Fengu people

After some years of oppression by the Gcaleka Xhosa (who called the Fengu people their "dogs")[citation needed]in the 1820s, they formed an alliance with the Cape government in 1835 and Sir Benjamin d'Urban invited 17,000 to settle on the banks of the Great Fish River in the region that later became known as the Ciskei.

[3] Some scholars, including Timothy Stapleton and Alan Webster, argue that the traditional narrative of the Fengu people as refugees of the Mfecane is in fact a lie constructed by colonial missionaries and administrators.

[11] The educated Fengu went as far as Port Elizabeth, where they worked at the harbour and established urban communities in Cape Town, where they also continued practising as Christians.

Cecil John Rhodes brought a group of Fengu fighters (who had fought on the side of the British) and were known as "the Cape Boys" in 1896.

Prime Minister John Molteno, who held a very high opinion of Bikitsha, appointed him as a leader of the Cape forces (together with Chief Magistrate Charles Griffith) in the 9th Frontier War in 1877, where he swiftly won a string of brilliant victories against the Gcaleka.

Throughout the 9th Frontier war, Bikitsha and his location were a focal point for the Gcaleka armies attacks and came under immense military pressure.

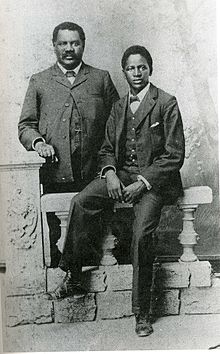

He founded the Transkei General Council, and served as a juror and commissioner for the Cape Colony in later life[14] As Fengu history switched from military defense to political struggle, so the great Fengu politician and activist John Tengo Jabavu rose in prominence after Bikitsha's military leadership ended.

The rivalry between the Fengu and the Gcaleka Xhosa, which had previously broken out into war, declined during the era of Jabavu's leadership, as greater unity was encouraged.

Rubusana's rise in the 1890s was through the new Gcaleka-dominated South African Native National Congress and their newspaper Izwi Labantu ("The Voice of the People") which was financed by Cecil Rhodes.

The rise of Xhosa institutions meant that Jabavu and the Fengu were no longer in a position to provide the only leadership in the Cape's Black community.

Over the next few decades, divisions persisted between Jabavu's movement Imbumba ("The Union") and Rubusana's South African Native National Congress.

Barring the brief revolt in 1877 and 1878, when the Gcaleka turned upon their Fengu neighbours, the British annexation of land east of the Kei River proceeded fitfully, but generally unimpeded.

It is assumed that the restructuring of these territories into the divisions of Butterworth, Idutywa, Centani, Nqamakwe, Tsomo and Willowvale dates from these times.

Originally farmers, the Fengu people had quickly built themselves schools, created and edited their own newspapers, and translated international literature into their language.

The reason that the Fengu people were able to adapt so effectively to changing circumstances (like the coming of capitalism and urbanisation) was because they lacked a fixed tribal social-structure and hierarchy (having presumably lost it in their earlier flight from the Zulu).

This state of social change and flexibility allowed them to quickly adjust to the European expansion, learn and adapt new techniques, and take advantage of the upheavals that followed.