, One Madison Avenue is an introvert" because the annex's trusses and terraces could not be seen from ground level, and because the glass curtain walls were not fully transparent due to the presence of window screens.

[158][159] The Metropolitan Life Home Office Complex, which includes the tower and the adjacent North Building, was added to the National Register on January 19, 1996.