Michael O'Flanagan

In later years he edited the 1837 Ordnance Survey letters and prepared sets for institutions and universities; in the 1930s he worked on a series of County Histories, and ten volumes were published by the time of his death.

He entered St Patrick's College, Maynooth in the autumn of 1894 where he had an excellent academic record, winning prizes in theology, scripture, canon law, Irish language, education, and natural science.

He returned to Ireland in 1905 and procured a trio of lace and craftworkers, Mary O'Flanagan Rose Egan and Kate Davoren, and set up a travelling industrial and cultural exhibition.

O'Flanagan, after consultation with Hyde in Dublin, issued a statement in the New York Times on 4 December 1911 disassociating the work of the Gaelic League from anything to do with William Butler Yeats, Lady Gregory or the Abbey players.

[30] O'Flanagan then delivered a passionate oration to a select group of Irish Volunteers and nationalists at the reception of O'Donovan Rossa's remains to the lying-in-state in Dublin City Hall.

The following day O'Flanagan accompanied the O'Donovan Rossa family to Glasnevin Cemetery where he recited the final prayers in Irish by the graveside standing beside Patrick Pearse who then made his iconic speech.

"Chaired by Canon Doorley, later bishop of Elphin, the meeting was packed with official personages such as the crown solicitor for Sligo T. H. Williams and the RIC district inspector, O'Sullivan.

In January 1916 he took the train to Cork where he spoke to a monster crowd at an anti-conscription meeting chaired by Thomás MacCurtáin – later assassinated by Crown forces – and policed by Terence MacSwiney who would die in 1920 after a 74-day hunger strike.

[38] Noting these preparations Bishop Coyne issued a warning by letter to O'Flanagan on 21 January 1917, beginning "In view of the present political unrest in part of the country, and to prevent any misunderstanding in the future, I would like to call your attention to the following statute on the national Synod of Maynooth (p. 121, no.

[8] They were joined by workers from Dublin and other parts, such as Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, Larry Nugent, Rory O'Connor, Darrell Figgis, William O'Brien, Kevin O'Shiel, Joseph McGrath and Count Plunkett's daughter Geraldine with her husband Thomas Dillon.

[8] On 19 April 1917 Count Plunkett chaired a Convention of advanced nationalists at the Mansion House in Dublin in an attempt to seek common ground in the aftermath of the North Roscommon election victory.

[41] A convention was held at the end of October 1917, where the Easter Rising veterans and other supporting groups merged with Arthur Griffith's older organisation and adopted the name of Sinn Féin.

[43] In response to this wave of protest, Lord French's German Plot was set in motion, when old letters belonging to Sir Roger Casement were resurrected and used as flimsy propaganda.

[6] When the polling took place in December, Sinn Féin swept the boards, completing the process begun in North Roscommon, decimating the Irish Parliamentary party by taking 73 of the 105 seats available.

O'Flanagan is standing with Count Plunkett and Arthur Griffith, accompanied by Éamon de Valera, Lawrence O'Neill the Lord Mayor of Dublin, and possibly W. T. Cosgrave, on the steps of the Mansion House.

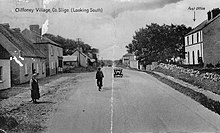

[28] The local Volunteers, many of whom were friends of O'Flanagan, attacked a nine-man RIC patrol from Cliffoney barracks and shot four dead including the sergeant, close to Ahamlish graveyard.

[21] Bloody Sunday took place on 21 November when thirteen members of the Crown forces, sixteen civilians and three republican prisoners, including Dick McKee and Conor Clune, were killed.

"[42] De Valera used O'Flanagan to hold informal talks with Lloyd George in early January, where they discovered that Dominion status for Southern Ireland was the most that the British were prepared to offer.

[59] In late January 1921, O'Flanagan and judge James O'Connor met informally in London with Sir Edward Carson to discuss a peaceful solution to the conflict, but without success.

[62] O'Flanagan was touring the east coast giving lectures and getting plenty of newspaper coverage in his mission "to help in raising the second external bond certificate loan of Dáil Éireann," when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed on 6 December 1921.

Reformed in 1923 by de Valera, the third Sinn Féin "was a coalition of different elements, and while it no longer included any non-republicans it remained an uneasy combination of extremists and (relative) moderates, of ideologues and politicians, of fundamentalists and realists.

[69] In April O'Flanagan was suspended from clerical duties by Bishop Coyne and forbidden to say mass, because of his outspoken nationalist activities and the anti-clerical speeches he had made in America and for delivering "dis-edifying harangues to excited mobs at five places in the diocese of Elphin.

[72] De Valera left to found Fianna Fáil, and the majority of the more talented members of Sinn Féin followed him, leaving behind the rump Sean Lemass referred to as a "galaxy of cranks.

Having no clerical income while he was suspended, O'Flanagan travelled to the United States for a number of months each year, giving lectures on his historical work and the Irish political situation.

[75] By the late 1920s, when he had no income from the Church, he was selling his goggles by mail order from his home in Bray, County Wicklow, advertising them in the Catholic Bulletin and on his lecture tours in the USA.

In his 1927 lecture, Church and Politics, O'Flanagan describes how he funded the massive undertaking using a donation from supporters in America, and mentions the vast amounts of documents destroyed in the Four Courts bombardments.

In the 1930s he undertook further historical work when he was commissioned by the government to write a series of county histories in the Irish language for use in National schools; five of the ten parts were published in his lifetime.

On 3 December 1936 he chaired a meeting in the engineers hall in Dublin, where George Gilmore, recently back from Spain, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and Frank Ryan presented alternate views to the raging pro-Franco propaganda.

[85]After a short illness in the nursing home at 7 Mount Street Crescent, Dublin, O'Flanagan died of stomach cancer on at 4.30 pm on Friday 7 August 1942, within a few days of his sixty-sixth birthday.

O'Flanagan was described in a memoir by Sean O'Casey as "An unselfish man, a brilliant speaker, with a dangerous need of more respect for bishops dressed in a little brief authority; a priest spoiled by too many good qualities.