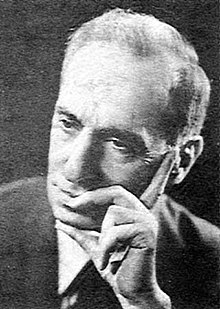

Michel Aflaq

Born into a middle-class family in Damascus, Syria, Aflaq studied at the Sorbonne, where he met his future political companion Salah al-Din al-Bitar.

During the mid-to-late 1950s the party began developing relations with Gamal Abdel Nasser, the President of Egypt, which eventually led to the establishment of the United Arab Republic (UAR).

During his stay, Aflaq was influenced by the works of Henri Bergson and met his longtime collaborator Salah al-Din al-Bitar, a fellow Syrian nationalist.

[5] In 1941 the Syrian Committee to Help Iraq was established to support the Iraqi Government led by Rashid Ali al-Gaylani against the British invasion during the Anglo–Iraqi War.

Under the constitution adopted at the congress, this made him effective leader of the party, with sweeping powers within the organisation; al-Bitar was elected Secretary General of the National Command.

[14] The merger would prove problematic; several members of the al-Arsuzi-led Ba'ath Party were more left-leaning, and would become, later in Aflaq's tenure as leader, highly critical of his leadership.

Aflaq called for al-Quwatli's resignation, and wrote several al-Ba'ath articles criticising his presidency and his prime minister, Jamil Mardam Bey.

[17] Aflaq at first extended his support to the new government, believing that he and the Ba'ath Party could collaborate with Shishakli because they shared the same Arab nationalist sentiments.

[28] The plotters' first order was to establish the National Council of the Revolutionary Command (NCRC), consisting entirely of Ba'athists and Nasserists, and controlled by military personnel rather than civilians from the very beginning.

[30] Nasser started launching bitter propaganda attacks against the party; Aflaq was dismissed as an ineffectual theorist who was mocked as a puppet "Roman emperor" and accused of being a "Cypriot Christian".

After taking power, the Military Committee looked for theoretical guidance, but instead of going to Aflaq to solve problems (which was usual before), they contacted the party's Marxist faction led by Hammud al-Shufi.

[33] At the Syrian Ba'athist Regional Congress, the Military Committee "proved" that it was rebelling equally against Aflaq and the traditional leadership, as against their moderate social and economic policies.

At the Sixth National Congress held in October 1963, Aflaq was barely able to hold on to his post as Secretary General – the Marxist factions led by al-Shufi and Ali Salih al-Sa'di, in Syria and Iraq respectively, were the majority group.

Another problem facing Aflaq was that several of his colleagues were not elected to party office; for instance, al-Bitar was not reelected to a seat in the National Command.

While the Military Committee was in fact taking control over the Ba'ath Party from the civilian leadership, they were sensitive to such criticism, and stated, in an ideological pamphlet, that civilian-military symbiosis was of major importance if socialist reconstruction was to be achieved.

This was not greeted warmly by the majority of Iraqi military officers and Ba'athists – the idea that a Christian was to rule over a Muslim country was considered "insensitive".

To counter this, the Military Committee befriended a staunchly anti-Aflaq civilian faction calling themselves the "Regionalists" – this group had not dissolved their party organisations as ordered by Aflaq in the 1950s.

[42] On 23 February a coup d'état led by Jadid and Hafez al-Assad overthrew the Syrian Government and the Ba'ath Party leadership.

[44] When the new rulers launched a purge in August that year, Aflaq managed to make his escape, with the help of Nasim Al Safarjalani and Malek Bashour, both closely trusted friends and colleagues, and hence was able to flee to Beirut, Lebanon,[45] and later to Brazil.

[47] In February 1966 at the Ninth National Congress, held after the coup which ousted the pro-Aflaq faction, the Iraqi delegation split with the Syrian Ba'athists.

The tomb, widely regarded as a work of great artistic merit, designed by Iraqi architect Chadagee, was located on the western grounds of the Ba'ath Party Pan-Arab Headquarters, at the intersection of Al-Kindi street and the Qadisiyyah Expressway overpass.

Dictatorship is a precarious, unsuitable and self-contradictory system which does not allow the consciousness of the people to grow.The Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party slogan "Unity, liberty, socialism" is the key tenet of Aflaq's and Ba'athist thought.

[70] For more than 2 decades, Michel Aflaq's essay compilation titled Fi Sabil al-Ba'ath (trans: "The Road to Renaissance") was the primary ideological book of the Ba'ath party.

They garnered significant criticism from devout Muslims, who viewed the suggestion that the Arab genius was the flowering of Islam rather than the revelation of God as offensive.

Being influenced by a mixture of radical Hobbesian and Marxist ideas, Michel Aflaq viewed religion as the "opiate of the masses", which subverted efforts for the advancement of a socialist revolution.

In 1956, Aflaq asserted that religion was a tool used by the elites of the traditional social order to maintain a corrupt system which facilitated the oppression and exploitation of the weaker classes of the society.

He also claimed that religion was regularly exploited by oppressive elites to sedate the people and prevent the outbreak of mass revolutions against the prevailing socio-political order.

As Kanan Makiya, the author of Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq, notes: for "Aflaq, reality is confined to the inner world of the party."

In contrast to other philosophers, such as Karl Marx or John Locke, Aflaq's ideological view of the world makes no clear stand on the materialistic or socioeconomic behavior of humanity.

"[81] He has been accused of seeking help from other people instead of fulfilling his goal by himself or with others he led; Aflaq collaborated with Gamal Abdel Nasser, Abd al-Karim Qasim and Abdul Rahman Arif in 1958, to Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr and Ali Salih al-Sadi in 1963 and finally in the 1970s to Saddam Hussein.